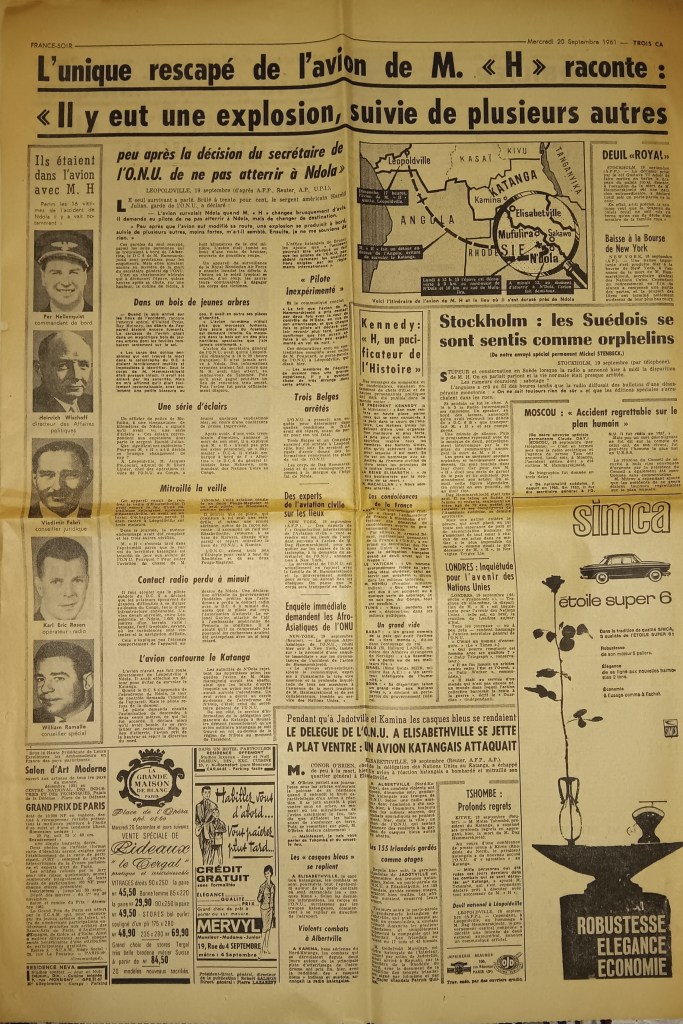

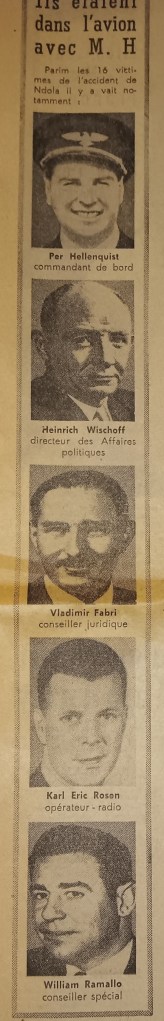

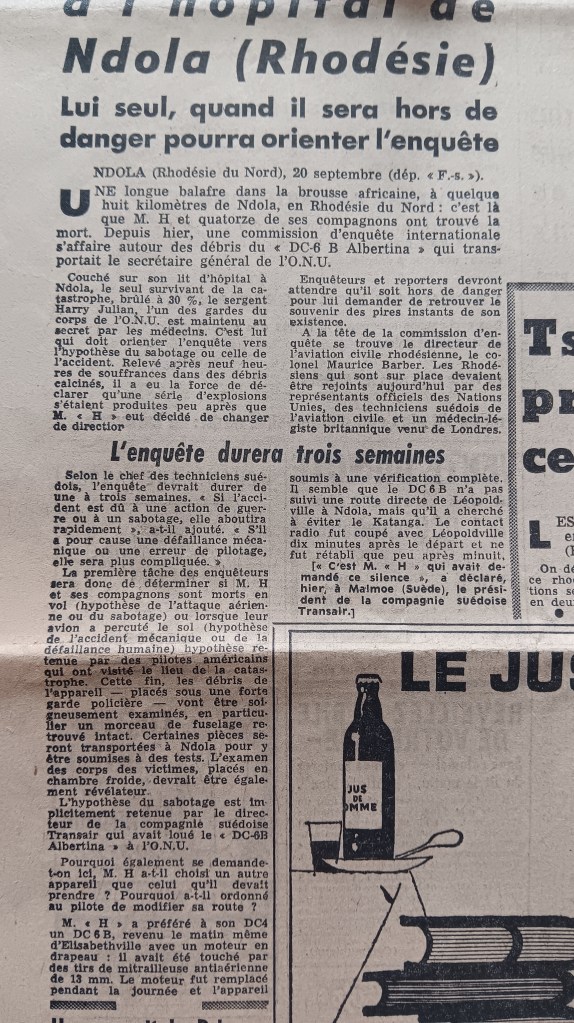

With gratitude to Susan Williams for her most recent essay, published in The Yale Review, “Revisiting Dag Hammarskjold’s Mysterious Death”, here is a larger selection of international papers from my archive, 19-27 September 1961. Harold Julien was the only survivor of the Albertina crash, and for too long his testimony has been undervalued and deliberately suppressed, it is time to take his evidence seriously.

From her essay: “In 2019, new information emerged relating to Julien’s stay in the Ndola hospital, provided by the government of Zimbabwe to the current U.N. inquiry. This fresh information reveals that Rhodesian authorities actively sought to prevent Julien’s statements from being made public. A senior Rhodesian intelligence official instructed Julien’s medical superintendent that “no one of his hospital staff must talk about this,” in relation to Julien’s statements that he had seen sparks in the sky. The superintendent and another doctor were warned about “the security angle” and asked “to make sure that none of their staff talked.

“Justice Othman views this new evidence as significant. In his view, “a general undervaluing of the evidence of Harold Julien…may have affected the exhaustiveness of the earlier inquiries’ consideration of the possible hypotheses.”

From Williams’ essay: “[…]the 1961-62 official inquiries concluded that the first sighting of the crash site was at 3:10 p.m. on September 18 by a RRAF pilot flying overhead; at around the same time, there was a report of a sighting by the two aforementioned charcoal burners. Following these reports, police vehicles and ambulances were immediately sent to the site.

“But a mass of evidence has emerged that shows that many people knew that the plane had crashed – and where – long before it was officially located. Indeed, the crash site was reported to the Northern Rhodesian authorities between 9:00 and 9:30 a.m. by Timothy Kankasa. Some charcoal burners had come across the burning plane in the morning and, in great concern, rushed to tell him. The men reported the crash to him, rather than to the police, because they mistrusted and feared the white authorities.”

