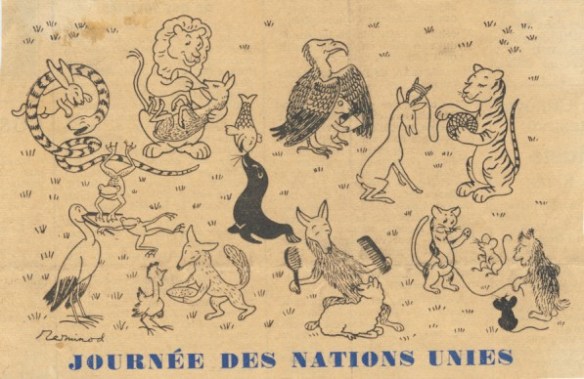

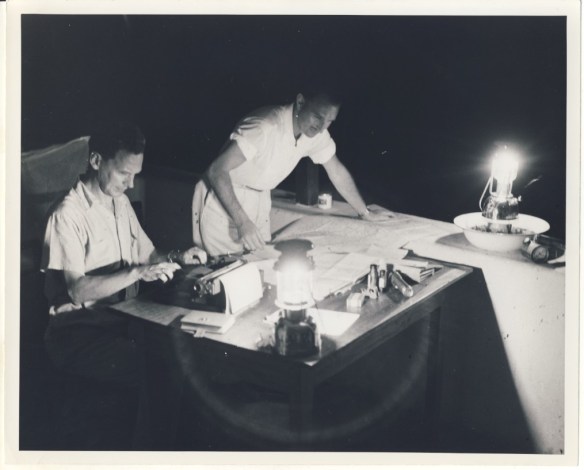

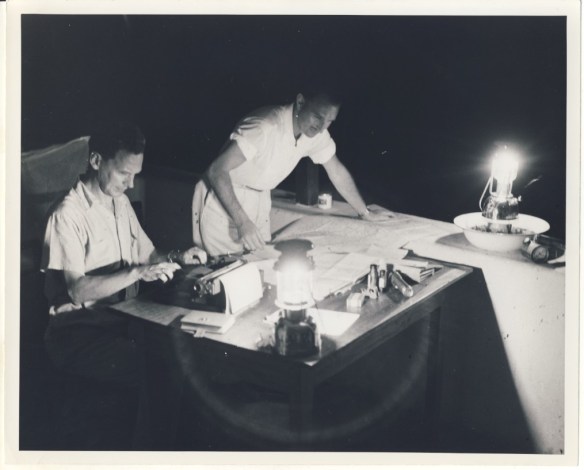

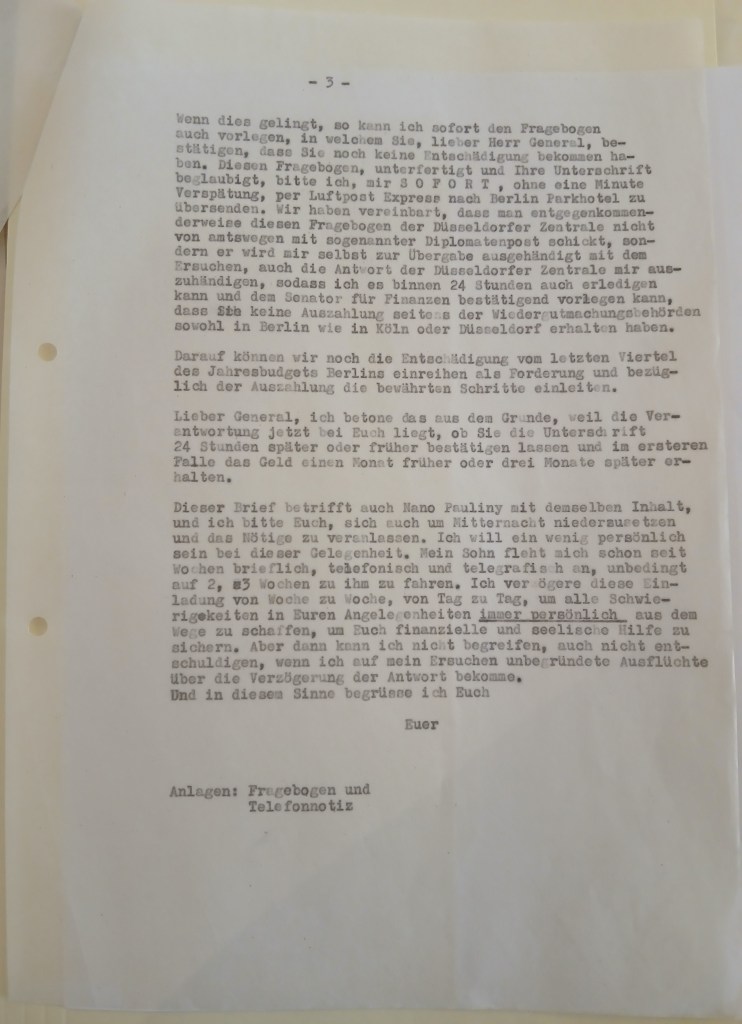

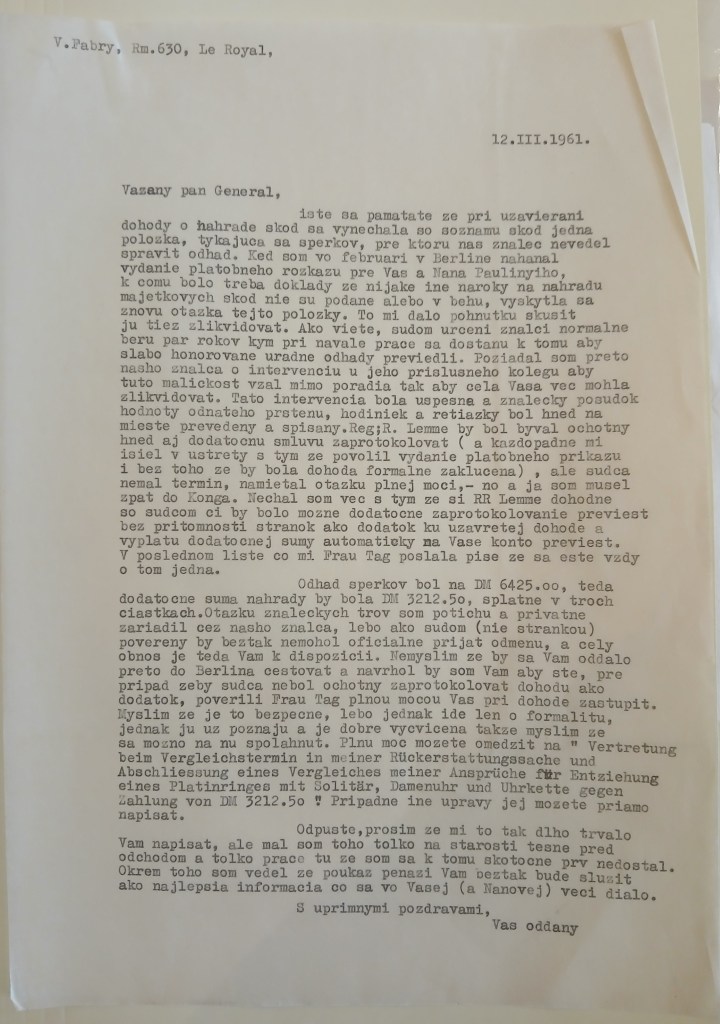

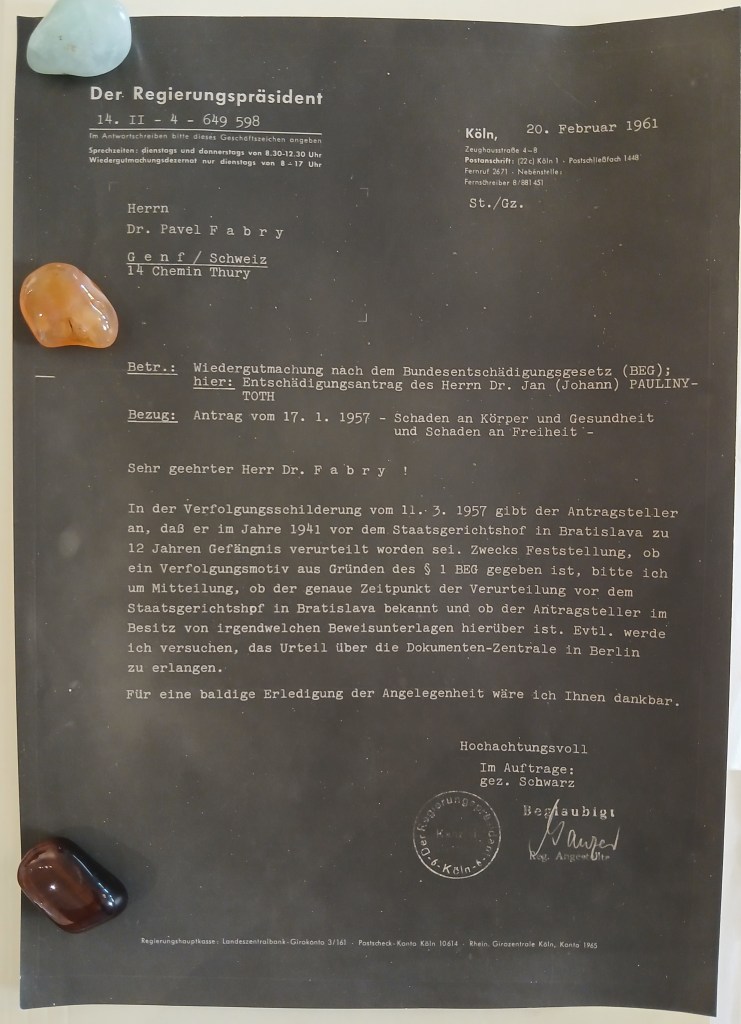

With great respect to Army General Lev Prchala and to our grandfather Dr. Pavel Fabry – Czechoslovakian heroes, defenders of democratic freedom, symbols of resistance against nazis and fascists! These are the last letters between them, from 1960, with related documents included. Translations will be added later. Pavel died of a heart attack in Berlin on 19 December 1960, he was 69. Vlado took over the remaining legal work from his father, somehow finding time for it while also working for the UN in the Congo. Vlado’s letter to the General is sent from Hotel Le Royal, Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), 12 March 1961. It brings tears to my eyes how much love they had for their friends, the personal sacrifices they were willing to make for each other – my cup runs over in their memory.

Thanks to Miroslav Kamenik for transcribing and translating all the handwritten letters here!

17.5.60

Vážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

byl bych Vám nesmírně vděčen, kdybyste mi alespoň několika slovy naznačil jak stojí záležitosti Vašich Londýnských klientů, resp. klientek, které mě svými dotazy stále bombardují.Také bych rád věděl, zda máte v úmyslu se se mnou v Německu viděti, poněvadž čas utíká a můj odlet do Mnichova se blíží. Počítám, že přiletím pravděpodobně 2 nebo 3 června a že se v Mnichově zdržím až týden. Pak bych Vám byl k dispozici a vše závisí z Vašich plánů, kdy a kde byste mě potřeboval.

Těším se na Vaši laskavou odpověď a jsem s ruky políbením milostivé paní a se srdečnými pozdravy

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I would be extremely grateful if you could give me at least a few words about the state of cases of your London clients, who are constantly bombarding me with their inquiries. I would also like to know whether you intend to see me in Germany, as time is running out and my departure for Munich is approaching. I expect to arrive probably on the 2nd or 3rd of June and to stay in Munich for up to a week. Then I would be at your disposal, and it all depends on your plans, when and where you would need me.

I look forward to your kind reply and I am with a kiss on the hand of your wife and with warm regards

Faithfully your

Prchala

20.5.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

dnes jsem obdržel letecký lístek London – Mnichov – London od Česko – Sud. Něm federálního výboru pro let dne 2. června 1960.

Poletím tedy ve čtvrtek dne 2. června do Mnichova a zdržím se tam asi týden. Zároveň jsem byl uvědoměn, že čestné pozvánky budou rozposlány v příštích dnech. Doufám, že pozvánku pro sebe a Vaši milostivou obdržíte co nejdříve.

A nyní mám k Vám, vzázcný příteli, jednu velikou prosbu. Abych zde měl pevný důkaz pro nutnost své jízdy do Německa, zašlete mně, prosím, telegram, v němž mě vyzýváte k schůzce v Německu. Dejž Bůh, aby taková schůzka se stala doopravdy možnou.

S ruky políbením velevážené milostivé paní a se srdečnými pozdravy jsem Váš oddaný,

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

today I received a London – Munich – London ticket from the Czech – SudetenGerman Federal Committee for the flight on June 2, 1960.

I will fly to Munich on Thursday, June 2, and will stay there for about a week. At the same time, I was informed that the honorary invitations will be sent out in the coming days. I hope that you will receive the invitation for yourself and your ladyship as soon as possible.

And now I have one great request for you, dear friend. So that I may have solid proof of the necessity of my journey to Germany, please send me a telegram in which you invite me to a meeting in Germany. God grant that such a meeting may actually become possible.

I am with a kiss on the hand of your wife and with warm regards

Faithfully your

Prchala

28.5.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

dovolte, abych Vám srdečně poděkoval za telegram, který jsem právě obdržel. Telegrafoval jsem ihned do Mnichova, aby Vám zaslali čestnou pozvánku, o kterou jsem žádal již před několika týdny. Vysvětluji si tuto chybu jedině tím, že Ing. Simon je zavalen prací a pevně doufám, že tento faux pas okamžitě napraví.

Těším se velice na setkání s Vámi a Vaší milostivou paní, které uctivě líbám ruku.

Srdečně Vás zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

P.S. Tatsachenbericht jsem odevzdal pí. S a pí. M. V Mnichově bydlím v hotelu „Esplanade“ naproti hl. nádraží.

Dear Doctor, my friend,

let me to thank you most cordially for the telegram I have just received. I immediately telegraphed to Munich to have the honorary invitation sent to you, which I had requested several weeks ago. I can only explain this mistake by saying that Ing. Simon is overwhelmed with work and I firmly hope that he will rectify this faux pas immediately.

I am very much looking forward to meeting you and your honorable wife, whose hand I respectfully kiss.

Yours sincerely

Prchala

P.S. I handed over the Tatsachenbericht to Mrs. S and Mrs. M. In Munich I live in the hotel “Esplanade” opposite the main station.

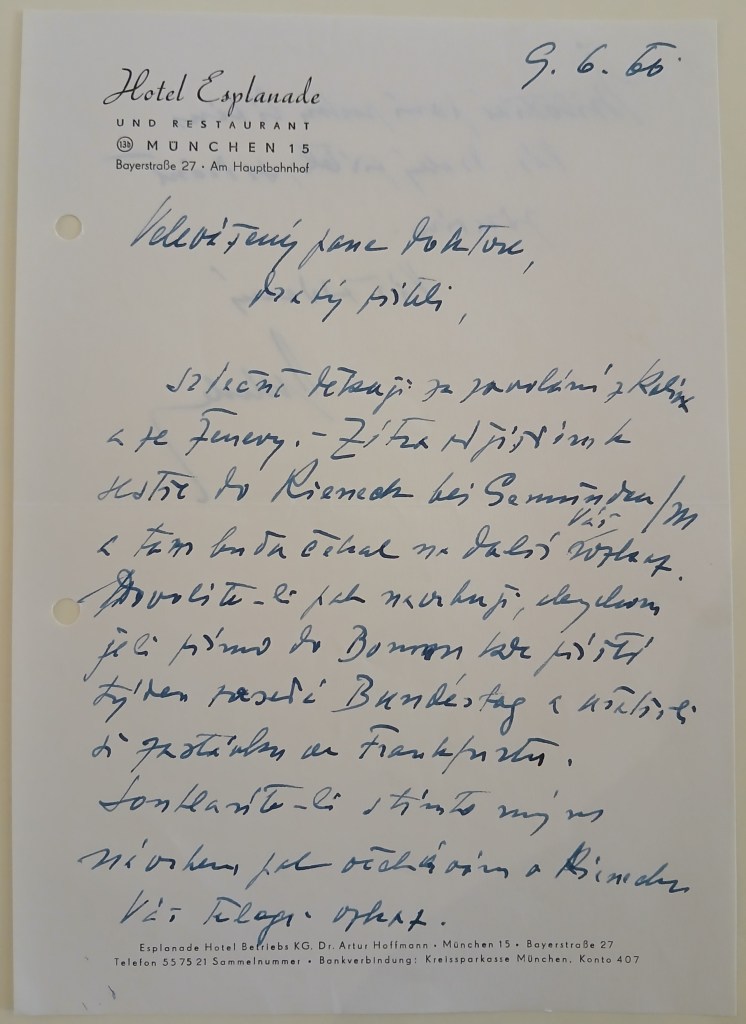

9.6.60, München, Hotel Esplanade

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

srdečně děkuji za zavolání z Kolína a ze Ženevy. Zítra odjíždím k sestře do Rieneck bei Gemünden / M a tam budu čekat na další Váš rozkaz. Dovolíte-li, pak navrhuji, abychom jeli přímo do Bonnu kde příští týden zasedá Bundestag a ušetřili si zastávku ve Frankfurtu. Souhlasíte-li s tímto mým návrhem, pak očekávám v Rienecku Váš telegr. vzkaz.

Milostivé paní ruku líbám,

Vás, drahý příteli, srdečně zdravím.

