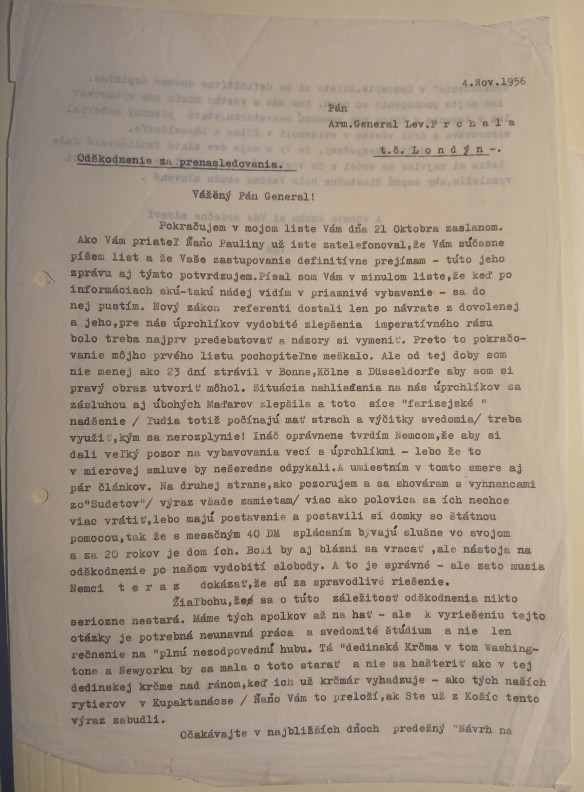

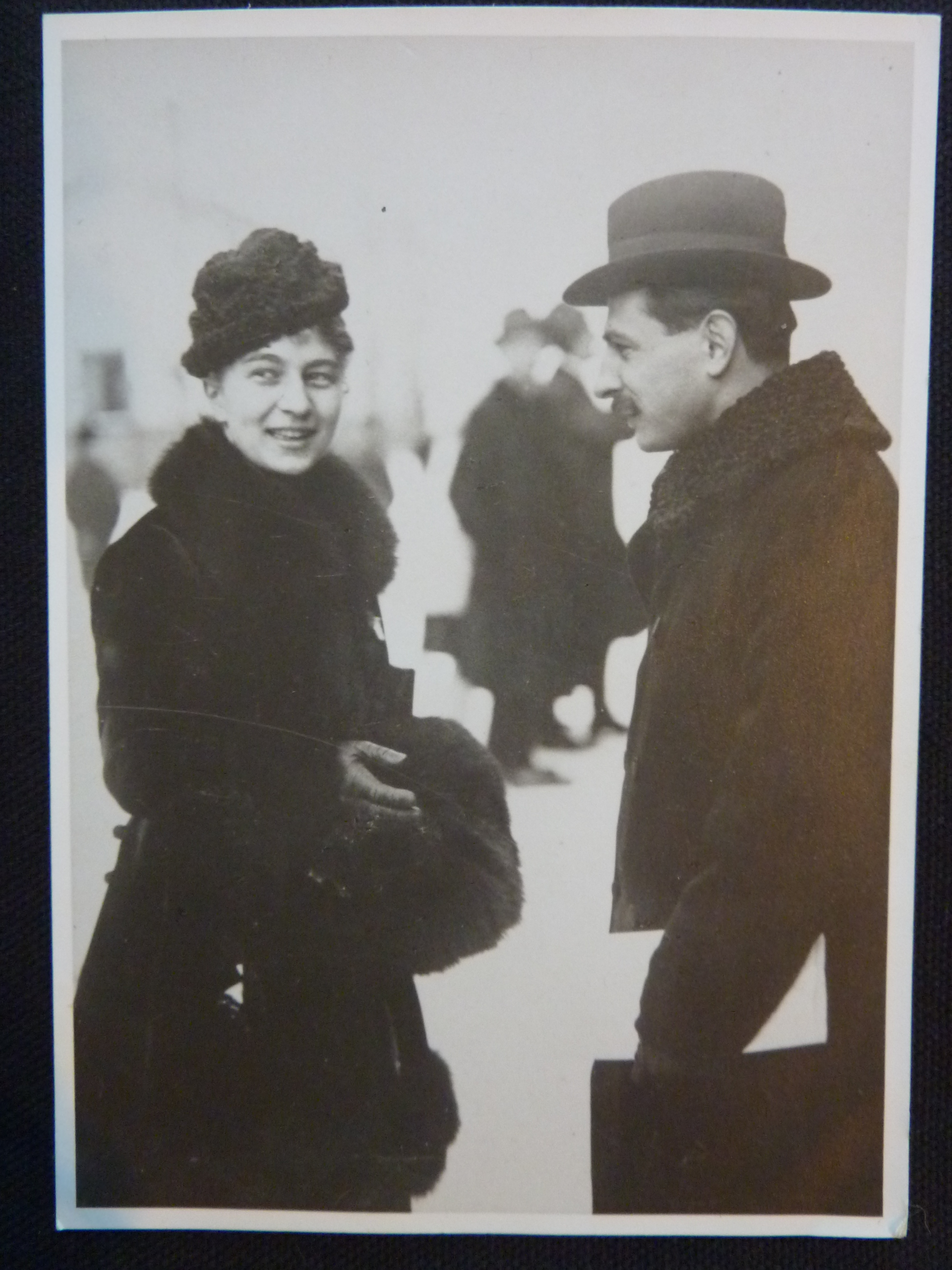

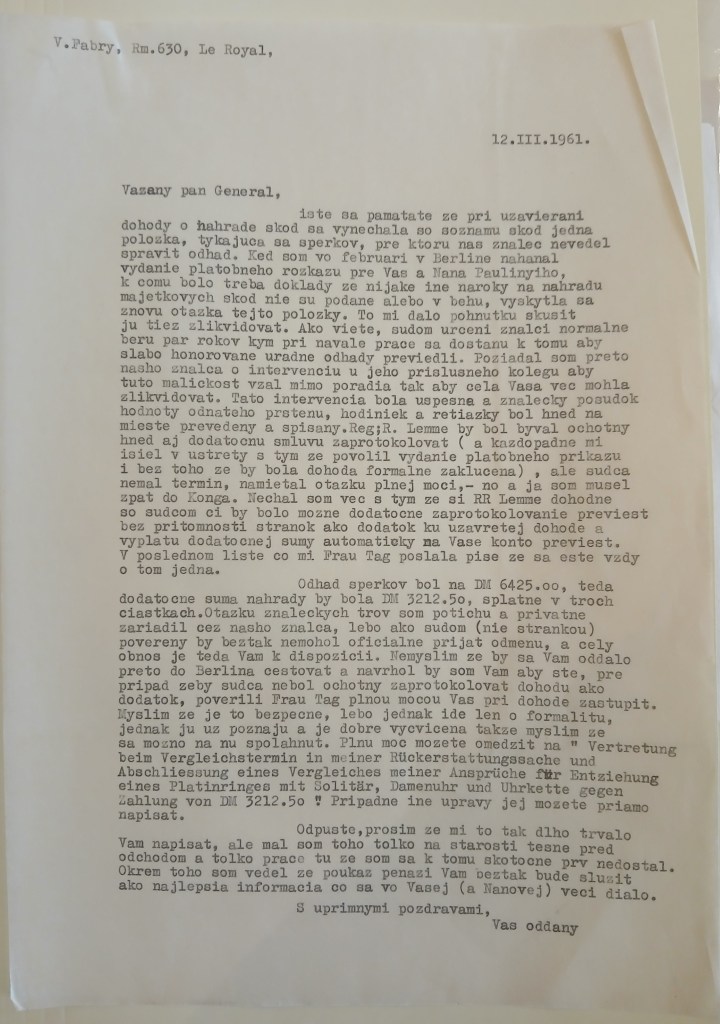

With great respect to Army General Lev Prchala and to our grandfather Dr. Pavel Fabry – Czechoslovakian heroes, defenders of democratic freedom, symbols of resistance against nazis and fascists! These are the last letters between them, from 1960, with related documents included. Translations will be added later. Pavel died of a heart attack in Berlin on 19 December 1960, he was 69. Vlado took over the remaining legal work from his father, somehow finding time for it while also working for the UN in the Congo. Vlado’s letter to the General is sent from Hotel Le Royal, Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), 12 March 1961. It brings tears to my eyes how much love they had for their friends, the personal sacrifices they were willing to make for each other – my cup runs over in their memory.

Thanks to Miroslav Kamenik for transcribing and translating all the handwritten letters here!

17.5.60

Vážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

byl bych Vám nesmírně vděčen, kdybyste mi alespoň několika slovy naznačil jak stojí záležitosti Vašich Londýnských klientů, resp. klientek, které mě svými dotazy stále bombardují.Také bych rád věděl, zda máte v úmyslu se se mnou v Německu viděti, poněvadž čas utíká a můj odlet do Mnichova se blíží. Počítám, že přiletím pravděpodobně 2 nebo 3 června a že se v Mnichově zdržím až týden. Pak bych Vám byl k dispozici a vše závisí z Vašich plánů, kdy a kde byste mě potřeboval.

Těším se na Vaši laskavou odpověď a jsem s ruky políbením milostivé paní a se srdečnými pozdravy

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I would be extremely grateful if you could give me at least a few words about the state of cases of your London clients, who are constantly bombarding me with their inquiries. I would also like to know whether you intend to see me in Germany, as time is running out and my departure for Munich is approaching. I expect to arrive probably on the 2nd or 3rd of June and to stay in Munich for up to a week. Then I would be at your disposal, and it all depends on your plans, when and where you would need me.

I look forward to your kind reply and I am with a kiss on the hand of your wife and with warm regards

Faithfully your

Prchala

20.5.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

dnes jsem obdržel letecký lístek London – Mnichov – London od Česko – Sud. Něm federálního výboru pro let dne 2. června 1960.

Poletím tedy ve čtvrtek dne 2. června do Mnichova a zdržím se tam asi týden. Zároveň jsem byl uvědoměn, že čestné pozvánky budou rozposlány v příštích dnech. Doufám, že pozvánku pro sebe a Vaši milostivou obdržíte co nejdříve.