From Williams’ essay: “[…] Colonel Don G. Gaylor […] was sent to Ndola on September 15 by the Pentagon.[…] Gaylor was one of three U.S. air attaches who are known to have flown to Ndola airport during the period of September 15-18. […] According to a letter Gaylor wrote to an official Swedish investigator in 1994 (a letter I was recently sent by Hans Kristian Simensen, a Norwegian researcher who, like me, is assisting Justice Othman on a voluntary basis), Gaylor was in the control tower at Ndola airport on the night of September 17-18, waiting for Hammarskjold’s aircraft. The letter states that after the plane failed to arrive, he and his crew prepared for takeoff at first light to look for a crash site. Gaylor wrote that he spotted the wreckage shortly after dawn and immediately contacted the “Ndola rescue frequency and gave them the map coordinates of the site.” His letter adds: “Then I circled the site for a considerable period to give the ground party a point of reference.” This account is consistent with Gaylor’s memoir.”

“It should be noted that there is a discrepancy between this claim by Gaylor and a report by Matlick to the U.S. Secretary of State on September 22, which states that Gaylor had wanted to search in the morning but was not allowed to do so by the Rhodesian civil authorities. Matlick adds that Gaylor flew the second aircraft to spot the crash site in the afternoon, following a sighting by a RRAF aircraft; this was echoed by Squadron Leader John Mussell in his testimony to the Rhodesian Board of Investigation.

“Without further documentary evidence, we cannot resolve these conflicting pieces of evidence, or verify Gaylor’s claim that he found the crash site shortly after dawn. This makes it all the more important to obtain and study the report that Gaylor said he sent to the Pentagon: “My report to my superiors in the Pentagon was acknowledged with some accolades.”