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

thank you very much for your call from Cologne and Geneva. Tomorrow I am leaving for my sister in Rieneck bei Gemünden / M and there I will await your further orders. If you allow me, I suggest that we go directly to Bonn where the Bundestag is in session next week and save ourselves a stopover in Frankfurt. If you agree with this proposal of mine, I am expecting your telegram in Rieneck.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

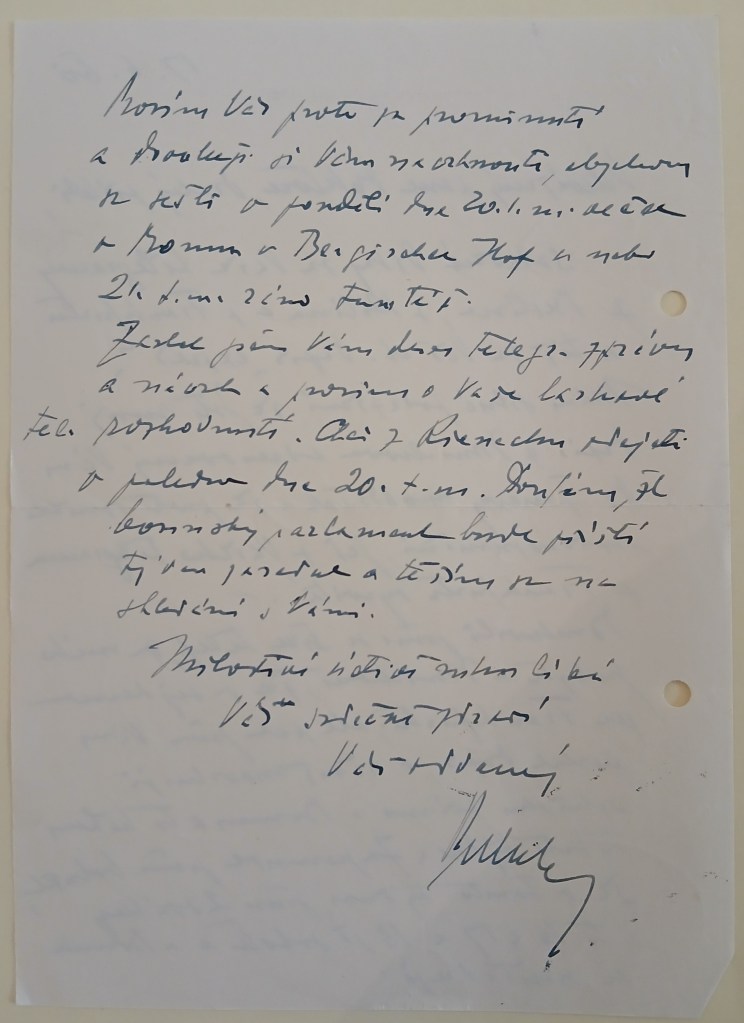

17.6.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

srdečné díky za Vaše telegramy z Berlna, z Kolína a z Frankfurtu a též za Váš ctěný dopis „expres“. Mám silné podezření, že jste můj dopis z Mnichova adresovaný Vám do Ženevy neobdržel a že zde vzniklo nedorozumění, jež z Vašeho telegramu z Frankfurtu vysvitá.

Domluvili jsme se sice telefonicky za mého pobytu v Mnichově, že se sejdeme ve Frankfurtu, ale pak jsem Vám poslal dopis, v němž navrhuji schůzku přímo v Bonnu, a to během tohoto týdne. Zapomněl jsem bohužel, že v tomto týdnu jsou 2 svátky, a to 16 a 17 a 18 je sobota a v Bonnu se neúřaduje.

Prosím Vás proto za prominutí a dovoluji si Vám navrhnouti, abychom se sešli v pondělí dne 20. t.m. večer v Bonnu v Bergischer Hof a nebo 21. t.m. ráno tamtéž.

Zaslal jsem Vám dnes telegr. zprávu a návrh a prosím o Vaše laskavé tel. rozhodnutí. Chci z Rienecku odjeti v poledne dne 20. t.m. Doufám, že bonnský parlament bude příští týden zasedat a těším se na shledání s Vámi.

Milostivé uctivě ruku líbá

Vás srdečně zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

Heartfelt thanks for your telegrams from Berlin, Cologne and Frankfurt and also for your esteemed “express” letter. I strongly suspect that you did not receive my letter from Munich addressed to you in Geneva and that there was a misunderstanding here, which will become clear from your telegram from Frankfurt.

We agreed by telephone during my stay in Munich that we would meet in Frankfurt, but then I sent you a letter in which I propose a meeting directly in Bonn, during this week. Unfortunately, I forgot that there are 2 holidays this week, namely the 16th and 17th and the 18th are Saturdays and there are no offices in Bonn.

Therefore, I beg your pardon and allow me to suggest that we meet on Monday, the 20th, in the evening in Bonn at the Bergischer Hof or on the 21st, in the morning there.

I sent you a telegram today. report and proposal and I ask for your kind decision. I want to leave Rieneck at noon on the 20th. I hope that the Bonn parliament will be in session next week and I look forward to seeing you.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

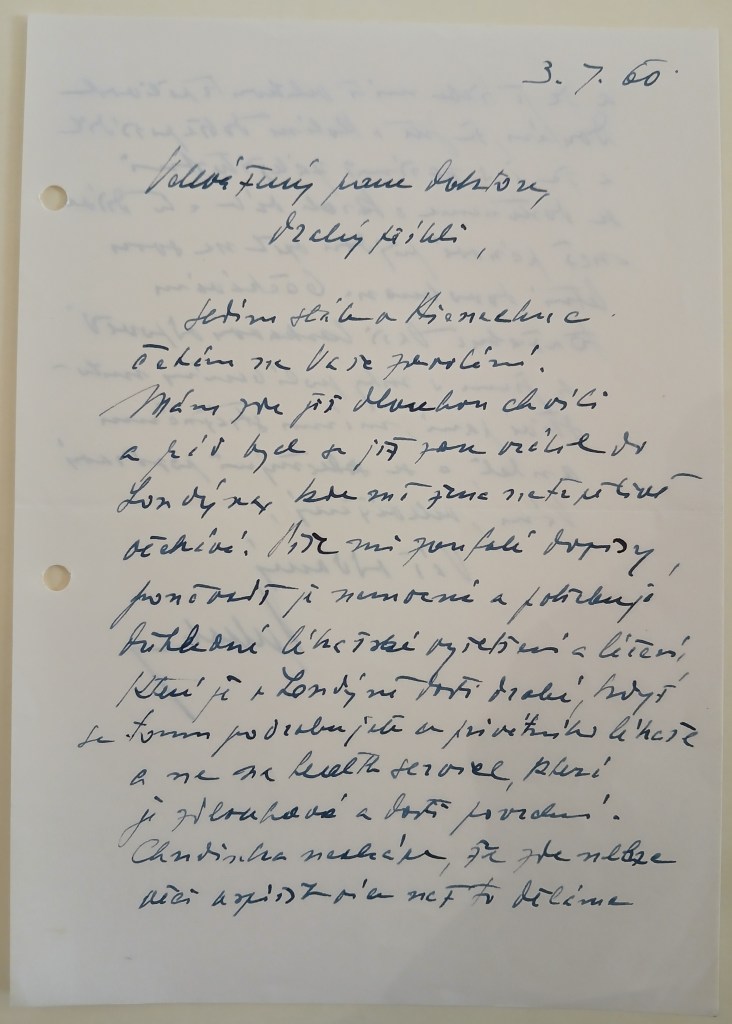

3.7.60 (Rieneck)

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

sedím stále v Rienecku a čekám na Vaše zavolání. Mám zde již dlouhou chvíli a rád bych se již zas vrátil do Londýna, kde mě žena netrpělivě očekává. Píše mi zoufalé dopisy, poněvadž je nemocná a potřebuje důkladné lékařské vyšetření a léčení, které je v Londýně dosti drahé, když se tomu podrobujete u privátního lékaře a ne na health service, které je zdlouhavé a dosti povrchní. Chudinka nechápe, že zde nelze věci uspíšit více než to děláme a že je třeba míti velikou trpělivost. Doufám, že jste v Kolíně dobře pořídil a že i s našimi záležitostmi se dostaneme o krok dále a to dříve než pánové půjdou opět na svou dovolenou. Očekávám toužebně Vaši laskavou odpověď a jsem s ruky políbením milostivé paní, mému strážnému anděli, a se srdečnými pozdravy Vám, velevážený,

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I am still sitting in Rieneck and waiting for your call. I have been here for a long time and I would like to return to London, where my wife is impatiently waiting for me. She writes me desperate letters because she is ill and needs a thorough medical examination and treatment, which is quite expensive in London if you undergo it with a private doctor and not with the health service, which is lengthy and rather superficial. My poor wife does not understand that things cannot be rushed here any more than we do and that great patience is needed. I hope that you have made good arrangements in Cologne and that we will also get a step further with our affairs before the gentlemen go on their vacation again. I eagerly await your kind answer, kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand, my guardian angel,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

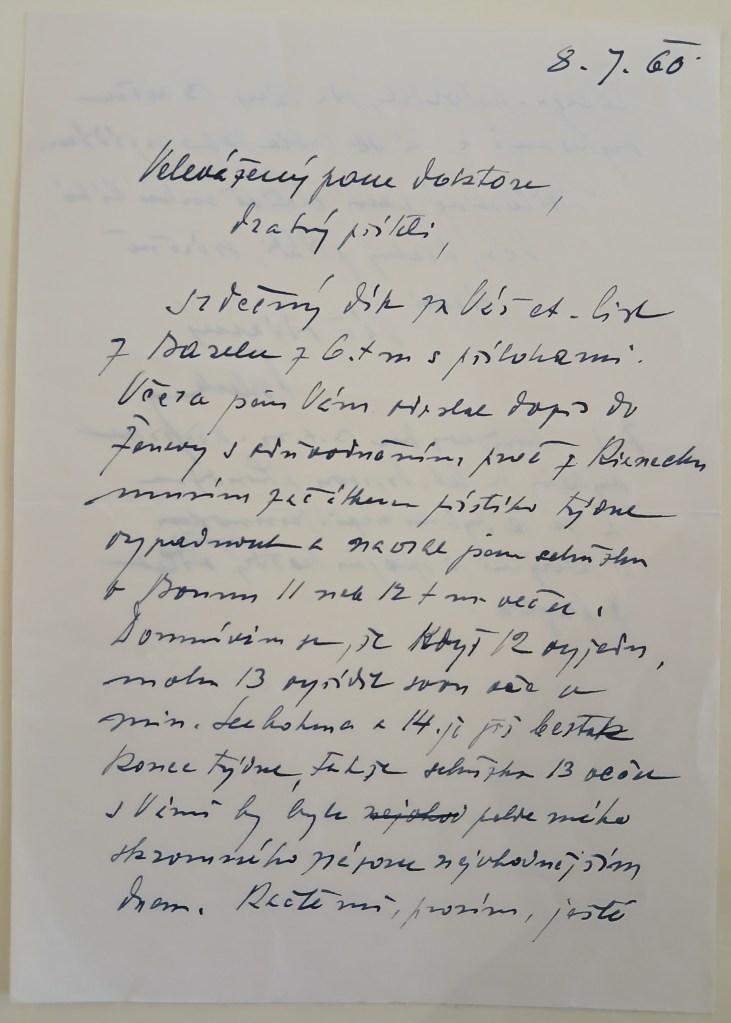

8.7.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

srdečný dík za Váš ctěný list z Baselu z 6. t.m. s přílohami. Včera jsem Vám odeslal dopis do Ženevy s odůvodněním, proč z Rienecku musím začátkem příštího týdne vypadnout (?) a navrhl jsem schůzku v Bonnu 11 nebo 12 t.m. večer. Domnívám se, že když 12 vyjedu, mohu 13 vyřídit svou věc u min. Seebohma a 14 je již beztak konec týdne, takže schůzka 13 večer s Vámi by byla podle mého skromného názoru nejvhodnějším dnem. Račte mi, prosím, ještě telegr. potvrdit, zda Vám 13 večer vyhovuje a já se podle toho zařídím. Milostivé paní uctivě ruku líbá,

Vás, drahý příteli, srdečně zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

heartfelt thanks for your esteemed letter from Basel of the 6th with attachments. Yesterday I sent you a letter to Geneva with the justification why I have to leave Rieneck at the beginning of next week (?) and I proposed a meeting in Bonn on the 11th or 12th in the evening. I believe that if I leave on the 12th, I can take care of my business with Minister Seebohm on the 13th and the 14th is already the end of the week anyway, so a meeting with you on the 13th evening would be, in my humble opinion, the most suitable day. Please confirm by telegram whether the 13th evening suits you and I will make arrangements accordingly.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

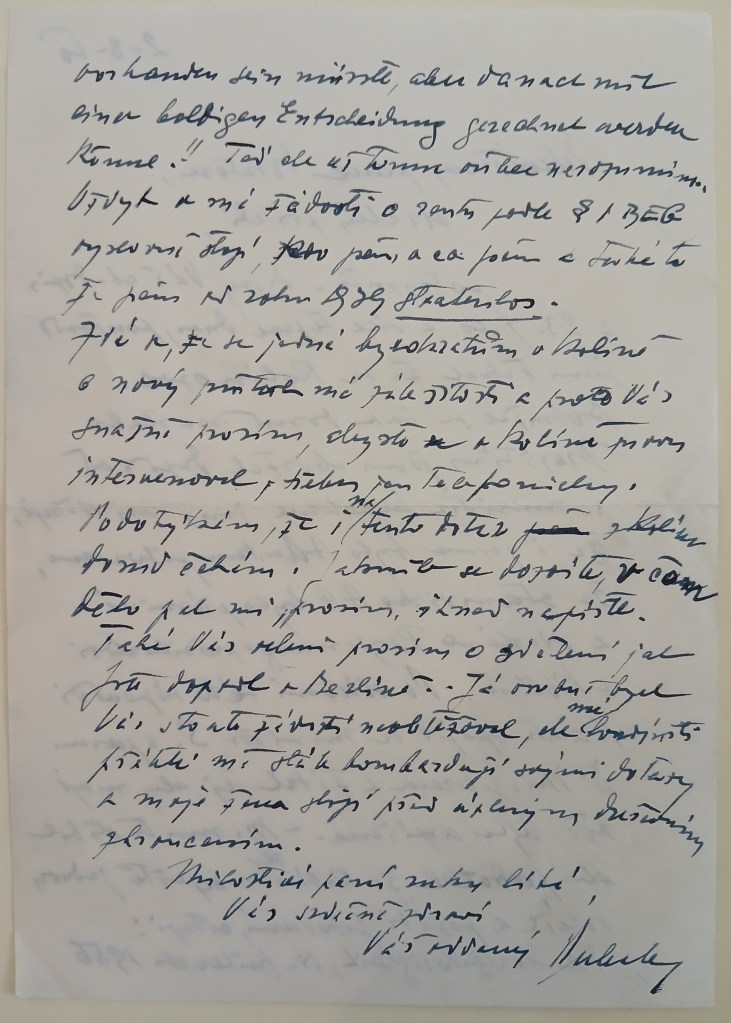

2.8.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

potvrzuji s díky Váš ctěný dopis z 23.7.60 a sice teprve dnes, poněvadž jsem čekal, že se Kolín ozve. Bohužel se tak dosud nestalo. Mezitím jsem obdržel dopis od p. ministra Seebohma, jenž mi sděluje, že i jemu bylo A Amtem potvrzeno, že stanovisko AA bylo příznivé a odesláno Regierungspräsidentovi v Kolíně. Po obdržení této odpovědi A-amt spojil se ministr S. S panem Dr. Mirgelerem a žádal jej, aby moje věc byla uspíšena. M. mu to slíbil, ale podotkl, že Kolín se mne ještě jednou dotáže a požádá potvrzení, cituji: „der Staatenhorigkeit, die früher als 1956 vorhanden sein müsste, aber danach mit einer boldigen Entscheidung gerechnet werden könne“. Teď ale už tomu vůbec nerozumím. Vždyť v mé žádosti o rentu podle § 1 BEG výslovně stojí, kdo jsem a co jsem a také to že jsem od roku 1939 staatenlos.

Zlé je, že se jedná byrokratům v Kolíně o nový (???) mé záležitosti a proto Vás snažně prosím, abyste v Kolíně znovu intervenoval, třeba jen telefonicky. Podotýkám, že i na tento dotaz z Kolína dosud čekám. Jakmile se dozvíte, v čem dělo?, pak mi, prosím, ihned napište. Také Vás velmi prosím o sdělení, jak jste dopadl v Berlíně. Já osobně bych Vás s touto žádostí neobtěžoval, ale mí londýnští přátelé mě stále bombardují svými dotazy a moje žena stojí před úplným duševním zhroucením.

Milostivé paní ruku líbá, Vás srdečně zdraví

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I confirm with thanks your esteemed letter of 23.7.60, replying today, because I was expecting Cologne to respond. Unfortunately, this has not happened yet. In the meantime, I have received a letter from Mr. Minister Seebohm, who informs me that he too was confirmed by the A-Amt that the AA’s opinion was favorable and sent to the Regierungspräsident in Cologne. After receiving this reply from the A-Amt, Minister S. contacted Dr. Mirgeler and asked him to expedite my case. M. promised him this, but pointed out that Cologne would ask me again and ask for confirmation, I quote: “der Staatenhorigkeit, die früher als 1956 vorhanden sein müsste, aber danach mit einer boldigen Entscheidung gerechnet werden könne”. But now I don’t understand it at all. After all, my application for a pension according to § 1 BEG explicitly states who I am and what I am and also that I have been stateless since 1939.