A nyní mám k Vám, vzázcný příteli, jednu velikou prosbu. Abych zde měl pevný důkaz pro nutnost své jízdy do Německa, zašlete mně, prosím, telegram, v němž mě vyzýváte k schůzce v Německu. Dejž Bůh, aby taková schůzka se stala doopravdy možnou.

S ruky políbením velevážené milostivé paní a se srdečnými pozdravy jsem Váš oddaný,

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

today I received a London – Munich – London ticket from the Czech – SudetenGerman Federal Committee for the flight on June 2, 1960.

I will fly to Munich on Thursday, June 2, and will stay there for about a week. At the same time, I was informed that the honorary invitations will be sent out in the coming days. I hope that you will receive the invitation for yourself and your ladyship as soon as possible.

And now I have one great request for you, dear friend. So that I may have solid proof of the necessity of my journey to Germany, please send me a telegram in which you invite me to a meeting in Germany. God grant that such a meeting may actually become possible.

I am with a kiss on the hand of your wife and with warm regards

Faithfully your

Prchala

28.5.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

dovolte, abych Vám srdečně poděkoval za telegram, který jsem právě obdržel. Telegrafoval jsem ihned do Mnichova, aby Vám zaslali čestnou pozvánku, o kterou jsem žádal již před několika týdny. Vysvětluji si tuto chybu jedině tím, že Ing. Simon je zavalen prací a pevně doufám, že tento faux pas okamžitě napraví.

Těším se velice na setkání s Vámi a Vaší milostivou paní, které uctivě líbám ruku.

Srdečně Vás zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

P.S. Tatsachenbericht jsem odevzdal pí. S a pí. M. V Mnichově bydlím v hotelu „Esplanade“ naproti hl. nádraží.

Dear Doctor, my friend,

let me to thank you most cordially for the telegram I have just received. I immediately telegraphed to Munich to have the honorary invitation sent to you, which I had requested several weeks ago. I can only explain this mistake by saying that Ing. Simon is overwhelmed with work and I firmly hope that he will rectify this faux pas immediately.

I am very much looking forward to meeting you and your honorable wife, whose hand I respectfully kiss.

Yours sincerely

Prchala

P.S. I handed over the Tatsachenbericht to Mrs. S and Mrs. M. In Munich I live in the hotel “Esplanade” opposite the main station.

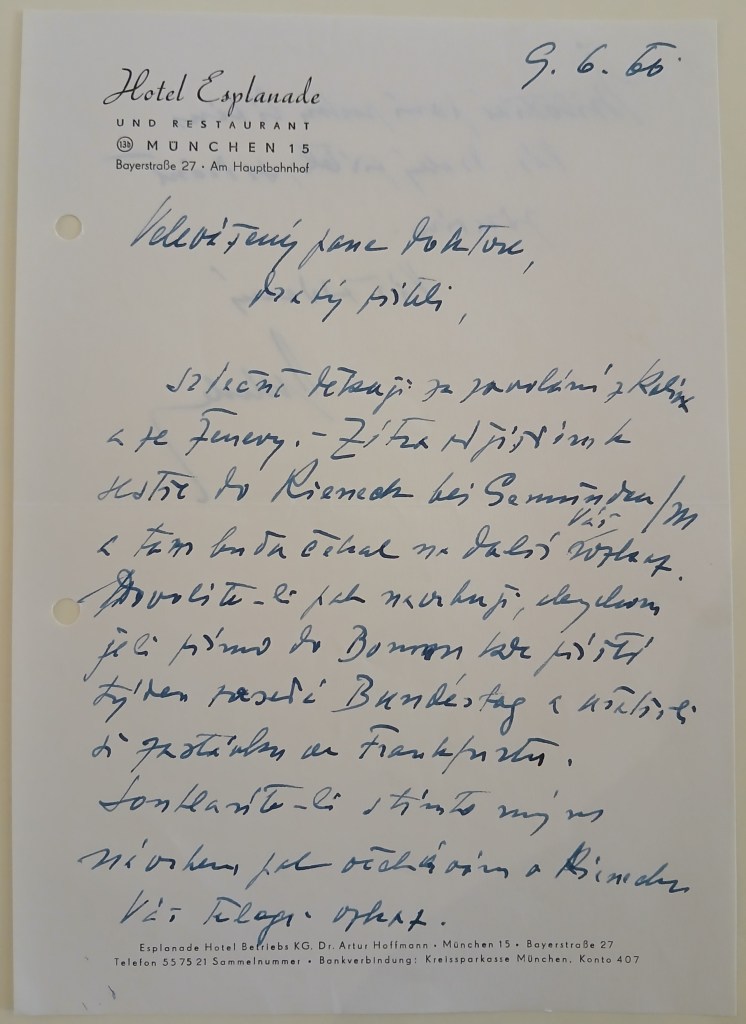

9.6.60, München, Hotel Esplanade

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

srdečně děkuji za zavolání z Kolína a ze Ženevy. Zítra odjíždím k sestře do Rieneck bei Gemünden / M a tam budu čekat na další Váš rozkaz. Dovolíte-li, pak navrhuji, abychom jeli přímo do Bonnu kde příští týden zasedá Bundestag a ušetřili si zastávku ve Frankfurtu. Souhlasíte-li s tímto mým návrhem, pak očekávám v Rienecku Váš telegr. vzkaz.