From Williams’ essay: “On Tuesday, September 19, the day after Julien had been taken to the hospital, he was “slightly better.” Though “still dangerously ill,” he was expected to survive. A day later, he was reported as “holding his own.”

From Susan Williams’ book “Who Killed Hammarskjold?”, pages 186 and 187:

“[Bo] Virving stated that there were five [De Havilland] Doves in service of the Katangese air force in September 1961 at Kolwezi and Jadotville airports. They could stay airborne for three or four hours and their speed could match that of Hammarskjold’s DC6 in level flight; and in a dive from above they could increase their speed. It would be possible for the crew of the Dove to drop a small explosive device on to an aircraft below, then pull out of the dive. Virving had developed this theory about a Dove because on the day that Hammarskjold’s body was flown out to Sweden, he had seen a Dove at Ndola airport and discovered that it had a hole in its floor, which was apparently used for aerial photography. A man could lie there, he realized, telling the pilot ‘right, left, up, down’ and at a given moment let fall a small projectile.

“The theory that a Dove could be used in this way was later confirmed by Mercenary Commander, the memoir of the mercenary Jerry Puren[…]

“The Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry Report acknowledged that a Dove with bombing capacity was found in September 1961 at Ndola–but after the crash. ‘One De Havilland Dove belonging to the Katanga Government,’ it stated, ‘was after the 18th September armed by removing a door and placing a machine gun on the floor to fire through the opening.’ The Dove had not, it stated, been at Ndola on the day of the crash, but elsewhere: ‘On 17th September this and possibly another were in the hands of the United Nations at Elisabethville. Three Doves were then in the Republic of South Africa undergoing examination.’

“A Dove plane at Ndola also caused consternation at the British Embassy in Leopoldville in the week after the crash of the Albertina. Ambassador Riches sent a telegram to the Foreign Office on 24 September 1961, reporting that, according to Matlick, the U.S. Air Attache in Leopoldville who had just returned from Ndola, a Dove aircraft with Katangan air force markings had taken off from Ndola for Kolwezi the day before, carrying mercenaries. He had given this information to the UN, who had passed it on to Riches. ‘Report could do us serious damage here,’ warned Riches to London.

“Virving’s suspicions about the use of a Dove against the Albertina were heightened when he went to Elisabethville in 1962 and found that the Katangese Doves had disappeared during the August 1961 UN action to expel mercenaries. Significantly, their logbooks had been left behind. Then Virving found the Pretoria workshop where the Doves would normally have been serviced and sought information ‘for historical purposes’; but after two years’ wait he was told that no information could be given.”

From Williams’ essay: “Maria Julien arrived in Ndola on Thursday, September 22, and was with Harry on the final day and night of his life. He was sedated and did not speak much. But she knew he was fully in his senses, because he asked about a chain that he had sent to her to be repaired — a chain to a medallion of St. Christopher, the patron saint of travelers. They were both devout Catholics, and Maria had called a priest to her husband’s bedside.

“But on the morning of the next day, her husband died — despite the expectation that he would survive. This was five days after the crash. The coroner’s summary report listed the cause as “Renal failure due to extensive burns following aircraft accident.”

[…]

“As Sgt. Julien was the only person left to describe what has happened on the flight, his recollections should have been crucial to the investigations of the Rhodesian Commission. But the commission discounted Julien’s statements to the nurses, writing: “No attention need be paid to remarks, later in the week, about sparks in the sky. They either relate to the fire after the crash, or a symptom of his then condition.” Even Julien’s comment about the plane having blown up, made to police inspector Allen, was not given serious attention.

“The senior medical staff at the hospital dismissed Julien’s recollections of the crash as the ramblings of a sick man; his reference to “sparks in the sky” was attributed to uraemia. But Dr. Lowenthal took a different view. He stated that Julien’s recollections were spoken during a plasma transfusion and before an injection of pethidine, which means that Julien had not been sedated at the time. Lowenthal felt so strongly about the need to establish this truth that he participated in the Rhodesian hearings as a volunteer witness; he insisted that when Julien spoke about the crash, he was “lucid and coherent.”

In honor of Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday today, here is some encouragement from him: “I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant.”