The bad thing is that this is a new (???) of my affairs for the bureaucrats in Cologne and therefore I strongly ask you to intervene again in Cologne, even if only by phone. I would like to point out that I am still waiting for this inquiry from Cologne. As soon as you find out what happened, please write to me immediately. I also ask you to tell me how you ended up in Berlin. I personally would not bother you with this request, but my London friends are constantly bombarding me with their questions and my wife is on the verge of a complete mental breakdown.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

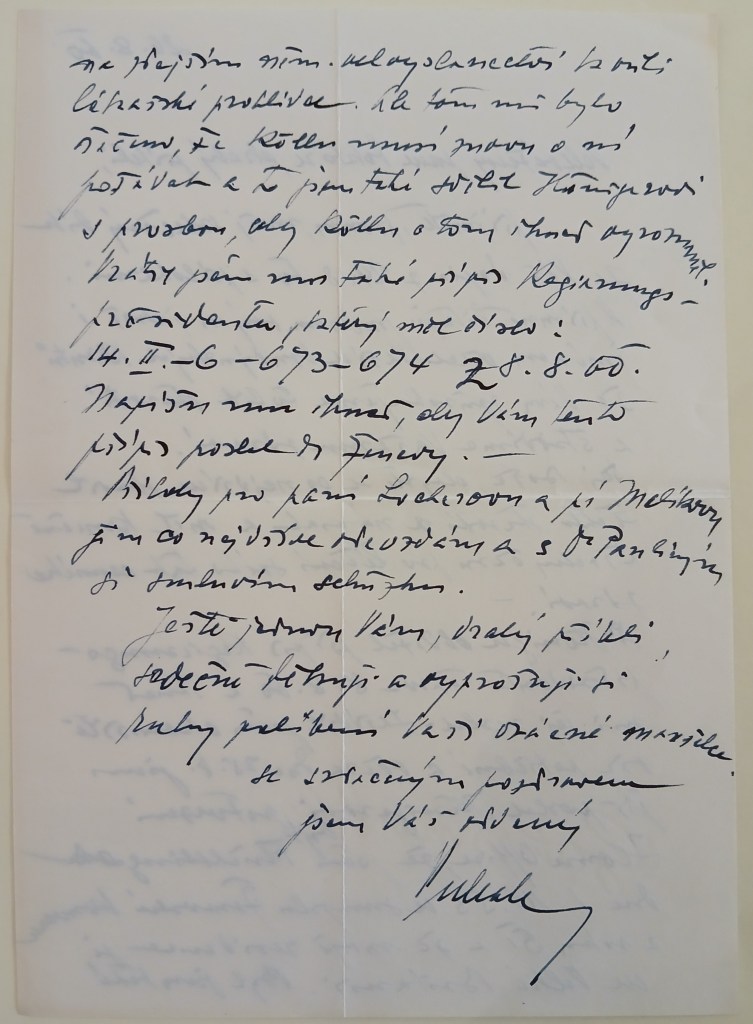

26.8.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

přijměte, prosím, můj srdečný dík za Váš dopis z 24.8.60 s přílohami. Upřímně lituji jménem svým jakož i jménem všech Vašich londýnských klientů, že Vám způsobujeme tolik starostí a škodíme Vašemu zdraví.

Dej Bože, abyste se co nejdříve zbavil těchto starostí o návrat a měl konečně trochu času pro léčení svého tak cenného zdraví.

Dr.Höniger obdržel přípis Regierungspräsidenta teprve 8.8.60 a ihned mi jej zaslal. Zařídil jsem okamžitě vše potřebné a včera dne 25.8. jsem již poslal Hönigerovi potvrzení Home Office, že jsem byl Flüchtling (ode) dne 1.10.53 ve smyslu Ženevské konvence z roku 51 a že moje residence je ve Velké Británii. Byl jsem také na zdejším německém velvyslanectví kvůli lékařské prohlídce. Ale tam mi bylo řečeno, že Köln musí znovu o ní požádat a to jsem také sdělil Hönigerovi s prosbou, aby Köln o tom ihned vyrozuměl. Vrátil jsem mu také přípis Regierungspräsidenta, který měl číslo: 14.II.-6-673-674 28.8.60. Napíšu mu ihned, aby Vám tento přípis poslal do Ženevy.

Přílohy pro paní Locherovou a paní Malíkovou jim co nejdříve odevzdám a s Dr. Paulínym si smluvím schůzku.

Ještě jednou Vám, drahý příteli, srdečně děkuji a vyprošuji si ruky políbení Vaší vzácné manželce.

Se srdečným pozdavem

jsem Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend

please accept my heartfelt thanks for your letter of 24.8.60 with the enclosures. I sincerely regret, on my own behalf and on behalf of all your London clients, that we are causing you so much trouble and harming your health.

May God grant that you may be rid of these worries about returning as soon as possible and finally have some time to treat your precious health.

Dr. Höniger received the Regierungspräsident’s letter only on 8.8.60 and sent it to me immediately. I immediately arranged everything necessary and yesterday, 25.8. I already sent Höniger a confirmation from the Home Office that I was a Flüchtling (from) on 1.10.53 within the meaning of the Geneva Convention of 51 and that my residence is in Great Britain. I also went to the German embassy here for a medical examination. But I was told there that Cologne had to apply for it again and I also told Höniger about this, asking that Cologne understand this immediately. I also returned to him the letter from the Regierungspräsident, which had the number: 14.II.-6-673-674 28.8.60. I will write to him immediately to send this letter to you in Geneva.

I will hand over the enclosures for Mrs. Locherová and Mrs. Malíková to them as soon as possible and I will arrange a meeting with Dr. Paulíny.

Once again, my dear friend, I thank you heartily and with a hand kiss to your honorable wife

Yours faithfully

Prchala

16.9.60

Velevážený pane doktore, drahý příteli,

mám za to, že jste již opět v Ženevě a doufám, že Vás svým dopisem neobtěžuji. Doufám také, že jste si po tak namáhavé práci alespoň trochu odpočinul a že zdravotně se cítíte nyní lépe.

O obsahu Vašeho telegramu a dopisu nás již podrobně informoval přítel Dr. A a nezbývá než Vás obdivovat a Vám za Vaši obětavou práci mnohokráte děkovat. Zdá se, že to teď již dlouho trvat nebude a že vbrzku dojednáte věci definitivně.

Mě osobně velmi znepokojuje mlčení Kolína. Nedostal jsem dosud ani „Erklärung“, který jsem měl podepsat, ani povolání k lékařské prohlídce. Höniger sice slíbil, že po své dovolené, která končila 6.9., zajede do Kolína a o mé věci osobně pohovoří s Reg. Presidentem, ale dosud jsem bez zprávy jak z Kolína tak od Hönigera. A proto Vás prosím, abyste Vy se na to ještě jednou podíval, a to proto, poněvad6 Vám věří a vím, že bez Vaší intervence se nic nevyřídí.

Milostivé paní uctivě ruku líbám, Vás, drahý příteli, srdečně zdravím

a jsem Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Doctor, my friend,

I believe you are back in Geneva and I hope I am not bothering you with my letter. I also hope that you have at least rested a little after such strenuous work and that you are now feeling better in health.

We have already been informed in detail about the content of your telegram and letter by our friend Dr. A and there is nothing left but to admire you and thank you many times for your dedicated work. It seems that it will not be long now and that you will soon arrange things definitively.

I am personally very concerned about the silence of Cologne. I have not yet received either the “Erklalung” that I was supposed to sign or the summons for a medical examination. Honiger promised that after his vacation, which ended on September 6, he would go to Cologne and personally discuss my case with the Prime Minister, but I have still not heard from either Cologne or Honiger. And that’s why I’m asking you to take another look at it, because I trust you and I know that nothing will be resolved without your intervention.

Kind kisses to your honorable wife’s hand,

I greet you warmly, my dear friend.

Yours faithfully

Prchala

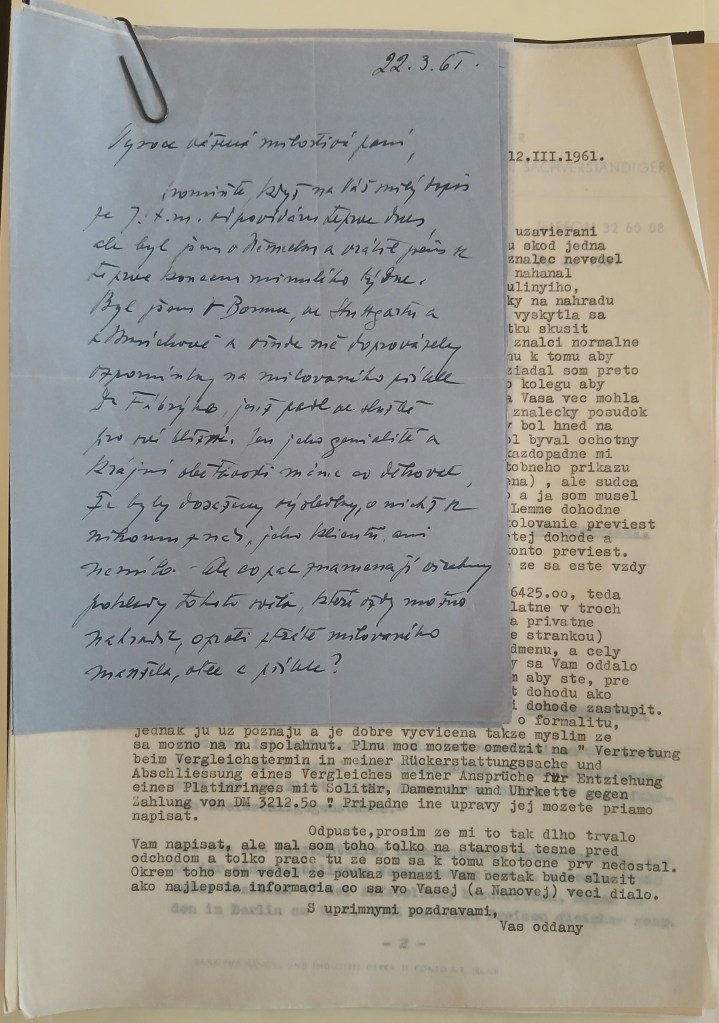

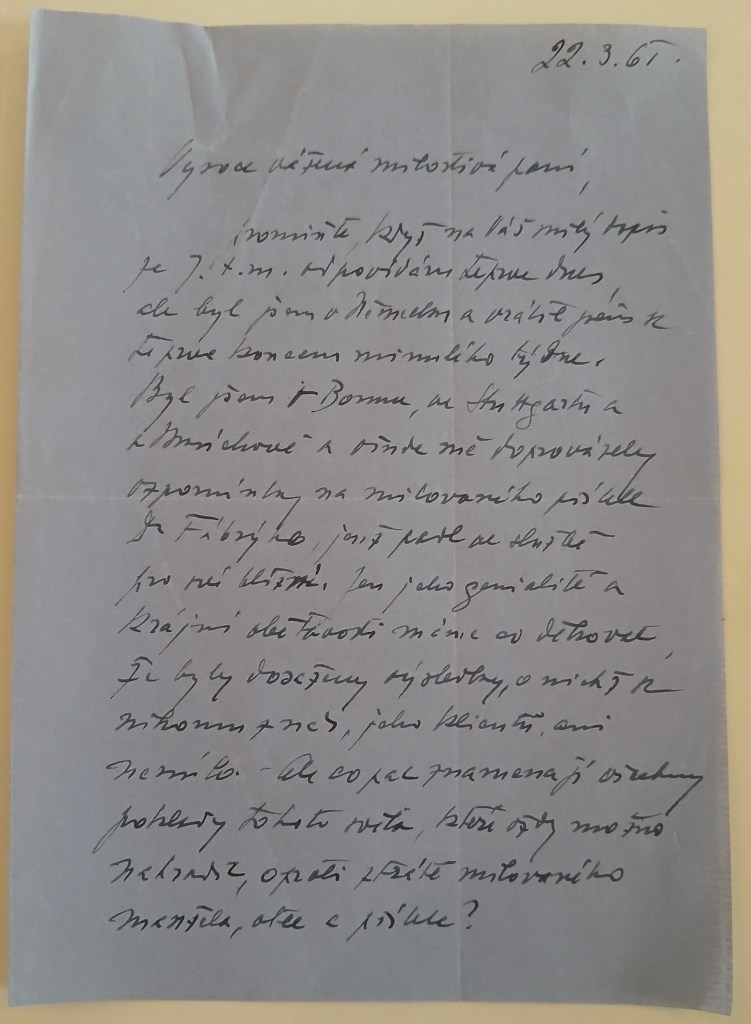

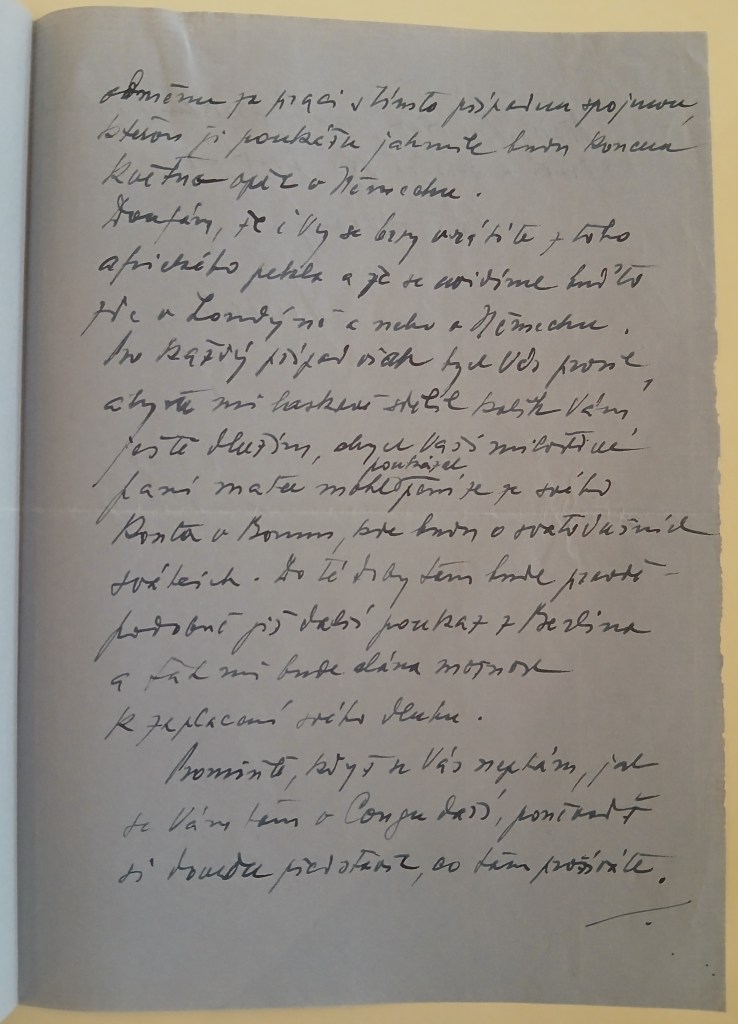

22.3.61

Vysoce vážená milostivá paní,

promiňte, když na Váš milý dopis ze 7. t.m. odpovídám teprve dnes, ale byl jsem v Německu a vrátil jsem se teprve koncem minulého týdne. Byl jsem v Bonnu, ve Stuttgartu a Mnichově a všude mě doprovázely vzpomínky na milovaného přítele Dr. Fábryho, jenž padl ve službě pro své blízké. Jen jeho genialitě a krajní obětavosti máme co děkovat, že byly dosažena výsledky, o nichž se nikomu z nás, jeho klientů, ani nesnilo. Ale co pak znamenají všechny poklady tohoto světa, které vždy možno nahradit, oproti ztrátě milovaného manžela, otce a přítele?

Stále ještě se nemohu smířit s jeho odchodem a mrzí mne, že jsem mu nemohl osobně poděkovat za jeho vzácnoua opravdu přátelskou službu, kterou prokázal mi a mé rodině.

V sobotu dne 20. t.m. obdržel jsem dopis od pana Dr. Vladimíra z Conga. Upřímně ho lituji a doufám, že se vrátí zdráv a co nejdříve z tohoto afrického pekla. Potvrzuje mi to, co mi před týdnem vyřídila telefonicky Vaše milostivá slečna dcera a paní Tágová, od níž jsem dostal dopis po svém příjezdu z Německa. Doufám, že koncem května budu opět v Bonnu a pak si dovolím zaslat Vám, milostivá, zbytek svého dluhu z druhé částky náhrady, která, jak předpokládám, bude do té doby už určitě v mé bance v Bonnu.

V červnu pak chci opět na léčení do Bad Kissingen. Žena tam chce také, ale teprve v srpnu, poněvadž někdo z nás zde musí zůstat. Takový je předpisCzech Trust Fundu, v jehož domě chceme bydlet i nadále. Do Ženevy se podívám až budu míti britský pas, což bude někdy na podzim.

Srdečně Vás, milostivá paní, oba zdravíme, já uctivě ruku líbám a jsem

Váš oddaný

Prchala

Dear Madam,

I apologize for only replying to your kind letter of the 7th, but I was in Germany and only returned at the end of last week. I was in Bonn, Stuttgart and Munich and everywhere I was accompanied by memories of my beloved friend Dr. Fábry, who fell in the service of his loved ones. It is only to his genius and extreme dedication that we have something to thank for that results were achieved that none of us, his clients, could even dream of. But what are all the treasures of this world, which can always be replaced, compared to the loss of a beloved husband, father and friend?

I still cannot come to terms with his passing and I regret that I was not able to thank him personally for his precious and truly friendly service that he rendered to me and my family.