Milostivé paní ruku líbám,

Vás, drahý příteli, srdečně zdravím.

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

thank you very much for your call from Cologne and Geneva. Tomorrow I am leaving for my sister in Rieneck bei Gemünden / M and there I will await your further orders. If you allow me, I suggest that we go directly to Bonn where the Bundestag is in session next week and save ourselves a stopover in Frankfurt. If you agree with this proposal of mine, I am expecting your telegram in Rieneck.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

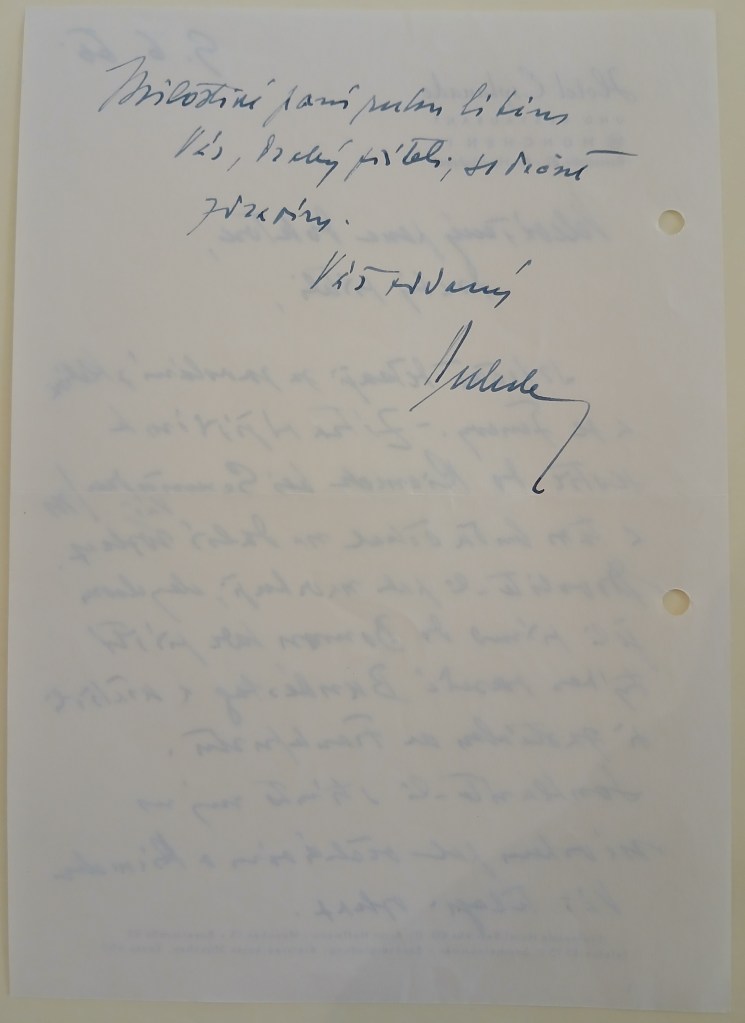

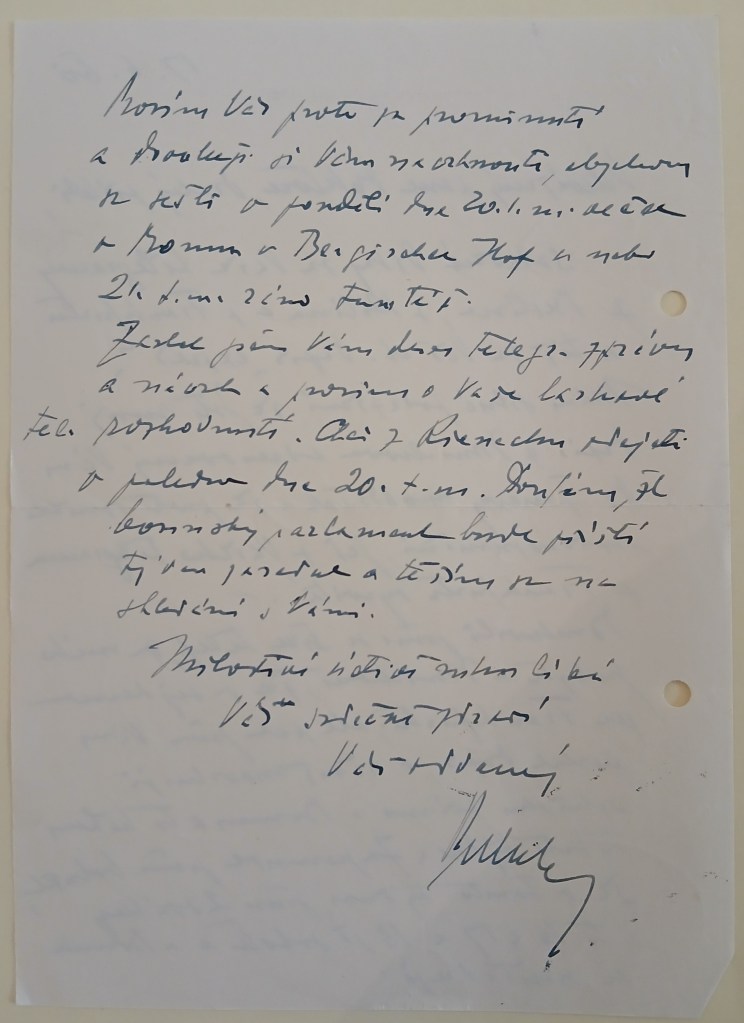

17.6.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

srdečné díky za Vaše telegramy z Berlna, z Kolína a z Frankfurtu a též za Váš ctěný dopis „expres“. Mám silné podezření, že jste můj dopis z Mnichova adresovaný Vám do Ženevy neobdržel a že zde vzniklo nedorozumění, jež z Vašeho telegramu z Frankfurtu vysvitá.

Domluvili jsme se sice telefonicky za mého pobytu v Mnichově, že se sejdeme ve Frankfurtu, ale pak jsem Vám poslal dopis, v němž navrhuji schůzku přímo v Bonnu, a to během tohoto týdne. Zapomněl jsem bohužel, že v tomto týdnu jsou 2 svátky, a to 16 a 17 a 18 je sobota a v Bonnu se neúřaduje.

Prosím Vás proto za prominutí a dovoluji si Vám navrhnouti, abychom se sešli v pondělí dne 20. t.m. večer v Bonnu v Bergischer Hof a nebo 21. t.m. ráno tamtéž.

