Do you know this man? Please contact his family!

“Do not think that because you are in the king’s house you alone of all the Jews will escape. For if you remain silent at this time, relief and deliverance for the Jews will arise from another place, but you and your father’s family will perish. And who knows but that you have come to royal position for such a time as this?” Esther 4:13 – 14 (NIV)

For Washington state residents:

Know Your Rights | NWIRP.org https://share.google/rBo8Gb7vA88qbIM2K

“But let me make it perfectly clear that in no way is suffering necessary to find meaning. I only insist that meaning is possible even in spite of suffering–provided, certainly, that the suffering is unavoidable. If it were avoidable, however, the meaningful thing to do would be to remove its cause, be it psychological, biological or political. To suffer unnecessarily is masochistic rather than heroic.”–Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist, Viktor E. Frankl, “Man’s Search For Meaning”

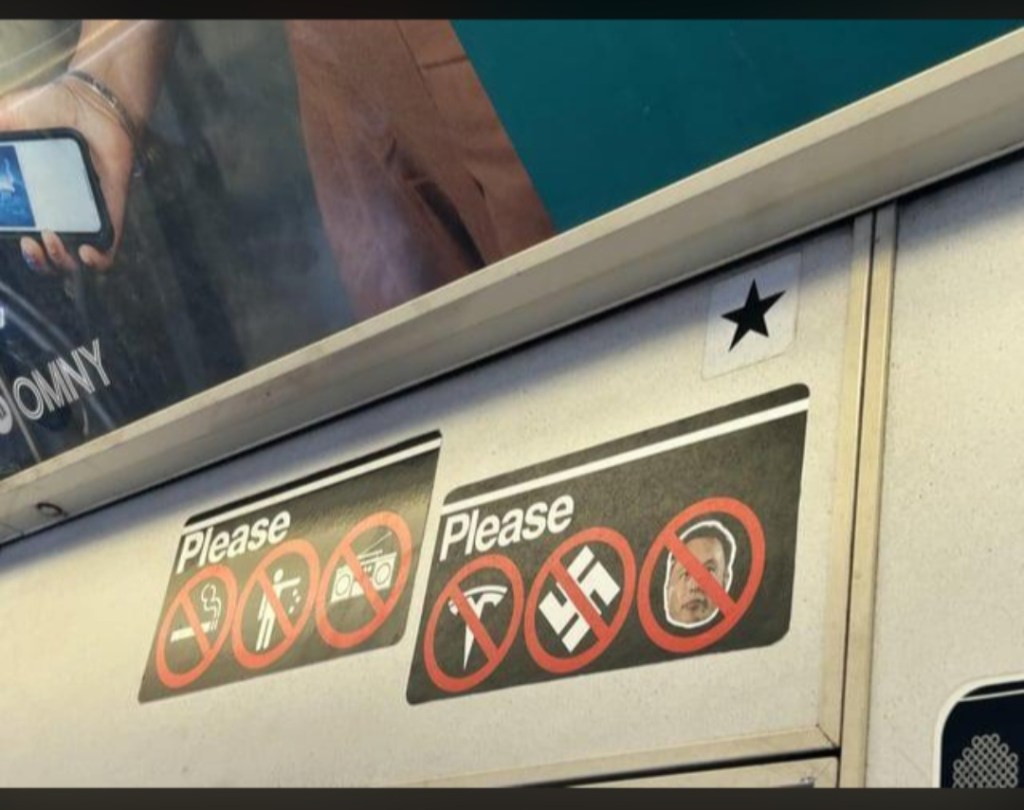

Forget impeachment, arrest Donald Trump and his evil lamprey Elon Musk now! American people are suffering unnecessarily from corruption and cruelty, and the cause are these two nazi barons. Stand up for our federal workers who are being illegally fired, and their families! Stand up for the human rights of trans people of ALL ages, and their families! Stand up for what is right and good for humanity!

“Thus the illusions some of us still held were destroyed one by one, and then, quite unexpectedly, most of us were overcome by a grim sense of humor. We knew that we had nothing to lose except our so ridiculously naked lives.”–Auschwitz survivor, Viktor E. Frankl; excerpt from “Man’s Search For Meaning”

Screenshots from the past 24 hours…

History repeats, fix your hearts!!

“I have observed this in my experience of slavery,–that whenever my condition was improved, instead of increasing my contentment, it only increased my desire to be free, and set me to thinking of plans to gain my freedom. I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason. He must be able to detect no inconsistencies in slavery; he must be made to feel that slavery is right; and he can be brought to that only when he ceases to be a man.”