On Saturday, the 20th, I received a letter from Dr. Vladimír from Congo. I sincerely feel sorry for him and hope that he will return safely and as soon as possible from this African hell. I am confirmed by what your gracious daughter and Mrs. Tágová told me by telephone a week ago, from whom I received a letter after my arrival from Germany. I hope that I will be in Bonn again at the end of May and then I will take the liberty of sending you, my lady, the rest of my debt from the second amount of compensation, which, as I assume, will certainly be in my bank in Bonn by then.

In June I want to go to Bad Kissingen again for treatment. My wife also wants to go there, but not until August, because one of us has to stay here. This is the regulation of the Czech Trust Fund, in whose house we want to continue living. I will travel to Geneva when I have a British passport, which will be sometime in the autumn.

We both warmly greet you, dear Madam, I respectfully kiss your hand and I am

Yours faithfully

Prchala

From Gen. Lev Prchala to Vladimir Fabry, 22 March 1961:

22.3.61

Dear Doctor,

Thank you very much for your esteemed letter of 12.3.61, which I received only on the 20th of this month, just after sending my letter to Mrs. Tagova. She sent me the letter on 7.3.61, while I was in Germany, and asked me only for a short statement that I agreed with the expert’s estimate of 6,425DM. I sent this to her immediately after my return, i.e. on the 20th of this month, with my notarized signature. She did not ask for a power of attorney from me, because she hopes that it will be possible to do without a “Vergleich”. I also promised her a special reward for the work connected with this case, which I will pay her as soon as I am back in Germany at the end of May.

I hope that you will also return soon from this African hell and that we will see each other either here in London or in Germany. Just in case, I would ask you to kindly tell me how much I still owe you, so that I can transfer the money to your gracious mother from my account in Bonn, where I will be during the Whitsun holidays. By then, another order from Berlin will probably be there and I will be given the opportunity to pay my debt.

Excuse me if I do not ask you how you are doing in Congo, because I can imagine what you are going through there.

I wish you much success and good health and send you my warmest regards

Yours faithfully

Prchala

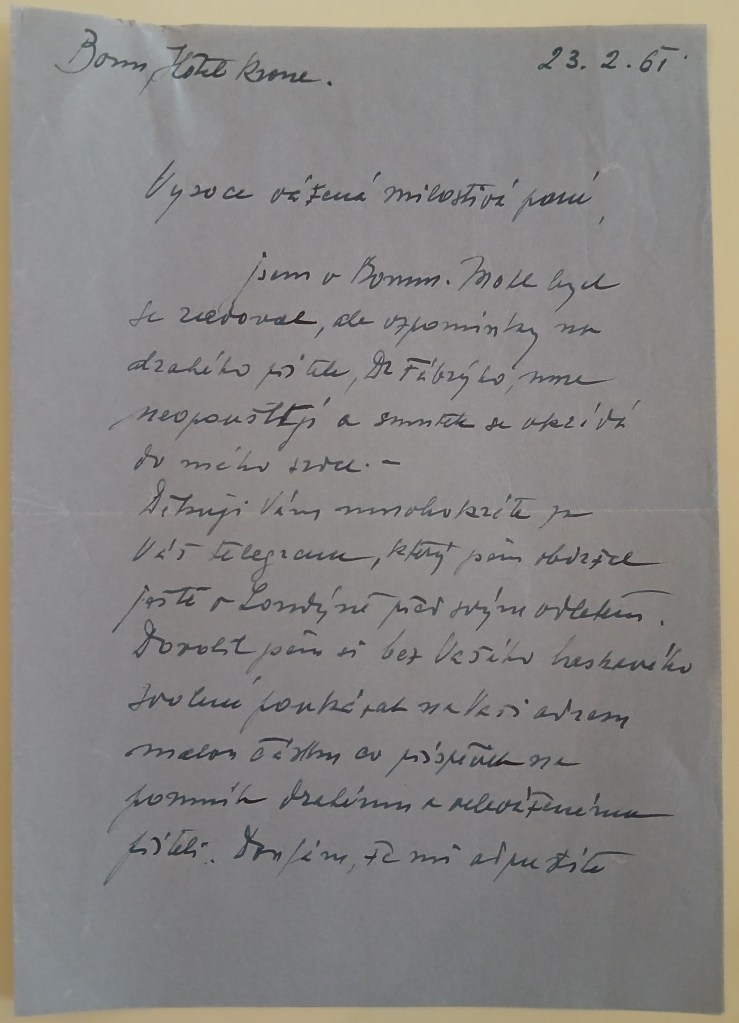

From Prchala to Madam Olga Fabry-Palka, 23 February 1961:

Bonn, Hotel Krone. 23.2.61

Dear Madam,

I am in Bonn. I could be happy, but the memories of my dear friend, Dr. Fabry, do not leave me and sadness returns to my heart.

Thank you very much for your telegram, which I received in London before my departure. Without your kind permission, I took the liberty of sending to your address a small sum as a contribution to the monument to a dear and esteemed friend. I hope you will forgive me and with a hand kiss I am

Yours faithfully

Prchala

Here is a unique letter from Dr. Samuel Bellus to Vlado’s sister Olga (Olinka) – he calls her ‘Olichka’ – sent 13 December 1960. At this time, Radio Free Europe became a European-based organization, it had been headquartered in New York.

13. December 1960

Dear Olichka,

Thank you very much for your letter. Don’t be angry that I didn’t get back to you sooner, but I really had a lot of work to do. A very turbulent time has passed us by. Ralph will surely tell you later.

Rudko and Fedor [Hodza] were here and we remembered you. Do you already know exactly when you will come here? Write me an appointment soon so I can relax. I would like to point out that I won’t be able to take even the shortest vacation, because I really can’t move away from Munich.

I will remember you at Christmas and I hope you remember me. Have a good time, Olichka.

Yours

Samuel

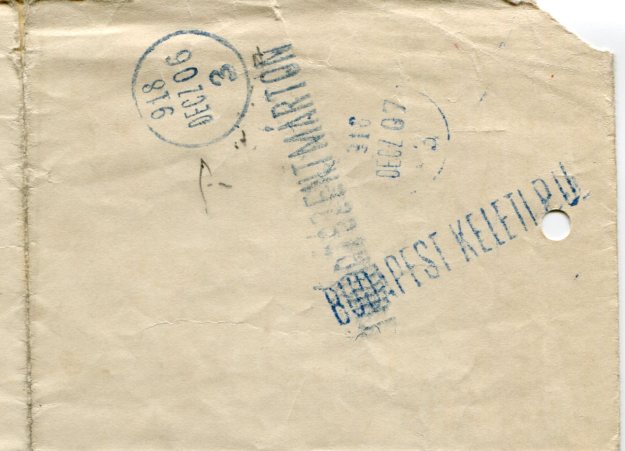

Envelopes found from Free Europe Committee, Two Park Avenue, New York 16, NY, sent to Dr. Pavel Fabry, in Geneva, Switzerland. Radio Free Europe was created through the efforts of the National Committee for a Free Europe, later known as Free Europe Committee, formed in New York by Allen Dulles who was head of the CIA. Until 1971, RFE was secretly funded by the CIA.

More details on Free Europe Committee history from Martin Nekola, Charles University in Prague:

“Looking back at the FEC as a shelter for prominent émigrés who used its resources and facilities to fight communism from abroad, the Committee can be considered a very unique organization with a specific role in the Cold War history. The number of people involved, the expenses incurred, and the efforts to get the FEC into the U.S. public awareness all serve as evidence of this. The émigrés relied on their “American friends” in the early Cold War years, believing in the possibility of defeating communism in Europe. However, after the failed Hungarian uprising in the fall 1956 that was violently suppressed by Soviet tanks, the mood among East-European exile communities dramatically changed. The émigrés realized that the West would not intervene directly in favor of an opposition group in a country within the Soviet sphere of influence. As a result, their expectations, along with the Free Europe Committee’s importance, gradually diminished.

Nevertheless, the legacy of the organization, sometimes called the “unofficial Department of U.S. propaganda” is not entirely forgotten. More than two decades after the fall of the Iron Curtain, Radio Free Europe still broadcasts in twenty-one countries, and Captive Nations Week—marked every year in July—serves as a reminder of the suffering of many nations still living in undemocratic conditions.”

The next document was first shared here on 30 April 2013, exactly 12 years ago today. From Dr. Samuel Bellus, a sworn statement on behalf of Mrs. OIga Viera Fabry-Palka (Vlado’s mother), 30 September 1956:

I, Samuel Bellus, of 339 East 58th Street, New York 22, New York, hereby state and depose as follows:

That this statement is being prepared by me at the request of Mrs. Olga Viera Fabry, nee Palka, who formerly resided in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, but since 1948 has become a political refugee and at present resides at 14, Chemin Thury, Geneva, Switzerland;

That I have known personally the said Mrs. Olga Viera Fabry and other members of her family and have maintained a close association with them since the year 1938, and that I had opportunity to observe directly, or obtain first hand information on, the events hereinafter referred to, relating to the persecution which Mrs. Olga Viera Fabry and the members of her family had to suffer at the hands of exponents of the Nazi regime;

That in connection with repeated arrests of her husband, the said Mrs. Fabry has been during the years 1939 – 1944 on several occasions subject to interrogations, examinations and searches, which were carried out in a brutal and inhumane manner by members of the police and of the “Sicherheitsdienst” [SD -TB] with the object of terrorizing and humiliating her;

That on a certain night on or about November 1940 Mrs. Fabry, together with other members of her family, was forcibly expelled and deported under police escort from her residence at 4 Haffner Street, Bratislava, where she was forced to leave behind all her personal belongings except one small suitcase with clothing;

That on or about January 1941 Mrs. Fabry was ordered to proceed to Bratislava and to wait in front of the entrance to her residence for further instructions, which latter order was repeated for several days in succession with the object of exposing Mrs. Fabry to the discomforts of standing long hours without protection from the intense cold weather and subjecting her to the shame of making a public show of her distress; and that during that time humiliating and derisive comments were made about her situation in public broadcasts;

That the constant fear, nervous tension and worry and the recurring shocks caused by the arrests and deportations to unknown destinations of her husband by exponents of the Nazi regime had seriously affected the health and well-being of Mrs. Fabry during the years 1939 – 1944, so that on several such occasions of increased strain she had to be placed under medical care to prevent a complete nervous breakdown; and

That the facts stated herein are true to the best of my knowledge and belief.

Samuel Bellus

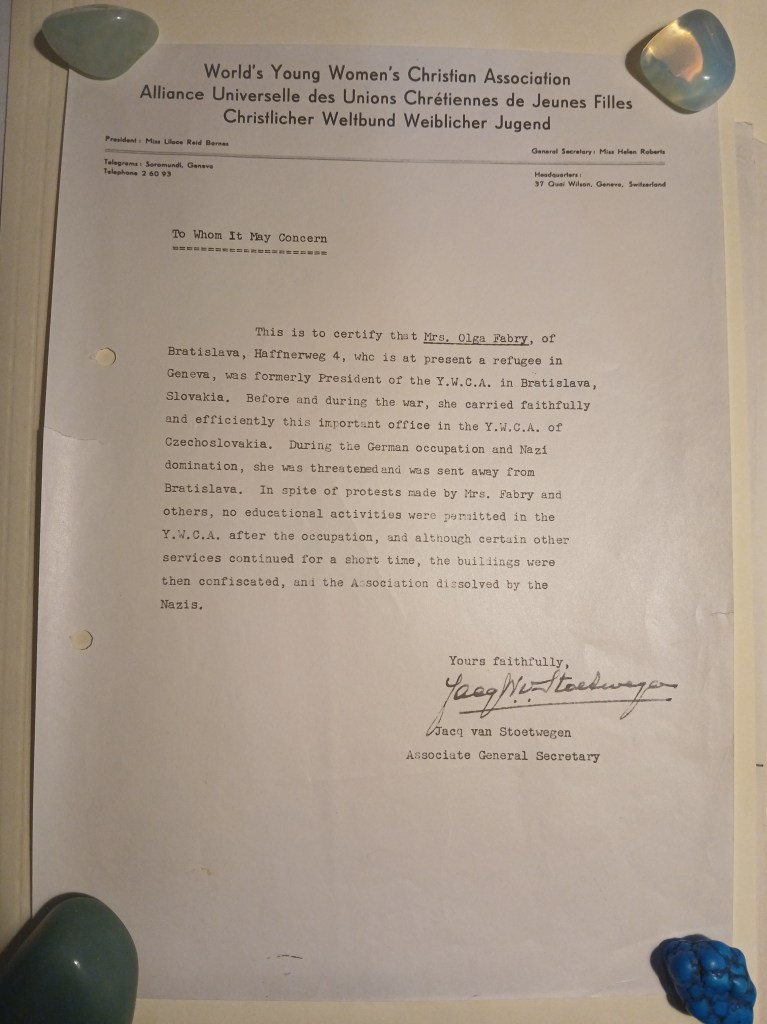

“To Whom It May Concern

This is to certify that Mrs. Olga Fabry, of Bratislava, Haffnerweg 4, who is at present a refugee in Geneva, was formerly President of the Y.W.C.A. in Bratislava, Slovakia. Before and during the war, she carried faithfully and efficiently this important office in the Y.W.C.A. in Czechoslovakia. During the German occupation and Nazi domination, she was threatened and was sent away from Bratislava. In spite of protests made by Mrs. Fabry and others, no educational activities were permitted in the Y.W.C.A after the occupation, and although certain other services continued for a short time, the buildings were then confiscated, and the Association dissolved by the Nazis.”

My name is Tara Burgett, I am an independent researcher and archivist, and the author of this blog dedicated to Vladimir “Vlado” Fabry. My husband, Victor, is the nephew of Vlado, the only child of Vlado’s sister, Olinka. When Olinka passed away in 2009, we discovered a trove of papers and photos stuffed in old suitcases in the house in New York; recognizing their importance, we packed them up and brought them to Washington state, and since then I have made it my mission to share the family story with the world.

When I first began my blog in 2013, the only information I could find on the internet about Vlado, other than the details of the plane crash in Ndola with Dag Hammarskjold, was a memoriam to one of Vlado’s girlfriends, Mary Sheila Dean Marshall; written by her son Chris Marshall. Here is the paragraph mentioning Vlado that made me laugh out loud:

“Sheila considered her time in New York to be some of the happiest days of her life. She roomed with her dearest friend, a gorgeous Czechoslovakian socialite named Desa Pavlu. The two of them must have left a trail of broken hearts throughout Manhattan. Sheila had a proposal of marriage from a young man named Arthur Gilkey. She declined, and shortly thereafter, he perished while ascending K2. Sheila was also courted by a chap named Vladimir “Vlado” Fabry. Vlado died with Dag Hammerskjold[sic] in The Congo[sic]. It seems that Vlado may have been connected with the CIA. Sheila said she could never see herself marrying Vlado because of his “very round bottom”.”

I was only a little annoyed that someone was using the words of one dead person to slag off another dead person, because it was just too funny to read about Vlado’s “very round bottom” on the internet. What did bother me though, was the statement from Mr. Marshall, that “Vlado may have been connected with the CIA”; which was just his opinion, when in fact, his father, Sheila’s husband Mike Marshall, was a CIA operative from 1952-1967.

The more time I spent reading and translating the letters and documents, the more I realized how important it was that I speak up for Vlado and his family. The Fabry family were the targets of intentional and malicious slander, in revenge for their fierce resistance to both Nazi and communist invasions of Czechoslovakia, and sharing their archive has been my way of setting the record straight.

Vlado studied Law and Political Science at Comenius University in Bratislava, following in the footsteps of his father, Pavel Fabry, who was also a lawyer. Before joining the United Nations Legal Department in 1946, Vlado served as Personal Secretary to the Minister of Commerce in Prague. Vlado and his father were both very romantic and unconventional characters, who loved music, poetry, travel, and all kinds of adventure; they were not afraid to stand up for their beliefs, even in the face of danger and threats of death.

After the communist coup d’etat in 1948, the whole family were forced to flee Czechoslovakia, and lived as political refugees in Switzerland. Vlado was often on the move, working for the UN in many countries, including New Zealand, Indonesia, Ghana, Egypt, and Congo, but he would stay with his parents in Geneva whenever he was on leave, at 14 Chemin Thury.