Zaslal jsem Vám dnes telegr. zprávu a návrh a prosím o Vaše laskavé tel. rozhodnutí. Chci z Rienecku odjeti v poledne dne 20. t.m. Doufám, že bonnský parlament bude příští týden zasedat a těším se na shledání s Vámi.

Milostivé uctivě ruku líbá

Vás srdečně zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

Heartfelt thanks for your telegrams from Berlin, Cologne and Frankfurt and also for your esteemed “express” letter. I strongly suspect that you did not receive my letter from Munich addressed to you in Geneva and that there was a misunderstanding here, which will become clear from your telegram from Frankfurt.

We agreed by telephone during my stay in Munich that we would meet in Frankfurt, but then I sent you a letter in which I propose a meeting directly in Bonn, during this week. Unfortunately, I forgot that there are 2 holidays this week, namely the 16th and 17th and the 18th are Saturdays and there are no offices in Bonn.

Therefore, I beg your pardon and allow me to suggest that we meet on Monday, the 20th, in the evening in Bonn at the Bergischer Hof or on the 21st, in the morning there.

I sent you a telegram today. report and proposal and I ask for your kind decision. I want to leave Rieneck at noon on the 20th. I hope that the Bonn parliament will be in session next week and I look forward to seeing you.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

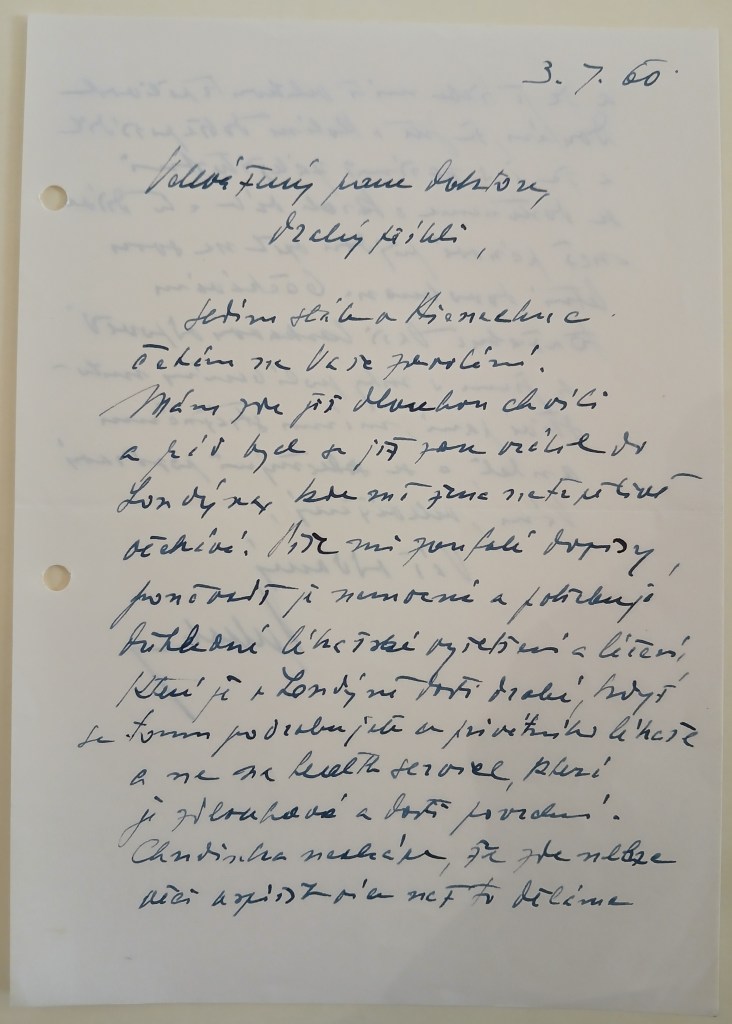

3.7.60 (Rieneck)

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

sedím stále v Rienecku a čekám na Vaše zavolání. Mám zde již dlouhou chvíli a rád bych se již zas vrátil do Londýna, kde mě žena netrpělivě očekává. Píše mi zoufalé dopisy, poněvadž je nemocná a potřebuje důkladné lékařské vyšetření a léčení, které je v Londýně dosti drahé, když se tomu podrobujete u privátního lékaře a ne na health service, které je zdlouhavé a dosti povrchní. Chudinka nechápe, že zde nelze věci uspíšit více než to děláme a že je třeba míti velikou trpělivost. Doufám, že jste v Kolíně dobře pořídil a že i s našimi záležitostmi se dostaneme o krok dále a to dříve než pánové půjdou opět na svou dovolenou. Očekávám toužebně Vaši laskavou odpověď a jsem s ruky políbením milostivé paní, mému strážnému anděli, a se srdečnými pozdravy Vám, velevážený,

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I am still sitting in Rieneck and waiting for your call. I have been here for a long time and I would like to return to London, where my wife is impatiently waiting for me. She writes me desperate letters because she is ill and needs a thorough medical examination and treatment, which is quite expensive in London if you undergo it with a private doctor and not with the health service, which is lengthy and rather superficial. My poor wife does not understand that things cannot be rushed here any more than we do and that great patience is needed. I hope that you have made good arrangements in Cologne and that we will also get a step further with our affairs before the gentlemen go on their vacation again. I eagerly await your kind answer, kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand, my guardian angel,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

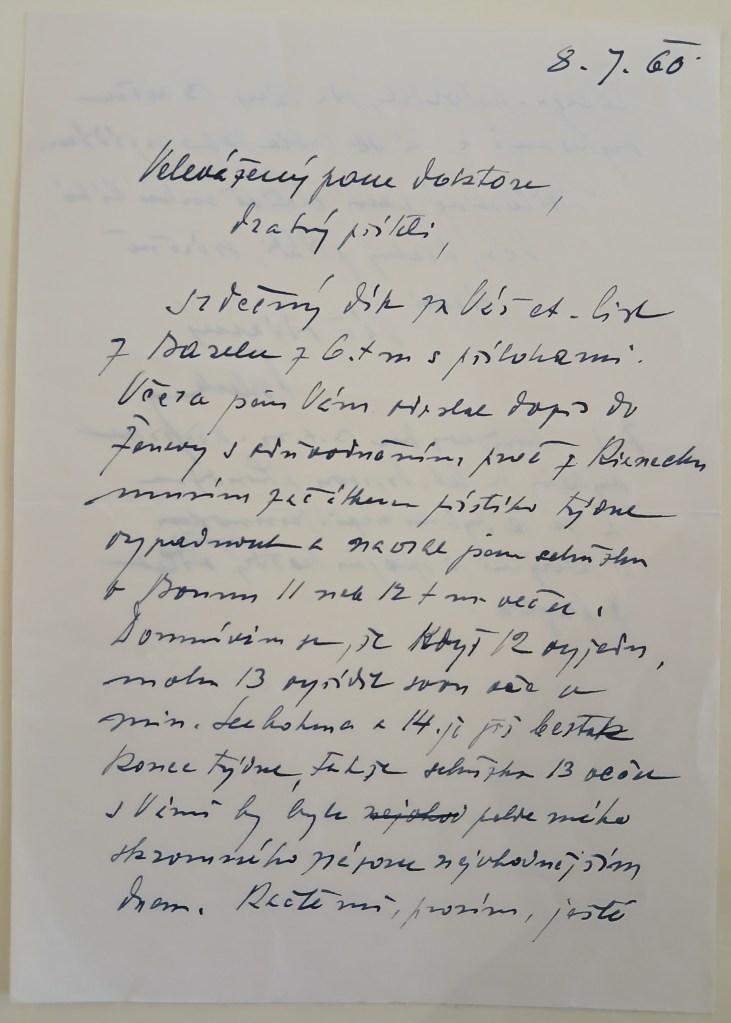

8.7.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

srdečný dík za Váš ctěný list z Baselu z 6. t.m. s přílohami. Včera jsem Vám odeslal dopis do Ženevy s odůvodněním, proč z Rienecku musím začátkem příštího týdne vypadnout (?) a navrhl jsem schůzku v Bonnu 11 nebo 12 t.m. večer. Domnívám se, že když 12 vyjedu, mohu 13 vyřídit svou věc u min. Seebohma a 14 je již beztak konec týdne, takže schůzka 13 večer s Vámi by byla podle mého skromného názoru nejvhodnějším dnem. Račte mi, prosím, ještě telegr. potvrdit, zda Vám 13 večer vyhovuje a já se podle toho zařídím. Milostivé paní uctivě ruku líbá,