[…]

“He told me I could go nowhere but that he could get me; and that, in the event of my running away, he should spare no pains in his efforts to catch me. He exhorted me to content myself, and be obedient. He told me, if I would be happy, I must lay out no plans for the future. He said, if I behaved myself properly, he would take care of me. Indeed, he advised me to complete thoughtlessness of the future, and taught me to depend solely upon him for happiness. He seemed to see fully the pressing necessity of setting aside my intellectual nature, in order to contentment in slavery. But in spite of him, and even in spite of myself, I continued to think, and to think about the injustice of my enslavement, and the means of escape.”

[…]

“I had a number of warm-hearted friends in Baltimore,–friends that I loved almost as I did my life,–and the thought of being separated from them forever was painful beyond expression. It is my opinion that thousands would escape from slavery, who now remain, but for the strong cords of affection that bind them to their friends. The thought of leaving my friends was decidedly the most painful thought with which I had to contend.”

[…]

“It was a most painful situation; and, to understand it, one must needs experience it, or imagine himself in similar circumstances. Let him be a fugitive slave in a strange land–a land given up to be the hunting-ground for slaveholders–whose inhabitants are legalized kidnappers–where he is every moment subjected to the terrible liability of being seized upon by his fellowmen, as the hideous crocodile seizes upon his prey!–I say, let him place himself in my situation–without home or friends–without money or credit–wanting shelter, and no one to give it–wanting bread, and no money to buy it,–and at the same time let him feel that he is pursued by merciless men-hunters, and in total darkness as to what to do, where to go, or where to stay,–perfectly helpless both as to the means of defence and means of escape,–in the midst of plenty, yet suffering the terrible gnawings of hunger,–in the midst of house, yet having no home,–among fellow-men, yet feeling as if in the midst of wild beasts, whose greediness to swallow up the trembling and half-famished fugitive is only equalled by that with which the monsters of the deep swallow up the helpless fish upon which they subsist,–I say, let him be placed in this most trying situation,–the situation in which I was placed,–then, and not till then, will he fully appreciate the hardships of, and know how to sympathize with, the toil-worn and whip-scarred fugitive slave.”

–From chapters 10 and 11 of “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself”

From Albert Camus’ “The Plague”, Part IV: a conversation between priest(Paneloux) and doctor(Rieux), shortly after witnessing the death of a child:

He heard a voice behind him. “Why was there that anger in your voice just now? What we’d been seeing was as unbearable to me as it was to you.”

Rieux turned toward Paneloux.

“I know. I’m sorry. But weariness is a kind of madness. And there are times when the only feeling I have is one of mad revolt.”

“I understand,”Paneloux said in a low voice. “That sort of thing is revolting because it passes our human understanding. But perhaps we should love what we cannot understand.”

Rieux straightened up slowly. He gazed at Paneloux, summoning to his gaze all the strength and fervor he could muster against his weariness. Then he shook his head.

“No, Father. I’ve a very different idea of love. And until my dying day I shall refuse to love a scheme of things in which children are put to torture.”

A shade of disquietude crossed the priest’s face. “Ah, Doctor,” he said sadly, “I’ve just realized what is meant by ‘grace.'”

Rieux had sunk back again on the bench. His lassitude had returned and from its depths he spoke, more gently:

“It’s something I haven’t got; that I know. But I’d rather not discuss that with you. We’re working side by side for something that unites us–beyond blasphemy and prayers. And it’s the only thing that matters.”

Paneloux sat down beside Rieux. It was obvious that he was deeply moved.

“Yes, yes,” he said, “you, too, are working for man’s salvation.”

Rieux tried to smile.

“Salvation’s much too big a word for me. I don’t aim so high. I’m concerned with man’s health; and for me his health comes first.”

Paneloux seemed to hesitate. “Doctor–” he began, then fell silent. Down his face, too, sweat was trickling. Murmuring: “Good-by for the present,” he rose. His eyes were moist. When he turned to go, Rieux, who had seemed lost in thought, suddenly rose and took a step toward him.

“Again, please forgive me. I can promise there won’t be another outburst of that kind.”

Paneloux held out his hand, saying regretfully:

“And yet–I haven’t convinced you!”

“What does it matter? What I hate is death and disease, as you well know. And whether you wish it or not, we’re allies, facing them and fighting them together.” Rieux was still holding Paneloux’s hand. “So you see”–but he refrained from meeting the priest’s eyes–“God Himself can’t part us now.”