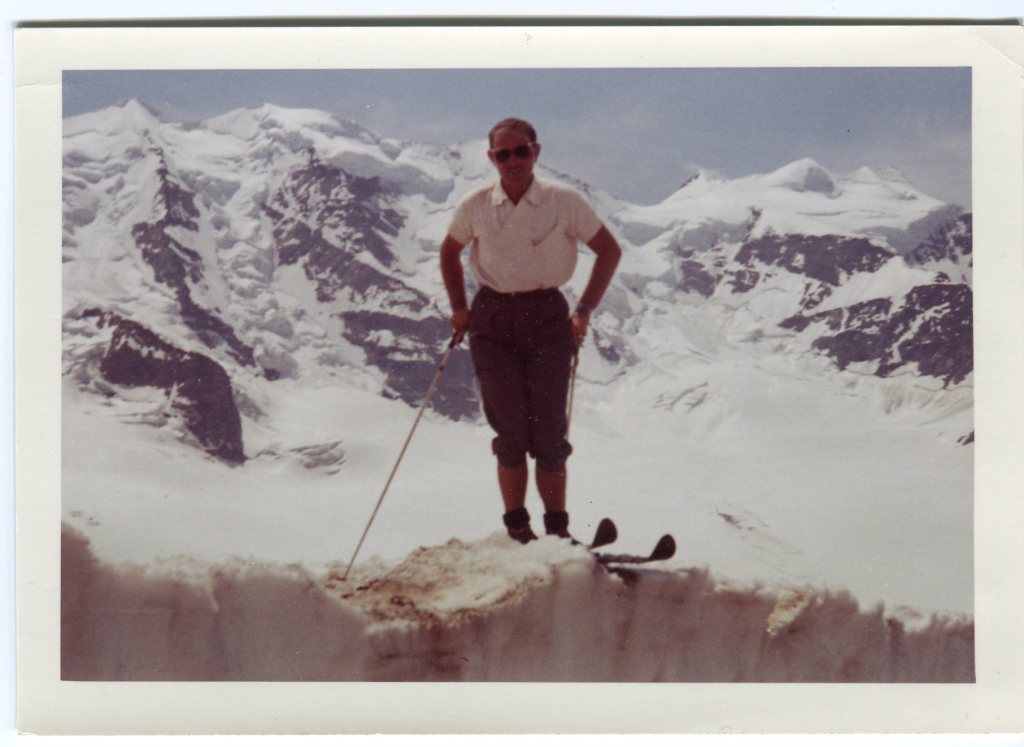

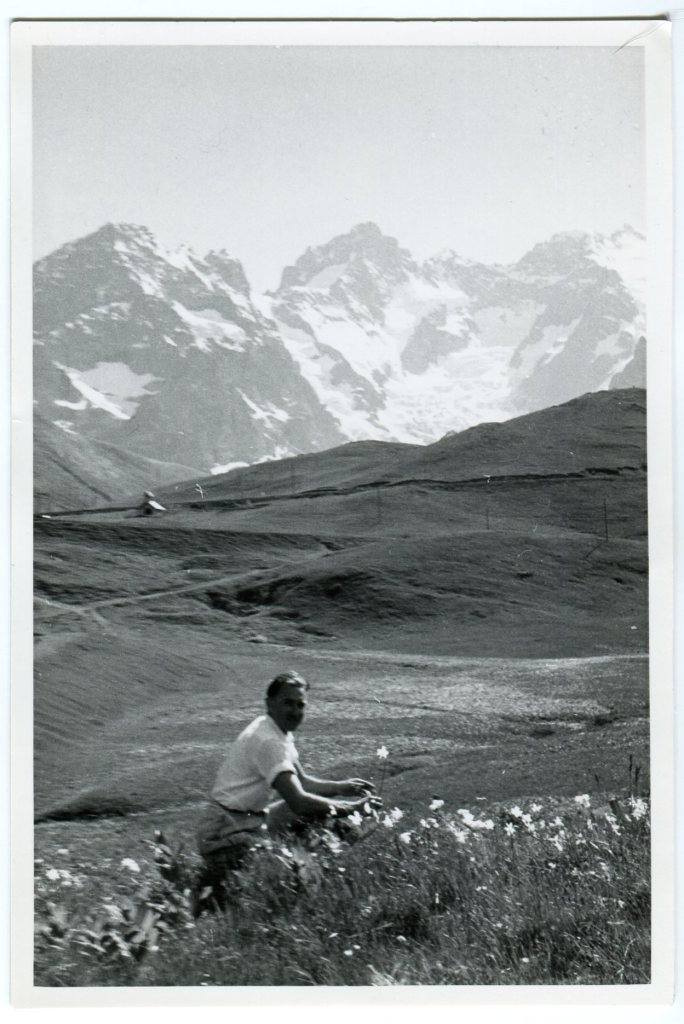

Vlado was loved by many of his colleagues at the UN, for his kindness and hospitality, and for his enthusiasm for skiing, mountain climbing, as well as his intellect and charm.

I could say more about his personality, but I feel the letters Vlado left behind, and the letters of his friends and family who knew him, say it best. He was an example of courage that anyone who knew him tried to follow, and is an inspiration to me, personally.

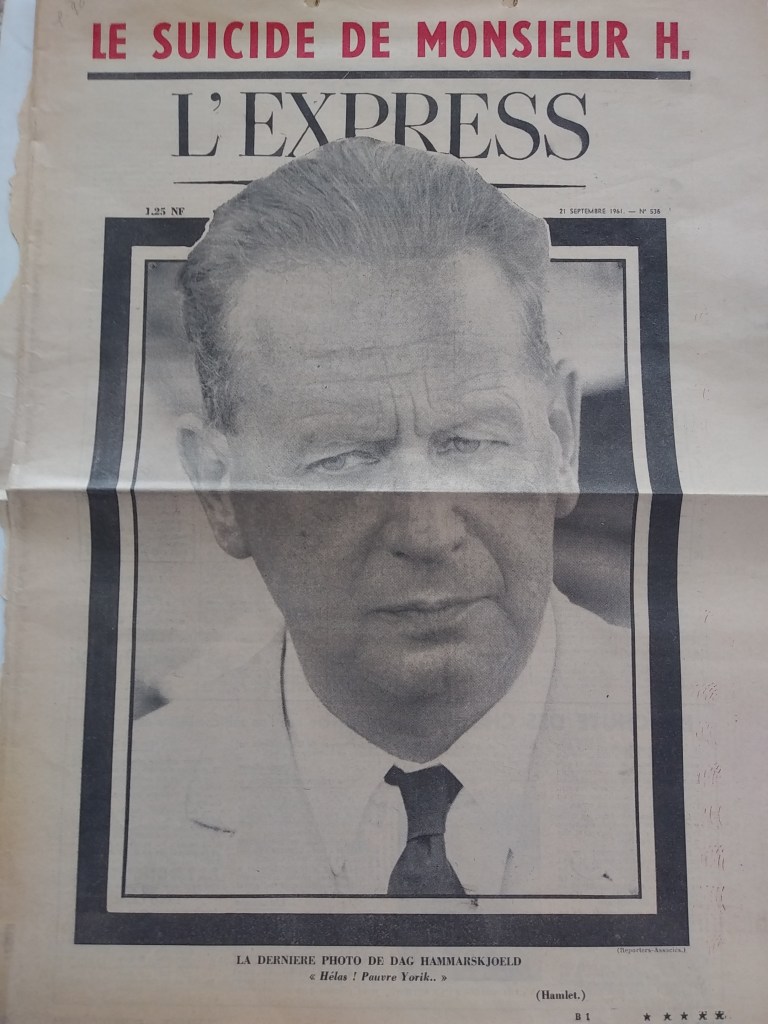

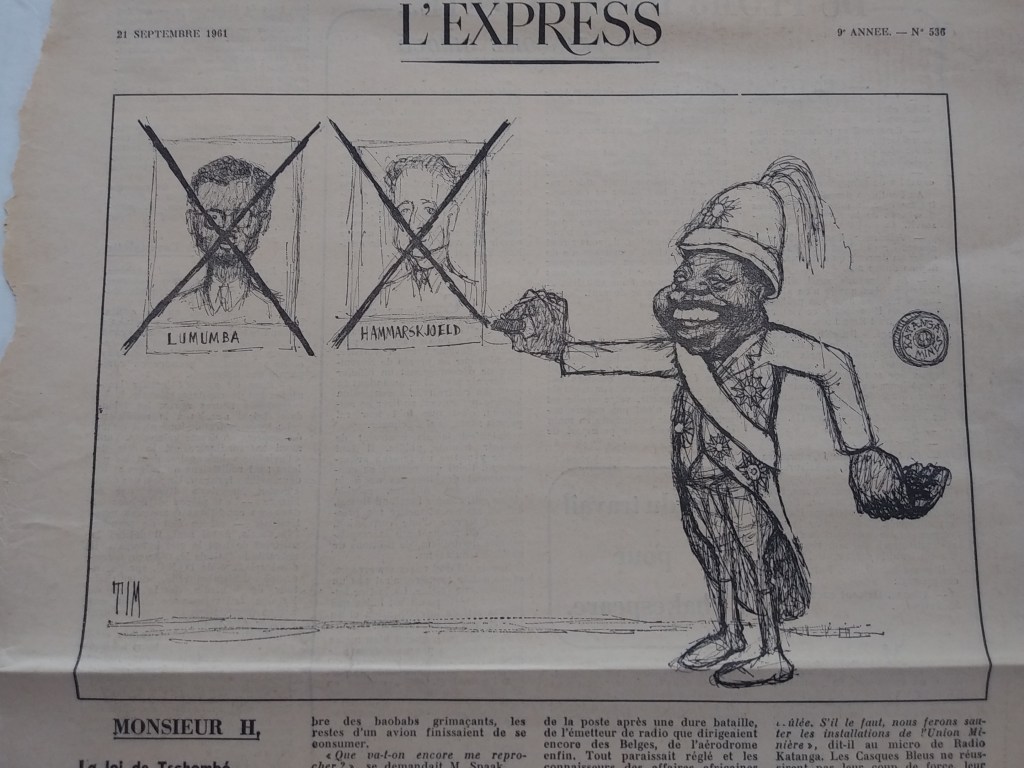

I was hesitant to share this here, because of the editorial choice of the word “suicide” to describe the death of Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold, but it is important because this was saved in a collection of other international papers by Olinka and Olga Fabry. The political cartoon, showing Moïse Tshombe collecting his money from the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga mines with the murders of Patrice Lumumba and Hammarskjold, is gruesome but on point. From our personal coin collection, not from the Fabry archive, I have also included scans of two coins from Katanga from 1961.