Vás, drahý příteli, srdečně zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

heartfelt thanks for your esteemed letter from Basel of the 6th with attachments. Yesterday I sent you a letter to Geneva with the justification why I have to leave Rieneck at the beginning of next week (?) and I proposed a meeting in Bonn on the 11th or 12th in the evening. I believe that if I leave on the 12th, I can take care of my business with Minister Seebohm on the 13th and the 14th is already the end of the week anyway, so a meeting with you on the 13th evening would be, in my humble opinion, the most suitable day. Please confirm by telegram whether the 13th evening suits you and I will make arrangements accordingly.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

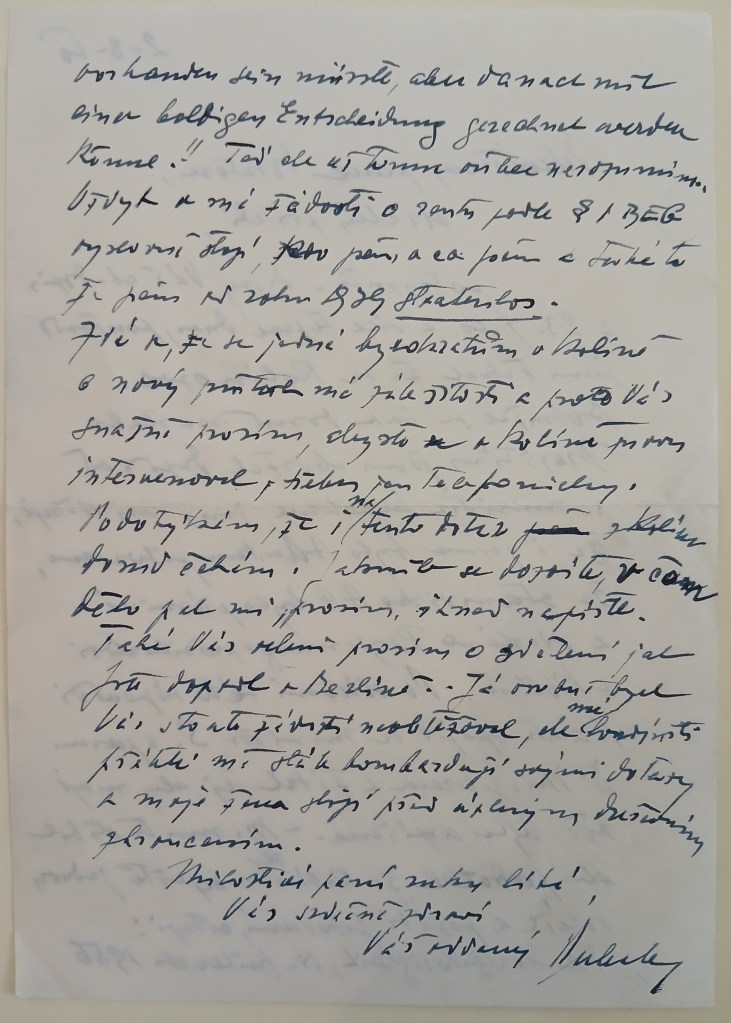

2.8.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

potvrzuji s díky Váš ctěný dopis z 23.7.60 a sice teprve dnes, poněvadž jsem čekal, že se Kolín ozve. Bohužel se tak dosud nestalo. Mezitím jsem obdržel dopis od p. ministra Seebohma, jenž mi sděluje, že i jemu bylo A Amtem potvrzeno, že stanovisko AA bylo příznivé a odesláno Regierungspräsidentovi v Kolíně. Po obdržení této odpovědi A-amt spojil se ministr S. S panem Dr. Mirgelerem a žádal jej, aby moje věc byla uspíšena. M. mu to slíbil, ale podotkl, že Kolín se mne ještě jednou dotáže a požádá potvrzení, cituji: „der Staatenhorigkeit, die früher als 1956 vorhanden sein müsste, aber danach mit einer boldigen Entscheidung gerechnet werden könne“. Teď ale už tomu vůbec nerozumím. Vždyť v mé žádosti o rentu podle § 1 BEG výslovně stojí, kdo jsem a co jsem a také to že jsem od roku 1939 staatenlos.

Zlé je, že se jedná byrokratům v Kolíně o nový (???) mé záležitosti a proto Vás snažně prosím, abyste v Kolíně znovu intervenoval, třeba jen telefonicky. Podotýkám, že i na tento dotaz z Kolína dosud čekám. Jakmile se dozvíte, v čem dělo?, pak mi, prosím, ihned napište. Také Vás velmi prosím o sdělení, jak jste dopadl v Berlíně. Já osobně bych Vás s touto žádostí neobtěžoval, ale mí londýnští přátelé mě stále bombardují svými dotazy a moje žena stojí před úplným duševním zhroucením.

Milostivé paní ruku líbá, Vás srdečně zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I confirm with thanks your esteemed letter of 23.7.60, replying today, because I was expecting Cologne to respond. Unfortunately, this has not happened yet. In the meantime, I have received a letter from Mr. Minister Seebohm, who informs me that he too was confirmed by the A-Amt that the AA’s opinion was favorable and sent to the Regierungspräsident in Cologne. After receiving this reply from the A-Amt, Minister S. contacted Dr. Mirgeler and asked him to expedite my case. M. promised him this, but pointed out that Cologne would ask me again and ask for confirmation, I quote: “der Staatenhorigkeit, die früher als 1956 vorhanden sein müsste, aber danach mit einer boldigen Entscheidung gerechnet werden könne”. But now I don’t understand it at all. After all, my application for a pension according to § 1 BEG explicitly states who I am and what I am and also that I have been stateless since 1939.

The bad thing is that this is a new (???) of my affairs for the bureaucrats in Cologne and therefore I strongly ask you to intervene again in Cologne, even if only by phone. I would like to point out that I am still waiting for this inquiry from Cologne. As soon as you find out what happened, please write to me immediately. I also ask you to tell me how you ended up in Berlin. I personally would not bother you with this request, but my London friends are constantly bombarding me with their questions and my wife is on the verge of a complete mental breakdown.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

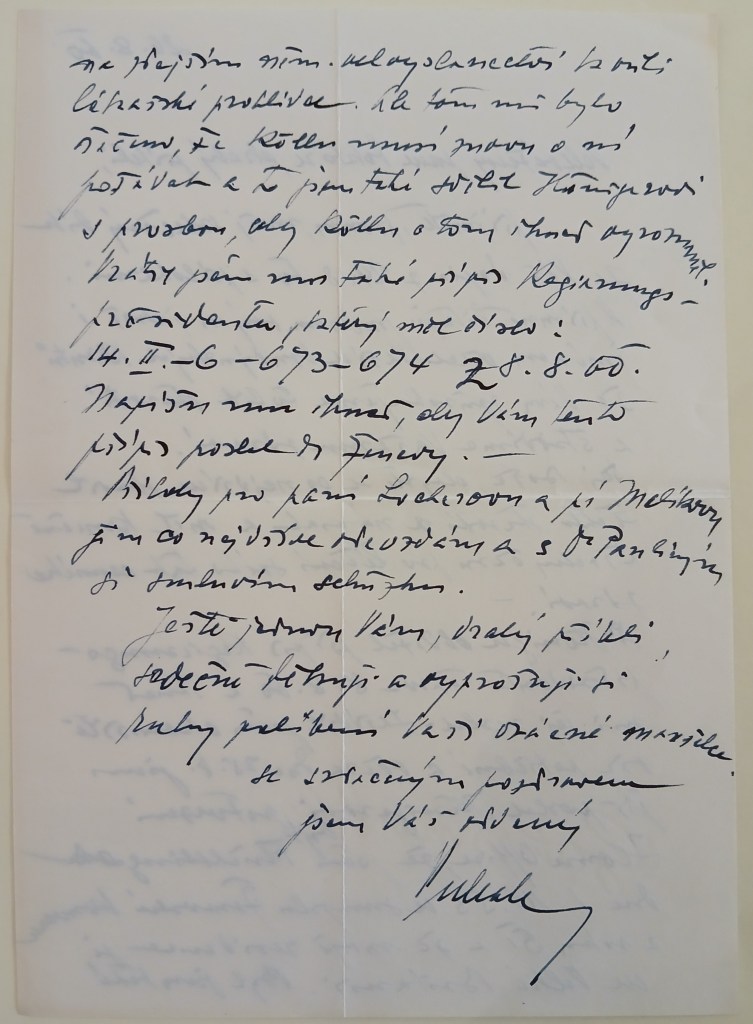

26.8.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

přijměte, prosím, můj srdečný dík za Váš dopis z 24.8.60 s přílohami. Upřímně lituji jménem svým jakož i jménem všech Vašich londýnských klientů, že Vám způsobujeme tolik starostí a škodíme Vašemu zdraví.

Dej Bože, abyste se co nejdříve zbavil těchto starostí o návrat a měl konečně trochu času pro léčení svého tak cenného zdraví.

Dr.Höniger obdržel přípis Regierungspräsidenta teprve 8.8.60 a ihned mi jej zaslal. Zařídil jsem okamžitě vše potřebné a včera dne 25.8. jsem již poslal Hönigerovi potvrzení Home Office, že jsem byl Flüchtling (ode) dne 1.10.53 ve smyslu Ženevské konvence z roku 51 a že moje residence je ve Velké Británii. Byl jsem také na zdejším německém velvyslanectví kvůli lékařské prohlídce. Ale tam mi bylo řečeno, že Köln musí znovu o ní požádat a to jsem také sdělil Hönigerovi s prosbou, aby Köln o tom ihned vyrozuměl. Vrátil jsem mu také přípis Regierungspräsidenta, který měl číslo: 14.II.-6-673-674 28.8.60. Napíšu mu ihned, aby Vám tento přípis poslal do Ženevy.

Přílohy pro paní Locherovou a paní Malíkovou jim co nejdříve odevzdám a s Dr. Paulínym si smluvím schůzku.

Ještě jednou Vám, drahý příteli, srdečně děkuji a vyprošuji si ruky políbení Vaší vzácné manželce.

Se srdečným pozdavem

jsem Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend

please accept my heartfelt thanks for your letter of 24.8.60 with the enclosures. I sincerely regret, on my own behalf and on behalf of all your London clients, that we are causing you so much trouble and harming your health.

May God grant that you may be rid of these worries about returning as soon as possible and finally have some time to treat your precious health.

Dr. Höniger received the Regierungspräsident’s letter only on 8.8.60 and sent it to me immediately. I immediately arranged everything necessary and yesterday, 25.8. I already sent Höniger a confirmation from the Home Office that I was a Flüchtling (from) on 1.10.53 within the meaning of the Geneva Convention of 51 and that my residence is in Great Britain. I also went to the German embassy here for a medical examination. But I was told there that Cologne had to apply for it again and I also told Höniger about this, asking that Cologne understand this immediately. I also returned to him the letter from the Regierungspräsident, which had the number: 14.II.-6-673-674 28.8.60. I will write to him immediately to send this letter to you in Geneva.

I will hand over the enclosures for Mrs. Locherová and Mrs. Malíková to them as soon as possible and I will arrange a meeting with Dr. Paulíny.

Once again, my dear friend, I thank you heartily and with a hand kiss to your honorable wife

Yours faithfully

Prchala

16.9.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

mám za to, že jste již opět v Ženevě a doufám, že Vás svým dopisem neobtěžuji. Doufám také, že jste si po tak namáhavé práci alespoň trochu odpočinul a že zdravotně se cítíte nyní lépe.

O obsahu Vašeho telegramu a dopisu nás již podrobně informoval přítel Dr. A a nezbývá než Vás obdivovat a Vám za Vaši obětavou práci mnohokráte děkovat. Zdá se, že to teď již dlouho trvat nebude a že vbrzku dojednáte věci definitivně.

Mě osobně velmi znepokojuje mlčení Kolína. Nedostal jsem dosud ani „Erklärung“, který jsem měl podepsat, ani povolání k lékařské prohlídce. Höniger sice slíbil, že po své dovolené, která končila 6.9., zajede do Kolína a o mé věci osobně pohovoří s Reg. Presidentem, ale dosud jsem bez zprávy jak z Kolína tak od Hönigera. A proto Vás prosím, abyste Vy se na to ještě jednou podíval, a to proto, poněvad6 Vám věří a vím, že bez Vaší intervence se nic nevyřídí.

Milostivé paní uctivě ruku líbám, Vás, drahý příteli, srdečně zdravím

a jsem Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I believe you are back in Geneva and I hope I am not bothering you with my letter. I also hope that you have at least rested a little after such strenuous work and that you are now feeling better in health.

We have already been informed in detail about the content of your telegram and letter by our friend Dr. A and there is nothing left but to admire you and thank you many times for your dedicated work. It seems that it will not be long now and that you will soon arrange things definitively.