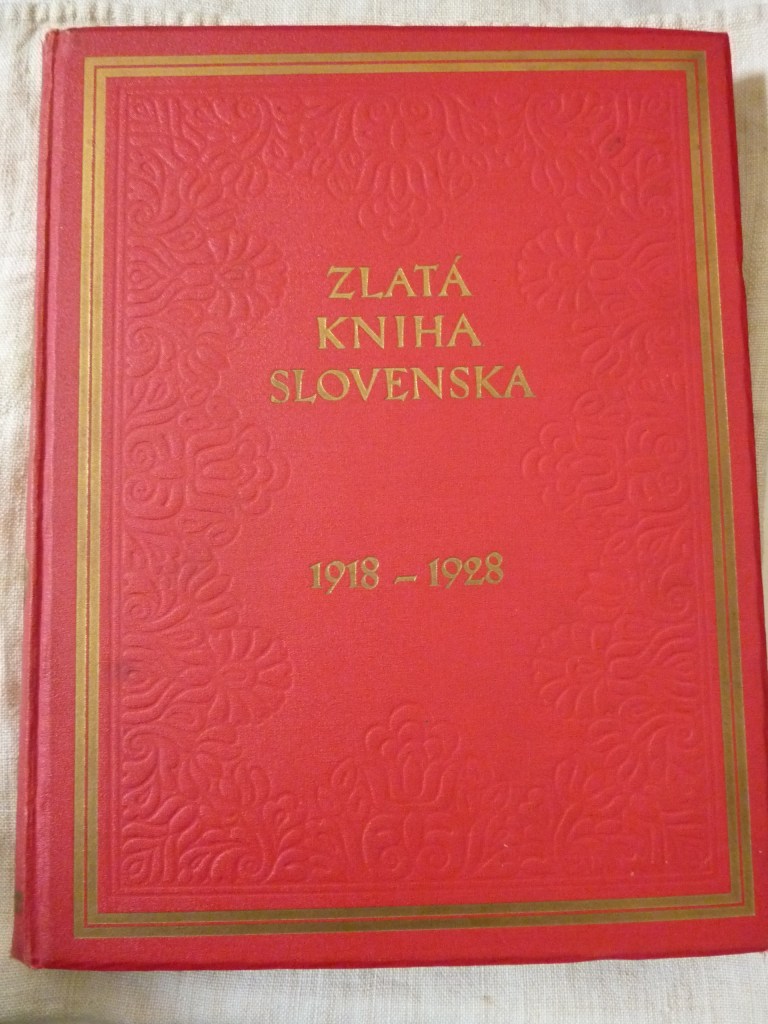

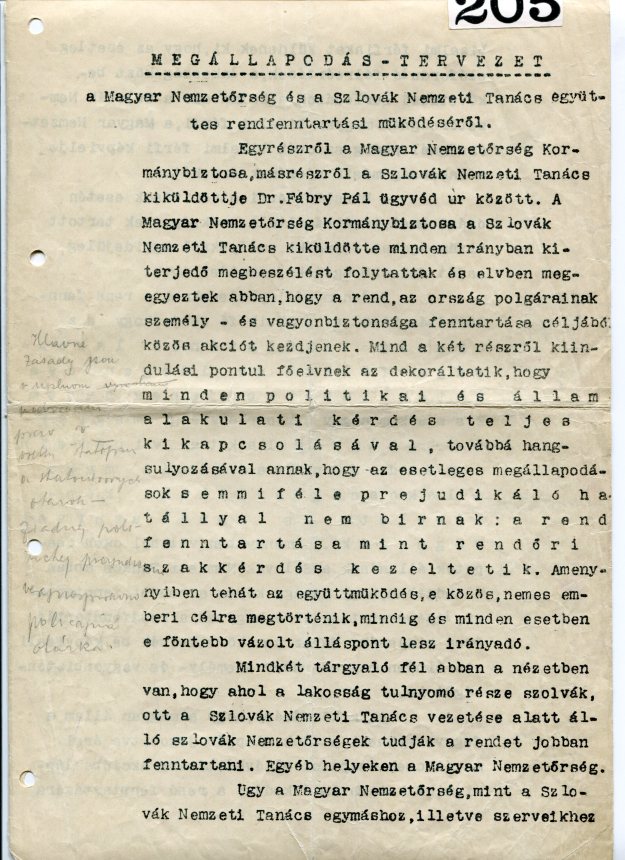

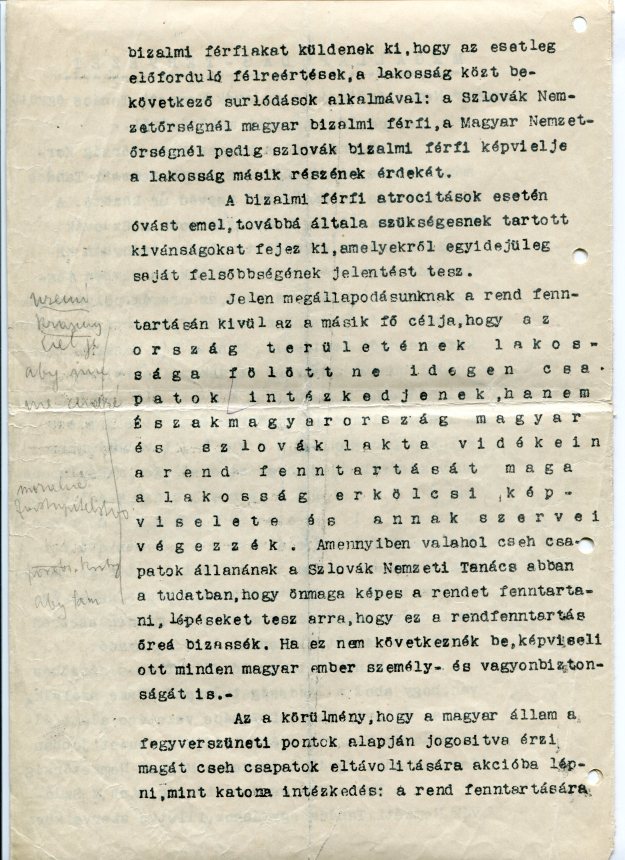

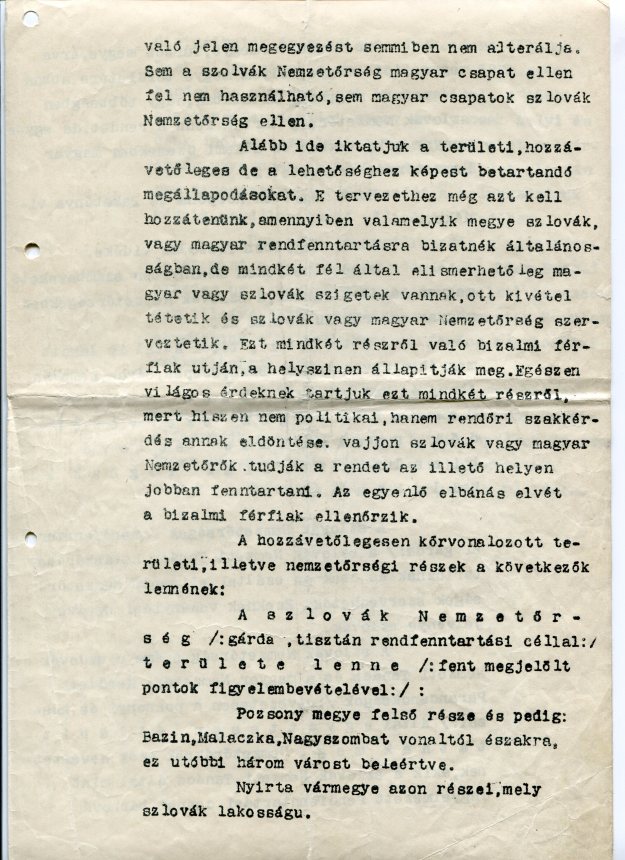

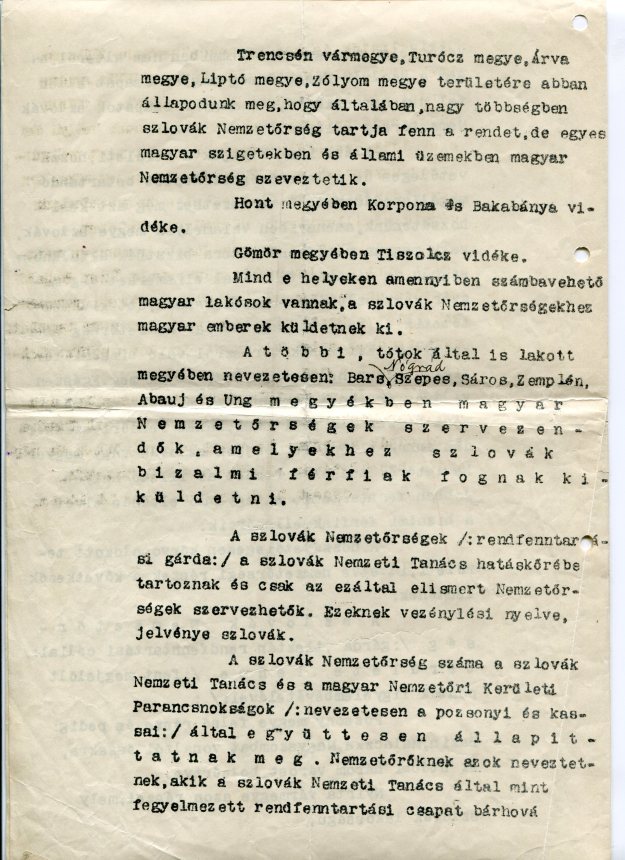

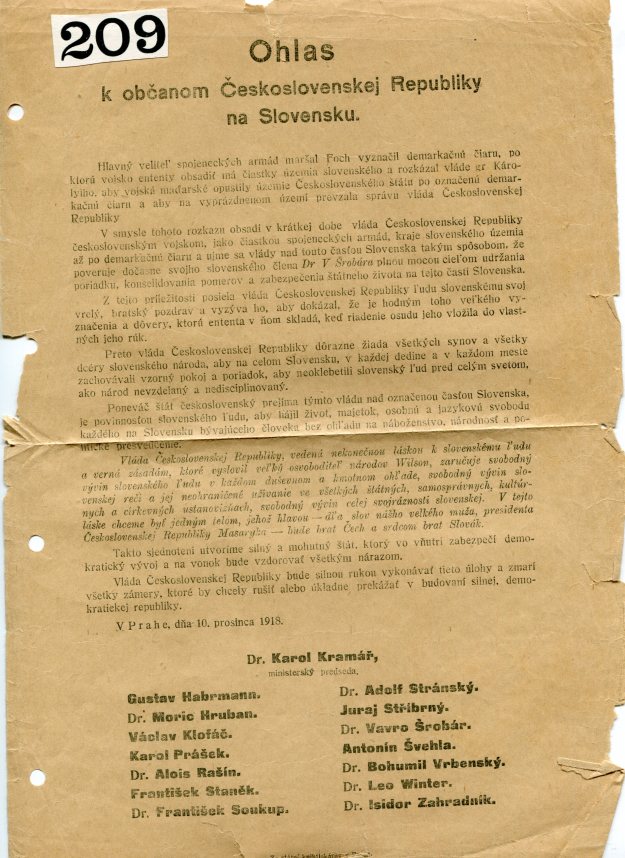

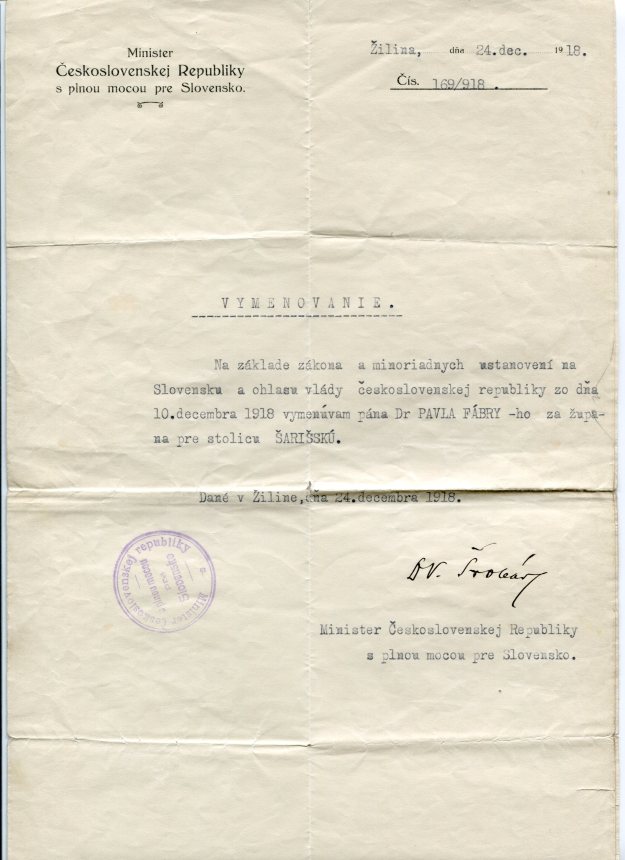

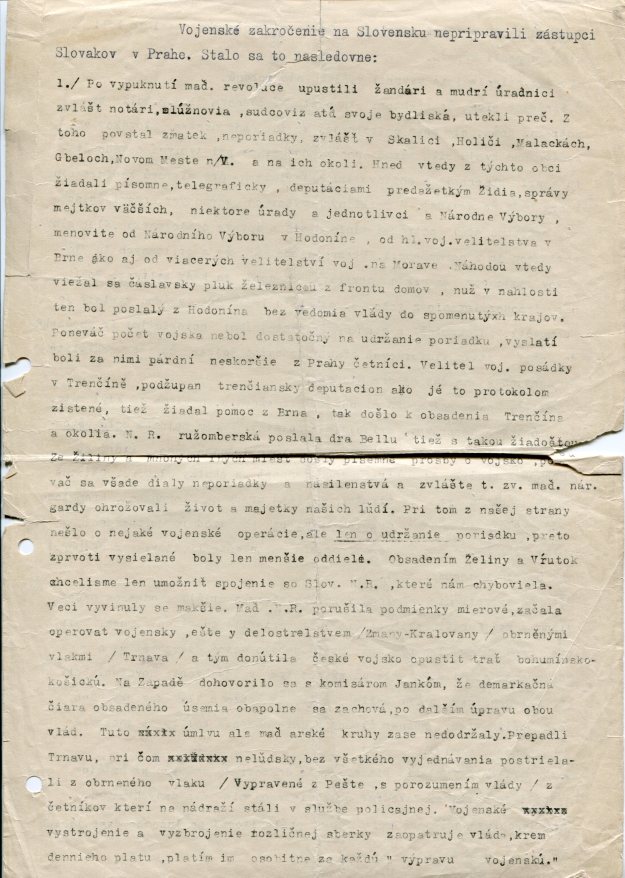

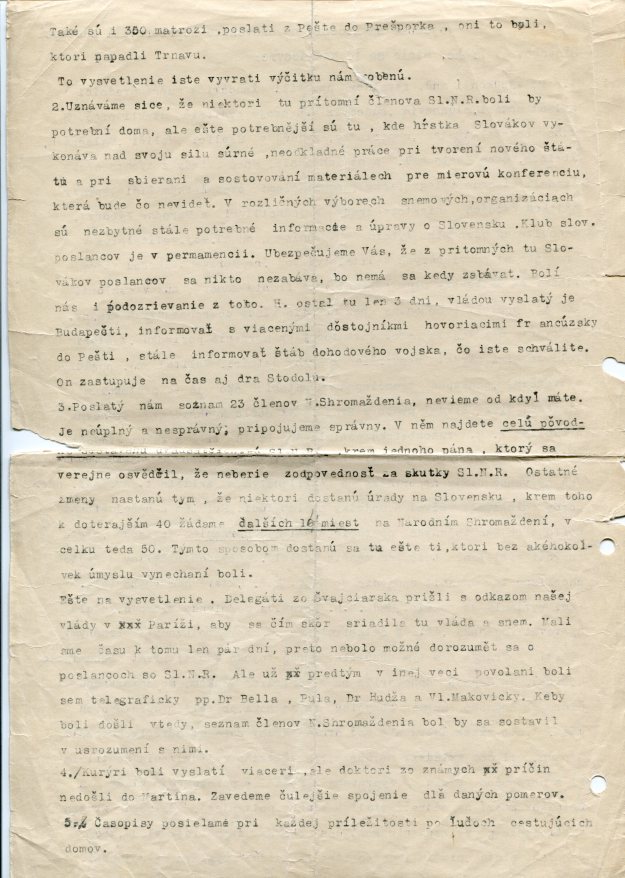

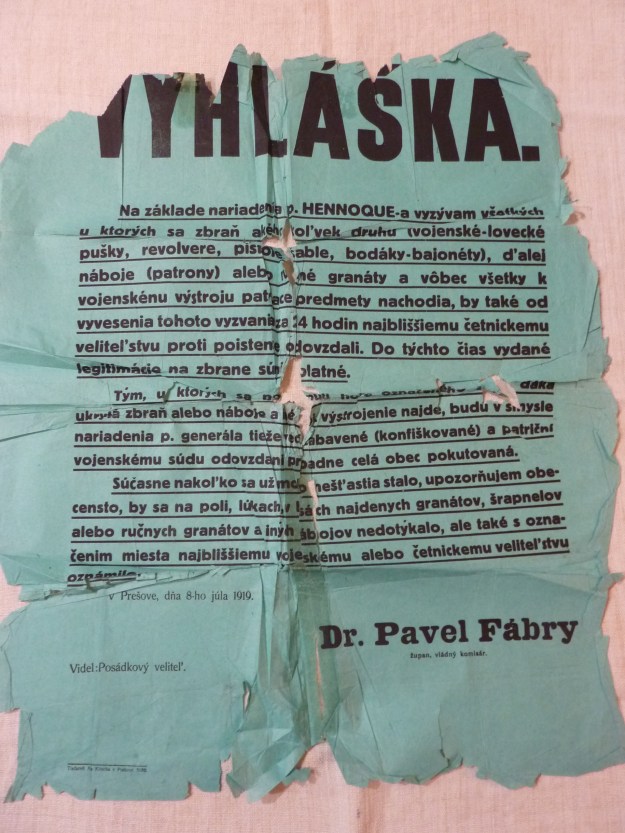

The following documents and photos are from November 1918 to December 1920, they are in Hungarian and I am not able to translate them – I will return later to transcribe some of these. I hope to give a clearer picture of why Pavel Fabry, and his family, were the target of retaliation and revenge by Hungary and Russia, and why Russia still occupies our home in Bratislava – the house belongs to the city of Bratislava now, my husband and I donated it!

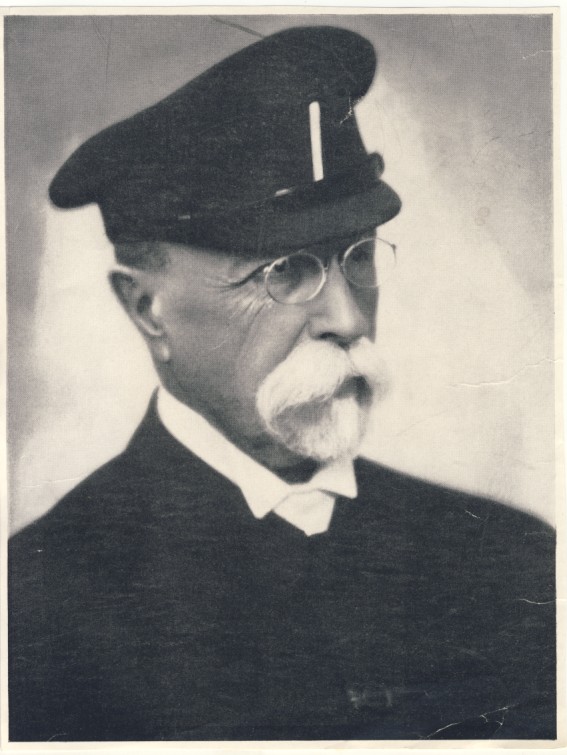

For historical context, the First Czechoslovak Republic began on 28 October 1918, and the boundaries and government were established with the Czechoslovak Constitution of 29 February 1920. The Treaty of Trianon was signed on 4 June 1920, and Saris County became part of newly formed Czechoslovakia; Saris was formerly known as Saros, a County of the Kingdom of Hungary, and had been since the 13th century – Pavel was Governor of Presov and prefect of Saris at its very beginning! In connection, this pdf text from the University of Presov was sent to me by a very helpful family relative last year(thank you!!): “Eastern Slovakia in 19th and 20th centuries in relation of the centre and periphery“; she wrote that “it describes the installation and the very beginning of [Pavel’s] governance in Presov.”

Our grandfather Pavel “Tata/Tatusko” Fabry, sharing his love of photography with his son, Vladimir “Vlado” Fabry; circa 1920s.

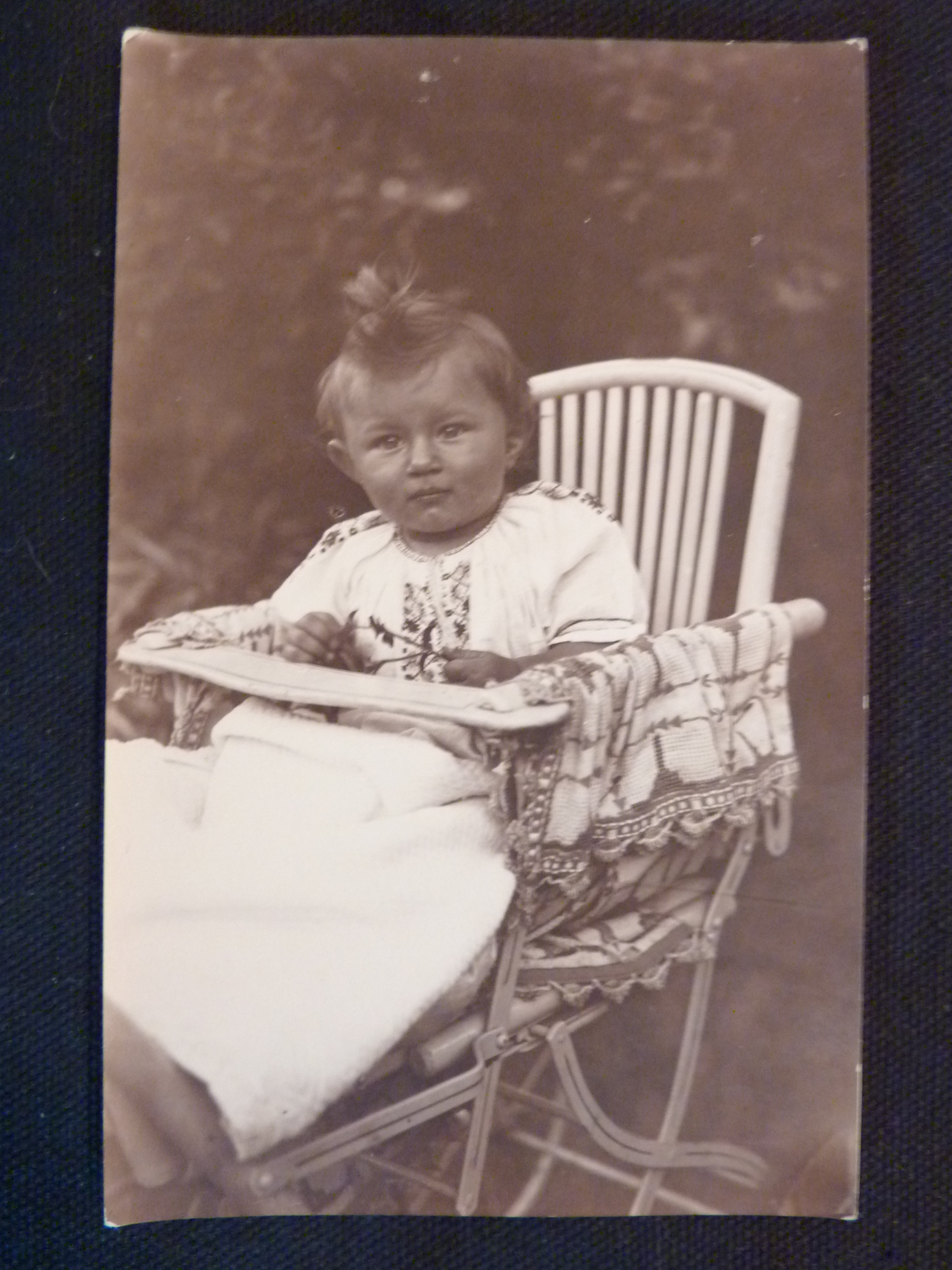

Baby Vlado held by unidentified person, with “Maminka”, our grandmother Olga Fabry-Palka. Vlado was born on 23 November 1920, in Liptovský svätý mikuláš, Czechoslovakia.

Baby Vlado – those ears!

Vlado having a nap.

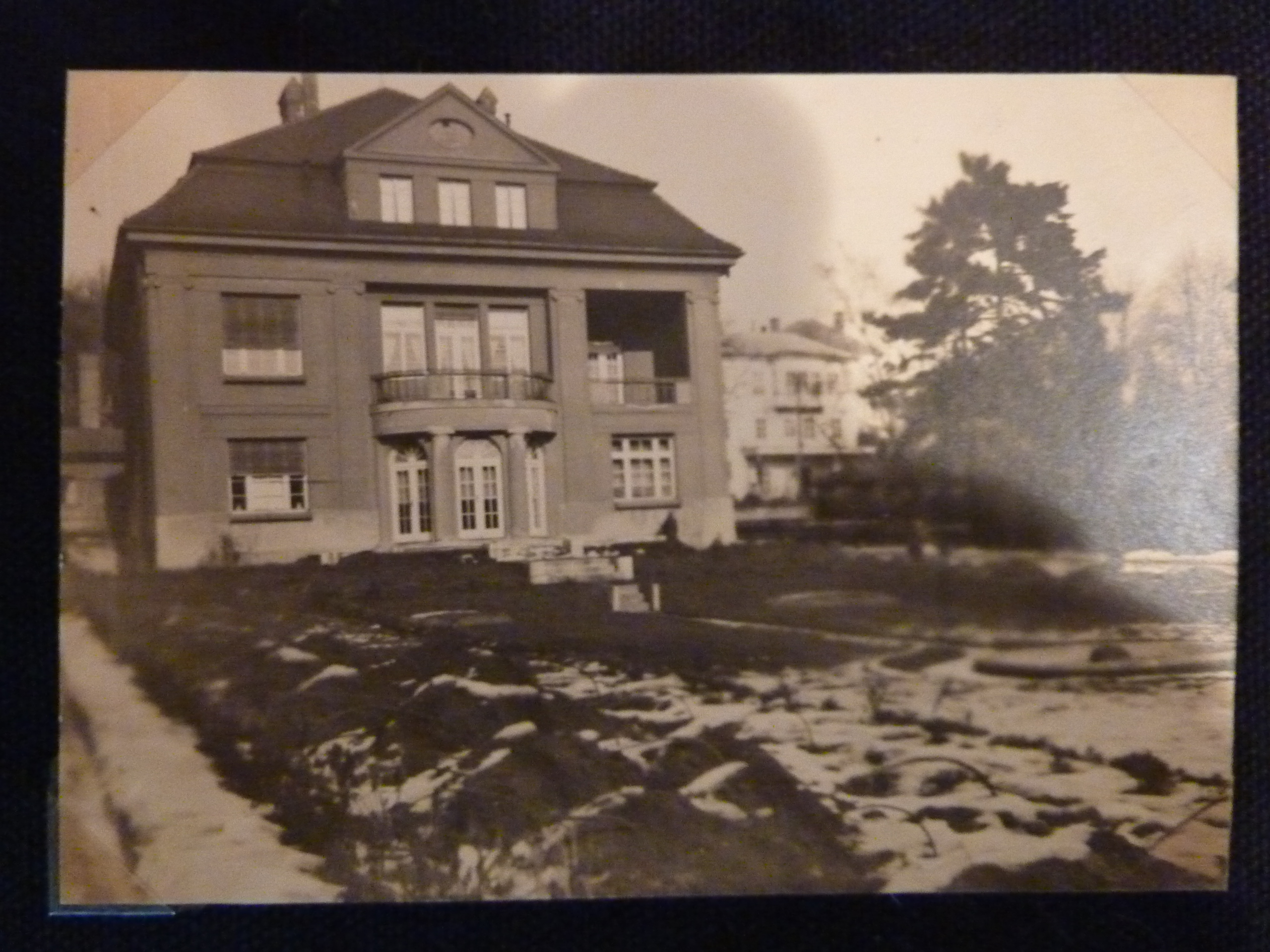

Vlado’s only sibling, sister Olga “Olinka”, arrives home; she was born 5 October 1927, in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. Their mother, Olga Fabry-Palka, on far right, dressed in black; brother Vlado is on the left, wearing knee socks and black buckled shoes. This photo, and the rest that follow, show the home our family built in Bratislava – it was seized by the Communists in the coup d’état of 1948, handed over as a gift to Russia, and has ever since been occupied as their embassy. You can see recent photos of our home by searching for “Russian Embassy Bratislava”.

Olinka and Vlado with a nanny.

Maminka, Vlado and Olinka playing in the garden.

Olinka with Tatusko.

Admiring the long stemmed roses that Maminka planted.

This photo, and the two following, were taken around 1930.

Olinka with a friend, Maminka in background.

Mother and daughter, so happy!

These two photos are undated, but it looks like Vlado got what he wanted for his birthday! I’m so glad that these photos were saved, but some of them have curled from improper storage. The American Library Association(ALA) website has advice here, for those of you wondering how to safely flatten your old photos.

Bambi! This was Vlado and Olinka’s pet deer – Olinka told us the story about their deer, that it jumped the fence and crashed the neighbor’s wedding party, eating all the cake – and then the police were chasing it all over town!

Olinka and friend.

Pavel Fabry very likely colorized these photos with his set of Caran d’Ache pencils, some of which we are still using! Dated July 1927.

Vlado and his sister had pretty much the same haircut for a while, but this is Vlado on the stairs.

Marked on back “rodina Fabry v Bratislava” – Fabry family in Bratislava. I recognize Olga Fabry-Palka and her mother, but I am unable to identify the others at this time. The next few photos, showing guests visiting the house, are unmarked – help with identification is appreciated!

Here is one of Vlado, the hat and beard don’t disguise!

Pavel, Vlado, Olga, and Olinka, and a chocolate cake, in the dining room.

Vlado with unidentified guests, waiting for cake!

The family all together!

There are more photos, but first, here are important documents which tell the story of our family and home in Bratislava:

Drafts of Pavel Fabry’s Curriculum Vitae, 11 September 1952, printed here:

“Pavel Svetozar FABRY, LLD, was born on January 14th, 1891 of an old family of industrialists and businessmen. After graduating in business administration, he studied law, attaining the degree of Doctor of Law; passed the bar examinations; and successfully completed the examinations required to qualify for judgeship.

During World-War-I, Mr. Fabry served as officer in an artillery division as well as in the service of the Army’s Judge Advocate-General. He became the first Secretary of the Provisional National Council established to prepare the liberation of Slovakia and the orderly transfer of its administration to the Czechoslovak Government. After the foundation of the Czechoslovak Republic, he was appointed Prefect (chief Government official) for the Eastern part of Slovakia.

When the Communist armies of the Hungarian Government of Bela Kun attacked Slovakia in 1919, Mr. Fabry was named High Commissioner Plenipotentiary for the defense of Eastern Slovakia. In this function he was entrusted with the co-ordination of the civil administration with the military actions of the Czechoslovak Army and of the Allied Military Command of General Mittelhauser. His determined and successful effort to prevent Eastern Slovakia to fall under the domination of Communist Armies – the victorious results of which contributed to the fall of the Communist regime in Hungary – drew on Mr. Fabry the wrath of the Communist leaders; they declared him the “mortal enemy of the people”, led violent press campaigns against him and attacked him overtly and covertly continually and at every opportunity.

After the consolidation of the administrative and political situation of Slovakia, Mr. Fabry left the Government service and returned to his private practice as barrister. He specialized in corporation law and his assistance was instrumental in the founding and expansion of a number of industrial enterprises. He became Chairman or one of the Directors of Trade Associations of several industrial sectors, particularly those concerned with the production of sugar, alcohol, malt and beer. He was elected Chairman of the Economic Committee of the Federation of Industries, and played the leading role in several other organizations. He also was accredited as Counsel to the International Arbitration Tribunal in Paris.

Among civic functions, Mr. Fabry devoted his services particularly to Church, acting as Inspector (lay-head) of his local parish and as member of the Executive Committee of the Lutheran Church of Czechoslovakia. His appointment as delegate to the World Council of Churches’ meeting in Amsterdam in 1948 prompted his arrest by the Communist Government.

Although Mr. Fabry never stood for political office nor for any political party function, he was well known for his democratic and liberal convictions, and for the defense of these principles whenever his activities gave him the opportunity to do so. He earned himself a reputation in this respect which brought him the enmity of the adversaries of democracy from both the right and the left. He became one of the first Slovaks to be sent to a concentration camp following the establishment of a Pro-German fascist regime in 1939. His release could later be arranged and he was able to take active part in the underground resistance movement against the occupant; for this activity the German secret police (Gestapo) ordered his pursuit and execution in 1945, but he was able to escape the death sentence. In spite of his resistance record (or perhaps because of it), Mr. Fabry was among those arrested by the Russian Army, on the instigation of the Communist Party which could not forget his anti-Communist activities dating back all the way to 1919. Due to pressure of public opinion Mr. Fabry’s imprisonment at that time was very short; but when Communist seized power in Czechoslovakia in 1948, they did not miss the opportunity to settle accounts with him. He was removed from all his offices, his property was confiscated, he was imprisoned and subjected to a third degree cross-examination taking six months. No confessions of an admission which could have served as a basis for the formulation of an accusation could, however, be elicited from Mr. Fabry, and he managed to escape from the prison hospital where he was recovering from injuries inflicted during the examination. He succeeded to reach Switzerland in January 1949, where he has continued in his economic activities as member of the Board of Directors, and later President, of an enterprise for the development of new technologies in the field of bottling and food conservation. He was also active in assisting refugees and was appointed as member of the Czechoslovak National Council-in-exile.”

And this, from the September 25, 1961 Congressional Record: “Extension of Remarks of Hon. William W. Scranton of Pennsylvania in the House of Representatives”:

“Mr. SCRANTON. Mr. Speaker, in the tragic air crash in which the world lost the life of Dag Hammarskjold, we also suffered the loss of the life of Dr. Vladimir Fabry, the legal adviser to the United Nations operations in the Congo.

In the following statement by John C. Sciranka, a prominent American Slovak journalist, many of Dr. Fabry’s and his esteemed father’s attributes and good deeds are described. Dr. Fabry’s death is a great loss not only for all Slovaks, but for the whole free world.

Mr Sciranka’s statement follows:

Governor Fabry (Dr. Fabry’s father) was born in Turciansky sv. Martin, known as the cultural center of Slovakia. The Communists dropped the prefix svaty (saint) and call the city only Martin.

The late assistant to Secretary General Hammarskjold, Dr. Vladimir Fabry, inherited his legal talents from his father who studied law in the law school at Banska Stavnica, Budapest, and Berlin. The old Governor before the creation of Czechoslovakia fought for the rights of the Slovak nation during the Austro-Hungarian regime and was imprisoned on several occasions. His first experience as an agitator for Slovak independence proved costly during his student days when he was arrested for advocating freedom for his nation. Later the military officials arrested him on August 7, 1914, for advocating a higher institute of education for the Slovakian youth in Moravia. This act kept him away from the front and held him back as clerk of the Bratislava court.

He was well equipped to aid the founders of the first Republic of Czechoslovakia, which was created on American soil under the guidance and aid of the late President Woodrow Wilson. After the creation of the new republic he was made Governor (zupan) of the County of Saris, from which came the first Slovak pioneers to this city and county. Here he was confronted with the notorious Communist Bela Kun, who made desperate efforts to get control of Czechoslovakia. This successful career of elder Governor Fabry was followed by elevation as federal commissioner of the city of Kosice in eastern Slovakia.

But soon he resigned this post and opened a law office in Bratislava, with a branch office in Paris and Switzerland. The Governor’s experience at the international court gave a good start to his son Vladimir, who followed in the footsteps of his father. During World War II the elder Fabry was imprisoned by the Nazi regime and young Vladimir was an underground resistance fighter.

Dr. Vladimir Fabry, 40-year-old legal adviser to Secretary Dag Hammarskjold with the United Nations operation in Congo, who perished in the air tragedy, was born in Liptovsky Svaty Mikulas Slovakia. He received his doctor’s degree in law and political science from the Slovak University in Bratislava in 1942 and was admitted to the bar the following year. He was called to the United Nations Secretariat in 1946 by his famous countryman and statesman, Dr. Ivan Kerno, who died last winter in New York City after a successful career as international lawyer and diplomat and who served with the United Nations since its inception. Dr. Vladimir Fabry helped to organize postwar Czechoslovakia. His family left the country after the Communist putsch in February 1948. His sister Olga is also in the service of the United Nations in New York City [as a Librarian.-T]. His father, the former Governor, died during a visit to Berlin before his 70th birthday, which the family was planning to celebrate on January 14, 1961, in Geneva.

Before going to the Congo in February, Dr. Fabry had been for a year and a half the legal and political adviser with the United Nations Emergency Force in the Middle East. In 1948, he was appointed legal officer with the Security Council’s Good Offices Committee on the Indonesian question. He later helped prepare legal studies for a Jordan Valley development proposal. He also participated in the organization of the International Atomic Energy Agency. After serving with the staff that conducted the United Nations Togaland plebiscite in 1956, he was detailed to the Suez Canal clearance operation, winning a commendation for his service.

Dr. Vladimir Fabry became a U.S. citizen 2 years ago. He was proud of his Slovak heritage, considering the fact that his father served his clerkship with such famous Slovak statesmen as Paul Mudron, Andrew Halasa, Jan Vanovic, and Jan Rumann, who played important roles in modern Slovak history.

American Slovaks mourn his tragic death and they find consolation only in the fact that he worked with, and died for the preservation of world peace and democracy with such great a leader as the late Dag Hammarskjold.”

The C.V. of Pavel Fabry from 17 December 1955, which I translated a while back; the letterhead on this first page is from the Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany, Geneva.

This is the C.V. of our grandmother Olga Fabry, which I have not yet translated. The following statement was made on her behalf, from 30 November 1956:

“I, Samuel Bellus, of 339 East 58th Street, New York 22, New York, hereby state and depose as follows:

That this statement is being prepared by me at the request of Mrs. Olga Viera Fabry, nee Palka, who formerly resided in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, but since 1948 has become a political refugee and at present resides at 14, Chemin Thury, Geneva, Switzerland;

That I have known personally the said Mrs. Olga Viera Fabry and other members of her family and have maintained a close association with them since the year 1938, and that I had opportunity to observe directly, or obtain first hand information on, the events hereinafter referred to, relating to the persecution which Mrs. Olga Viera Fabry and the members of her family had to suffer at the hands of exponents of the Nazi regime;

That in connection with repeated arrests of her husband, the said Mrs. Fabry has been during the years 1939 – 1944 on several occasions subject to interrogations, examinations and searches, which were carried out in a brutal and inhumane manner by members of the police and of the “Sicherheitsdienst” with the object of terrorizing and humiliating her;

That on a certain night on or about November 1940 Mrs. Fabry, together with other members of her family, was forcibly expelled and deported under police escort from her residence at 4 Haffner Street, Bratislava, where she was forced to leave behind all her personal belongings except one small suitcase with clothing;

That on or about January 1941 Mrs. Fabry was ordered to proceed to Bratislava and to wait in front of the entrance to her residence for further instructions, which latter order was repeated for several days in succession with the object of exposing Mrs. Fabry to the discomforts of standing long hours without protection from the intense cold weather and subjecting her to the shame of making a public show of her distress; and that during that time humiliating and derisive comments were made about her situation in public broadcasts;

That the constant fear, nervous tension and worry and the recurring shocks caused by the arrests and deportations to unknown destinations of her husband by exponents of the Nazi regime had seriously affected the health and well-being of Mrs. Fabry during the years 1939 – 1944, so that on several such occasions of increased strain she had to be placed under medical care to prevent a complete nervous breakdown; and

That the facts stated herein are true to the best of my knowledge and belief.”

The first page of Pavel’s C.V., 1955.

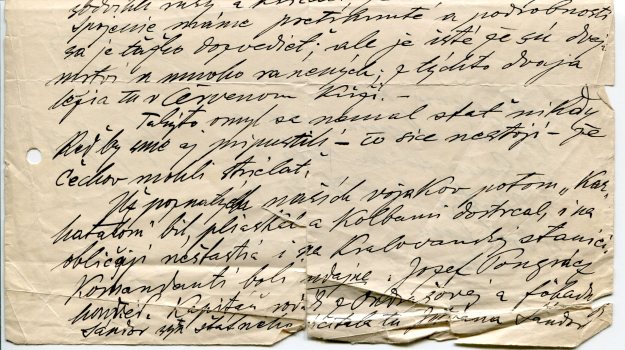

This is my translation of the last three pages of Pavel’s C.V., pages 11-13, with photos included to compare and help improve the translation:

“After the Persecution Today

“As the so-called Russian Liberation Army in Slovakia – consuming (raubend) more than liberating – invaded our city, I was immediately arrested and led into the basement of the NKVD, where I found quite a few others arrested. The public, especially the workers in awareness that I freed from deportation a few days before, chose to stand up and with the deputation of workers demanded the immediate release from liability. But the commander of the NKVD also had the deputation arrested and had me lead them into the cellar. The workers union had accumulated in front of the Villa and vigorously demanded the release from liability, whereupon the commander turned to the High command in Kosice, whereupon we were released – seven and a few, but the rest were to be deported to Siberia. The NKVD commander later said I was arrested on the basis of the request of the Hungarian Communists, because I, as High Commissioner in 1919, acted so harshly (so schroff) against the troops of Bela Kun. And he said that if I was released now, I would not be spared Siberia.

The public had reacted sharply. I immediately became an honorary citizen of the circle and an honorary member of the National Committee, elected unanimously, and I was given the two highest honors.

The spontaneous demonstrations of the public gave me the strength to forcefully intervene against many attacks, and also to help my fellow Germans and give confirmation that they behaved decently during the Hitler era, and to stifle all individual personal attacks of vengeance in the bud. As I have already mentioned, I was able to help the internees that they not go to the Soviet zone, as was planned, but were sent to West Germany and Austria. I was a daily visitor to collection centers and in prisons, to help where help was justified.”

“My parlous state of health has not allowed me to carry my work further. The law firm I have has only a limited representation of associates, and these are only my best performing workers.

After the Communist coup performed by Russian Deputy Foreign Minister [Valerian] Zorin for the Communists, the time is broken up with invoices to settle for my work against Communism as High Commissioner in 1919. And on the instructions of the insulted Mátyás Rákosi I was first of all relieved of all my functions and representatives, and subjected to all possible harassment, interrogations, etc. When I went to the delegation, as elected President of the Financial and Economic Committee of the General Assembly of the World Council of Churches, in Amsterdam, and was asked for my passport, I was arrested on the pretext of excessive imaginary charges. My whole fortune was taken, all accounts were confiscated and my Villa locked with furnishings, clothes, supplies, and everything, since it was the Consul-General of Russia; and on the same evening I was arrested as a “National Gift”, the nation was taken over, and in the night the Russians transferred the land register.