I am personally very concerned about the silence of Cologne. I have not yet received either the “Erklalung” that I was supposed to sign or the summons for a medical examination. Honiger promised that after his vacation, which ended on September 6, he would go to Cologne and personally discuss my case with the Prime Minister, but I have still not heard from either Cologne or Honiger. And that’s why I’m asking you to take another look at it, because I trust you and I know that nothing will be resolved without your intervention.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

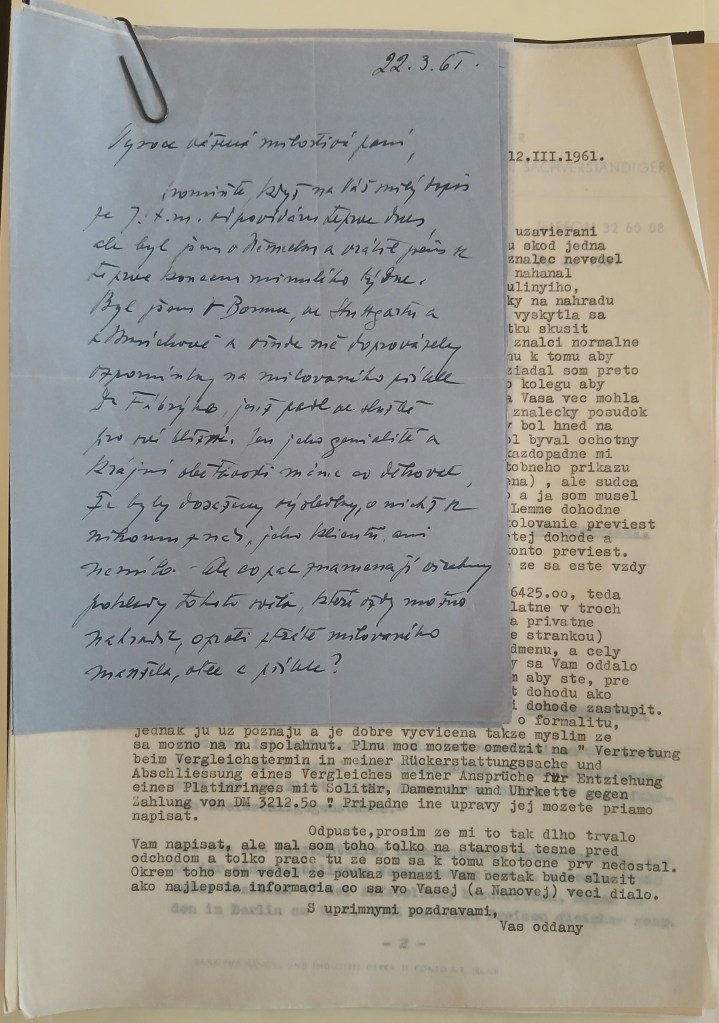

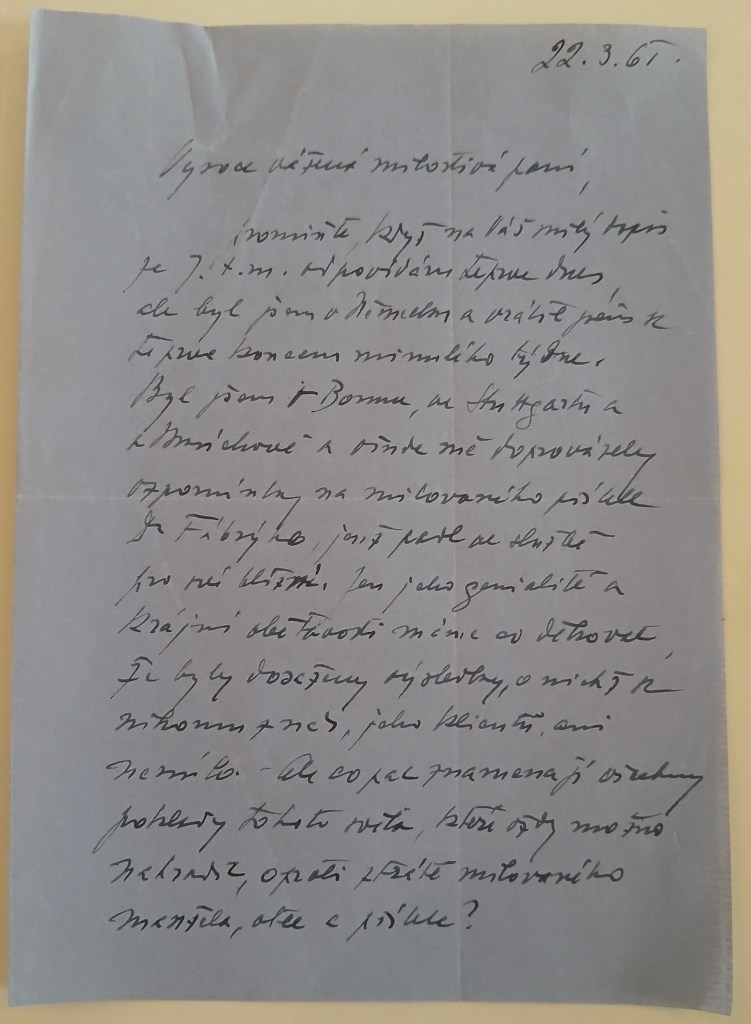

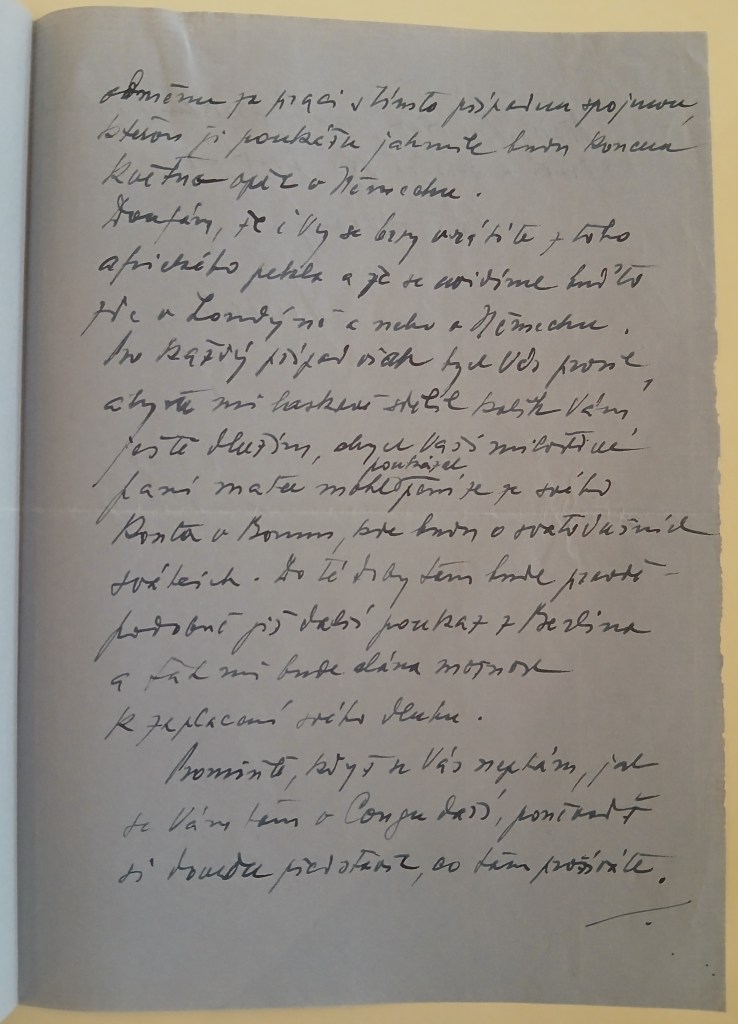

22.3.61

Vysoce vážená milostivá paní,

promiňte, když na Váš milý dopis ze 7. t.m. odpovídám teprve dnes, ale byl jsem v Německu a vrátil jsem se teprve koncem minulého týdne. Byl jsem v Bonnu, ve Stuttgartu a Mnichově a všude mě doprovázely vzpomínky na milovaného přítele Dr. Fábryho, jenž padl ve službě pro své blízké. Jen jeho genialitě a krajní obětavosti máme co děkovat, že byly dosažena výsledky, o nichž se nikomu z nás, jeho klientů, ani nesnilo. Ale co pak znamenají všechny poklady tohoto světa, které vždy možno nahradit, oproti ztrátě milovaného manžela, otce a přítele?

Stále ještě se nemohu smířit s jeho odchodem a mrzí mne, že jsem mu nemohl osobně poděkovat za jeho vzácnoua opravdu přátelskou službu, kterou prokázal mi a mé rodině.

V sobotu dne 20. t.m. obdržel jsem dopis od pana Dr. Vladimíra z Conga. Upřímně ho lituji a doufám, že se vrátí zdráv a co nejdříve z tohoto afrického pekla. Potvrzuje mi to, co mi před týdnem vyřídila telefonicky Vaše milostivá slečna dcera a paní Tágová, od níž jsem dostal dopis po svém příjezdu z Německa. Doufám, že koncem května budu opět v Bonnu a pak si dovolím zaslat Vám, milostivá, zbytek svého dluhu z druhé částky náhrady, která, jak předpokládám, bude do té doby už určitě v mé bance v Bonnu.

V červnu pak chci opět na léčení do Bad Kissingen. Žena tam chce také, ale teprve v srpnu, poněvadž někdo z nás zde musí zůstat. Takový je předpisCzech Trust Fundu, v jehož domě chceme bydlet i nadále. Do Ženevy se podívám až budu míti britský pas, což bude někdy na podzim.

Srdečně Vás, milostivá paní, oba zdravíme, já uctivě ruku líbám a jsem

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Madam,

I apologize for only replying to your kind letter of the 7th, but I was in Germany and only returned at the end of last week. I was in Bonn, Stuttgart and Munich and everywhere I was accompanied by memories of my beloved friend Dr. Fábry, who fell in the service of his loved ones. It is only to his genius and extreme dedication that we have something to thank for that results were achieved that none of us, his clients, could even dream of. But what are all the treasures of this world, which can always be replaced, compared to the loss of a beloved husband, father and friend?

I still cannot come to terms with his passing and I regret that I was not able to thank him personally for his precious and truly friendly service that he rendered to me and my family.

On Saturday, the 20th, I received a letter from Dr. Vladimír from Congo. I sincerely feel sorry for him and hope that he will return safely and as soon as possible from this African hell. I am confirmed by what your gracious daughter and Mrs. Tágová told me by telephone a week ago, from whom I received a letter after my arrival from Germany. I hope that I will be in Bonn again at the end of May and then I will take the liberty of sending you, my lady, the rest of my debt from the second amount of compensation, which, as I assume, will certainly be in my bank in Bonn by then.

In June I want to go to Bad Kissingen again for treatment. My wife also wants to go there, but not until August, because one of us has to stay here. This is the regulation of the Czech Trust Fund, in whose house we want to continue living. I will travel to Geneva when I have a British passport, which will be sometime in the autumn.

We both warmly greet you, dear Madam, I respectfully kiss your hand and I am

Yours faithfully

Prchala

From Gen. Lev Prchala to Vladimir Fabry, 22 March 1961:

22.3.61

Dear Doctor,

Thank you very much for your esteemed letter of 12.3.61, which I received only on the 20th of this month, just after sending my letter to Mrs. Tagova. She sent me the letter on 7.3.61, while I was in Germany, and asked me only for a short statement that I agreed with the expert’s estimate of 6,425DM. I sent this to her immediately after my return, i.e. on the 20th of this month, with my notarized signature. She did not ask for a power of attorney from me, because she hopes that it will be possible to do without a “Vergleich”. I also promised her a special reward for the work connected with this case, which I will pay her as soon as I am back in Germany at the end of May.

I hope that you will also return soon from this African hell and that we will see each other either here in London or in Germany. Just in case, I would ask you to kindly tell me how much I still owe you, so that I can transfer the money to your gracious mother from my account in Bonn, where I will be during the Whitsun holidays. By then, another order from Berlin will probably be there and I will be given the opportunity to pay my debt.

Excuse me if I do not ask you how you are doing in Congo, because I can imagine what you are going through there.

I wish you much success and good health and send you my warmest regards

Yours faithfully

Prchala

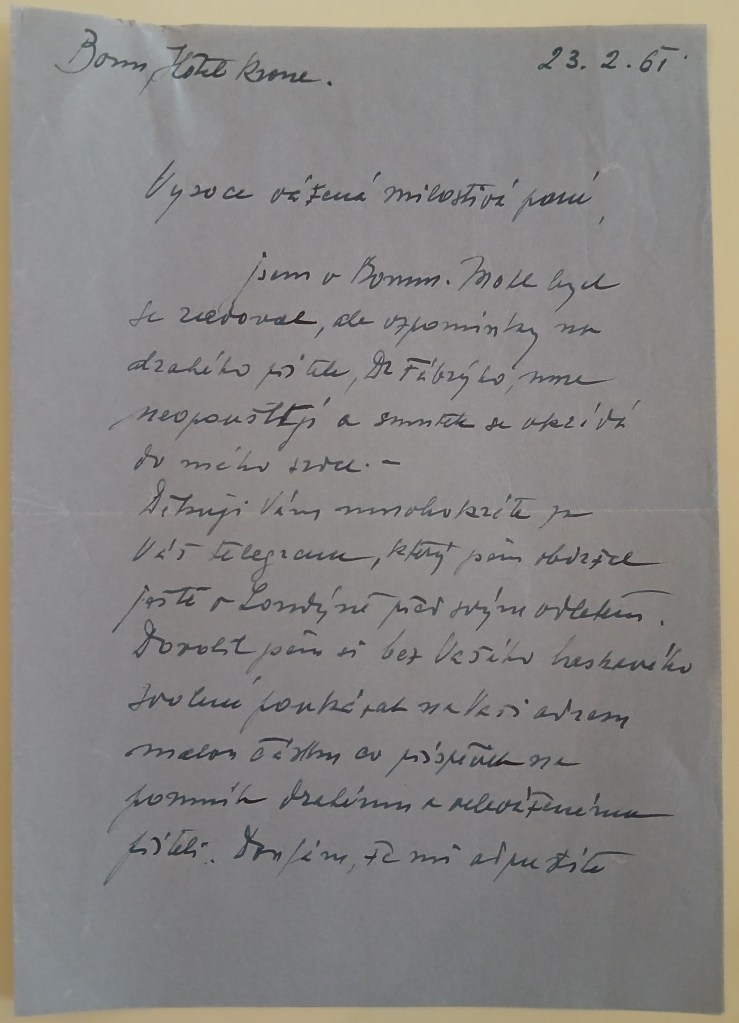

From Prchala to Madam Olga Fabry-Palka, 23 February 1961:

Bonn, Hotel Krone. 23.2.61

Dear Madam,

I am in Bonn. I could be happy, but the memories of my dear friend, Dr. Fabry, do not leave me and sadness returns to my heart.

Thank you very much for your telegram, which I received in London before my departure. Without your kind permission, I took the liberty of sending to your address a small sum as a contribution to the monument to a dear and esteemed friend. I hope you will forgive me and with a hand kiss I am

Yours faithfully

Prchala