And so, my health still shattered by the persecution these Nazi monsters caused, they transferred me to the locked section of the hospital to make interrogations there. After seven months detention [In another document it says only 6 months, which I will include here, after this testimony.-T] the workers and employees of some companies succeeded to liberate me in the night on January 21-22, 1949, and led me to a kamion near the border. I had foreseen that the police would know about my escape during the night, and that’s why I escaped (uberschreitete ?) to the Hungarian border with Austria, and again by the Austrian border, since I was immediately searched with many dogs.

I managed with the help of my friends to leave the Soviet zone disguised, and made it to Switzerland where I anticipated my wife and daughter. [I have an audio recording of Olga Fabry, Pavel’s daughter, where she says that her father escaped from the prison hospital dressed as a nun, and made it across the Swiss border by train, hiding inside a beer barrel.-T]

The Swiss authorities immediately received me as a political refugee and assured me of asylum, and issued all the necessary travel documents.”

“To this day I am constantly witness to the most amiable concessions by the Swiss authorities.

In my description of illness, my activity in Switzerland is already cited.

Accustomed to the work of life, and since my health no longer permits regular employment, I have adopted the assistance of refugees. Since Geneva was the center of the most important refugee organizations, I was flooded with requests by the refugees of Western Europe.

I took part on the board of the Refugee Committee in Zurich and Austria, after most refugees came from Slovakia to Austria, and I had to check very carefully if there were any refugees that had been disguised. I was then elected as President of the Refugee Committee, but on the advice of the doctors treating me I had to adjust this activity, because through this work my health did not improve. Nevertheless, I succeeded in helping assist 1200 refugees in the decisive path of new existence.

Otherwise, I remain active in the Church organizations. All this human activity I naturally consider to be honorary work, and for this and for travel I never asked for a centime.

Since I am more than 62 years old, all my attempts to find international employment failed, because regulations prohibit taking on an employee at my age. It was the same case with domestic institutions.

My profession as a lawyer I can exercise nowhere, since at my age nostrification of law diplomas was not permitted. To start a business or involvement I lacked the necessary capital – since I have lost everything after my arrests by the Communists, what had remained from the persecution.

And so I expect at least the compensation for my damages in accordance with the provisions applicable to political refugees.”

Credentials for Pavel Fabry to attend the First Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam, as a representative of the Evangelical church in Slovakia, signed by the bishop of the general church, dated 22 March 1948.

This is a photocopy of a photostatic copy, a statement written by the General Secretary and the Assistant General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, Geneva, dated 25 March 1948:

“To whom it may concern: This is to certify that Dr. Pavel FABRY, Czechoslovakian, born 14.1.1891[14 January] at Turčiansky Sv Martin, has been appointed as participant in the First General Assembly of the World Council of Churches, to be held in Amsterdam, Holland, from August 22nd to September 4th 1948.

We shall appreciate any courtesy on the part of Dutch and other consular authorities shown to participants in order to facilitate their coming to Amsterdam.”

From what I am able to translate, these next two documents seem to be asking Pavel to ‘voluntarily’ give up a lot of money or else, dated 1 March and 1 April 1948:

Attacks against Pavel Fabry were made in the communist newspaper PRAVDA, all clippings are from 1948, one is dated by hand 26th of August:

From 4 October 1948, this letter was written to Olinka, who was a student in 1947 at St. George’s School, Clarens, Switzerland:

“[…]We had Czech visitors a few days ago, a Mr. and Mrs. Debnar [sp?] from Bratislava, and we were deeply distressed to hear from him that Mr. Fabry had been taken off to a camp. Very, very much sympathy to you all[…]”

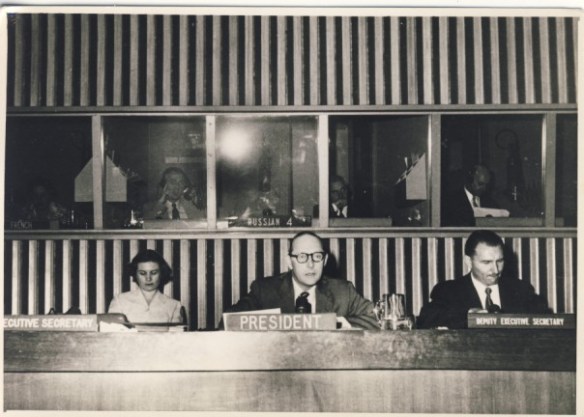

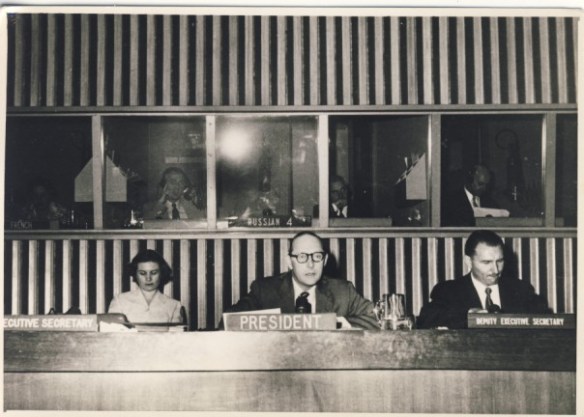

This is a letter from Vlado to Constantin Stavropoulos, written while he was on assignment for the United Nations in Indonesia, dated 10 October 1948. Vlado was asking for help in getting another assignment, so he could be closer to his family who needed him. I am appreciating more and more the emotional strain Vlado was under while writing this. Trygve Lie was the Secretary-General of the United Nations at this time.

“It’s more than a month now, that I received your cable that there is a possibility of an assigment for me in the Palestine commision, and that you will write me more about it – but I didn’t hear about the assignment anything since. The news which here and there trickle through from Paris or Geneva are not too good. They seem to indicate that I am not welcome there, not only as official, but not even as a visitor and that I should wander around or hide myself as a criminal. It looks as if the administration of my department /and from what they say, the administration of the whole organization as well/ would consider me as an outcast, who in addition to his other sins adds a really unforgivable one – that he behaves and expects treatment as if he would not be an outcast /at least that is what I understood from a letter written to my mother, that I should have voluntarily resigned a long time ago/. Excuse my bitterness – but I am simply not able to understand the attitude which is still taken against me – neither from the legal point of view of my rights and obligations under my existing contract, neither from a moral and ethical point of view which an organization representing such high aims to the outside must surely have towards itself. Sometimes I am [wondering], if the best would not be to let it come to a showdown and have it over once and for ever – it really is getting and obsession under which I have to live and to work all the time, specially since the UN employment means not only mine, but also my mothers and sisters /and maybe my fathers/ security and status. But exactly this consideration of my family’s dependence on it make me cautious and give me patience to try to get along without too much push. But, on the other hand, my cautiousness and fear to risk too much put me in the position of a beggar for favour, which is ipso facto a very bad one -/people who don’t care, or at least don’t show that they care, achieve things so much easier/- and which in addition I do not know how to act properly.[…]”

Further evidence comes from Washington state, U.S.A., from the Spokane Daily Chronicle 19 September 1961, “Crash Victim Known in City”:

“Vladimir Fabry, killed in the plane crash that claimed the life of Dag Hammarskjold yesterday in Northern Rhodesia, visited Spokane three years ago.

Fabry, U.S. legal adviser to the United Nations in the Congo is a close friend of Teckla M Carlson, N1727 Atlantic, and he and his sister, Olga, also a UN employee, were her house guests in 1958.

A travel agent, Mrs. Carlson first met Fabry in 1949 at Geneva after he had succeeded in having his father released from a concentration camp. The Spokane woman said they have exchanged letters since that time.”

By Marc Dragul - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Vaclav Havel, 17 November 1989, honoring Jan Opletal and others who died in the Prague protests of 1939. This was the start of the Velvet Revolution, which ended on 29 December 1989 with Vaclav Havel elected as President of Czechoslovakia, the end of 41 years of Communist rule.

Before continuing with the next documents and photos from 1990 to 2002, here is a copy of a letter dated 14 April 1948, from Dr. Ivan Kerno, who was Assistant to the Secretary-General Trygve Lie at the United Nations, and head of the legal department, giving his commendation of Vlado’s work. Dr. Kerno was instrumental in Vlado getting his position at the U.N., and was a good friend to the family.

Dr. Kerno’s son, Ivan, who was also a lawyer, would later help Vlado’s sister Olga in 1990, as they were both seeking restitution, and needed someone to investigate the status of their houses in Prague and Bratislava. This fax from Prague is addressed to Mr. Krno, dated 20 November 1990, from lawyer Dr. Jaroslav Sodomka. Dr. Sodomka writes that the Fabry house was “taken in 1951-52[the dates are handwritten over an area that looks whited-out] and later donated to the USSR (1955)[the date and parentheses are also handwritten over a whited-out area].”

“[…]As for Mrs. Burgett I shall also get the remaining extracts; here the problem is clear, be it under the small restitution law or under the rehabilitation law, the house will not be restituted as it became property of the USSR and the Czechoslovak government – probably the Ministry of Foreign Affairs – will have to provide the compensation.”

In response to this fax, Ivan Kerno writes to Sodomka, 7 December 1990:

“[…]please do not take any action with the authorities in connection with her house. She wants a restitution of her house, namely, to receive possession of the house, and is not interested in receiving a monetary compensation.

I have read in the New York Times this morning that the Czechoslovakian government has announced that it will compensate persons who have been politically persecuted or jailed under the former regime. This is a clear indication that the present government considers the actions of the former Communist government to have been illegal. It is also a definite precedent for the restitution of family homes which were illegally taken by the previous government and handed over to a foreign government.[…]”

This map shows our property in Bratislava, outlined in red:

From 3 January 1991, Sodomka once again writes to confirm that the house was confiscated in 1951, and donated to USSR in 1955:

“[…]As for your client Fabry, I think that it would be appropriate to address the demand for the restitution directly to the Chairman of the Slovak Government as it was the Slovak Government which has donated the house in 1955 to the USSR Government. This matter also is not touched by the small Restitution Law, the confiscation took place already in 1951 but I think that it would be appropriate to start to speak already now with the Slovak Government.[…]”

Olga Fabry returned to Czechoslovakia with her husband in June 1992, for the first time since her exile, to see the house. This next letter is dated 27 April 1992, and is addressed to Consul General Mr. Vladimir Michajlovic Polakov, Russian Consulate General, Bratislava:

“Dear Sir,

I would like to request an appointment with you on June 17th or 18th 1992 whichever would be convenient.

I plan to be in Bratislava at that time and would like to discuss with you matters pertaining to the villa that my parents built, where I was born and grew up and which now houses your Consulate.

I would greatly appreciate it if you would be kind enough to let me know in writing when I can see you. Thank you.

Sincerely,

Olga Burgett nee Fabry”

This is an undated letter from the Russian embassy in Bratislava(our house), the postal cancellation is hard to decipher but appears to be from June 5 1992, and there is a written note to “HOLD Away or on Vacation”. This may have arrived while Olga and her husband were already in Czechoslovakia – finding this waiting back home in New York, I can only imagine how she must have felt! This contradicts what Lawyer Sodomka told her, but it confirms Pavel’s testimony: the house was taken in 1948.

“Dear Mrs. Burgett,

With reference to your letter dated 27.04.1992 we inform you that at your request you have the opportunity to survey the villa while your stay in Bratislava. But we attract your attention to the fact that all the matters, pertaining to the right of property for the villa you should discuss with C.S.F.R. Foreign Office. Since 1948 the villa is the property of the Russian Federation and houses now Gen. cosulate[sic] of Russia.

Yours faithfully

Secretary of the Gen. consulate of Russia in Bratislava

S. Rakitin”

These photos were taken in June 1992, during Olga’s visit. The roses Maminka planted were still growing strong.

These two are undated, unmarked.

Lastly, the most recent photos I have, dated 25 July 2002, and the roses were still blooming.

When you search for images of the “Russian Embassy Bratislava”, you see the roses have all been removed now, and there is a new tiered fountain, but if you can ignore the flag of Russia and the gilded emblem of the federation hanging off the balustrade, it still looks like our house!

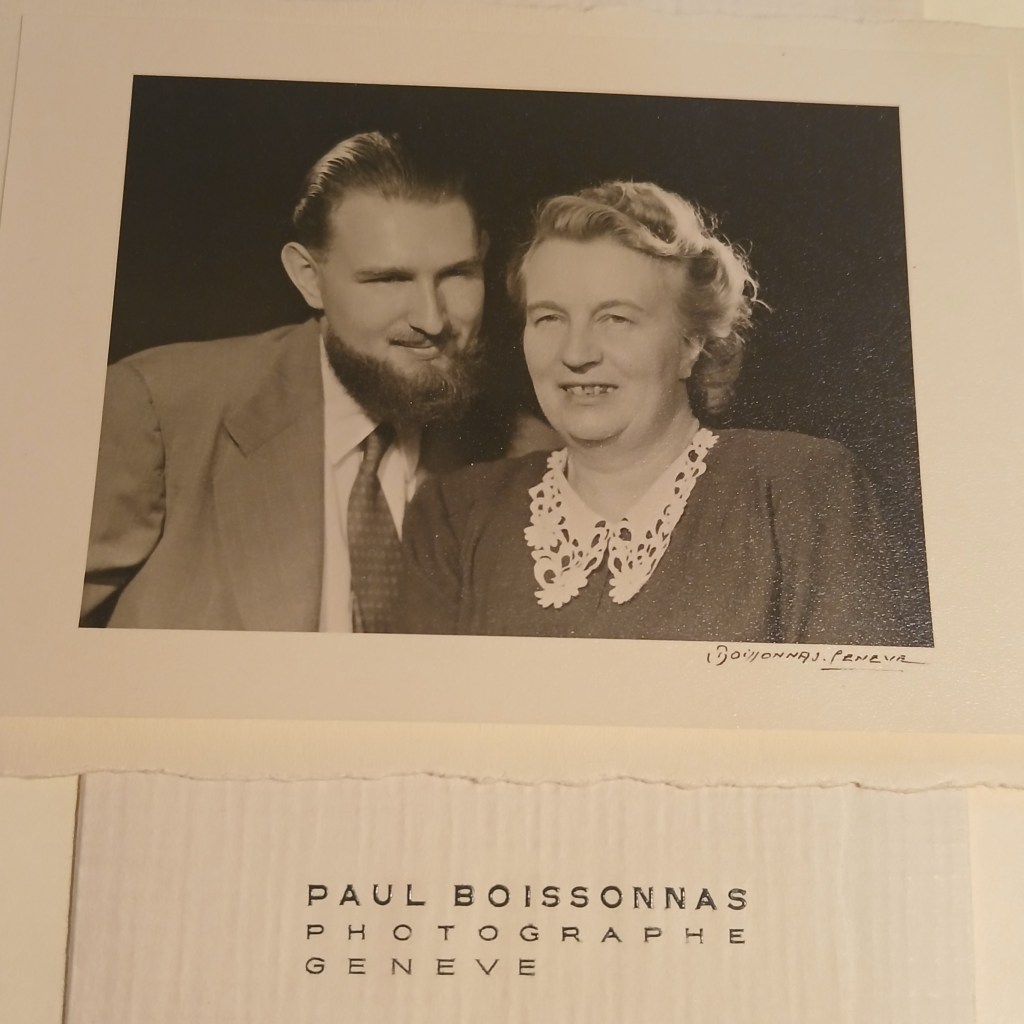

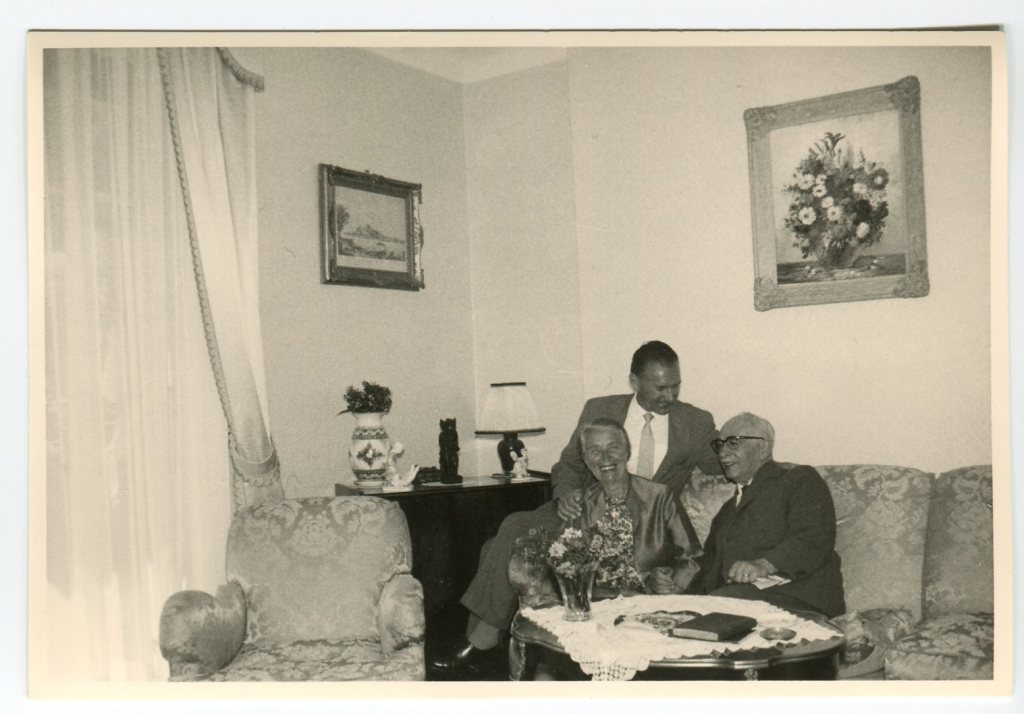

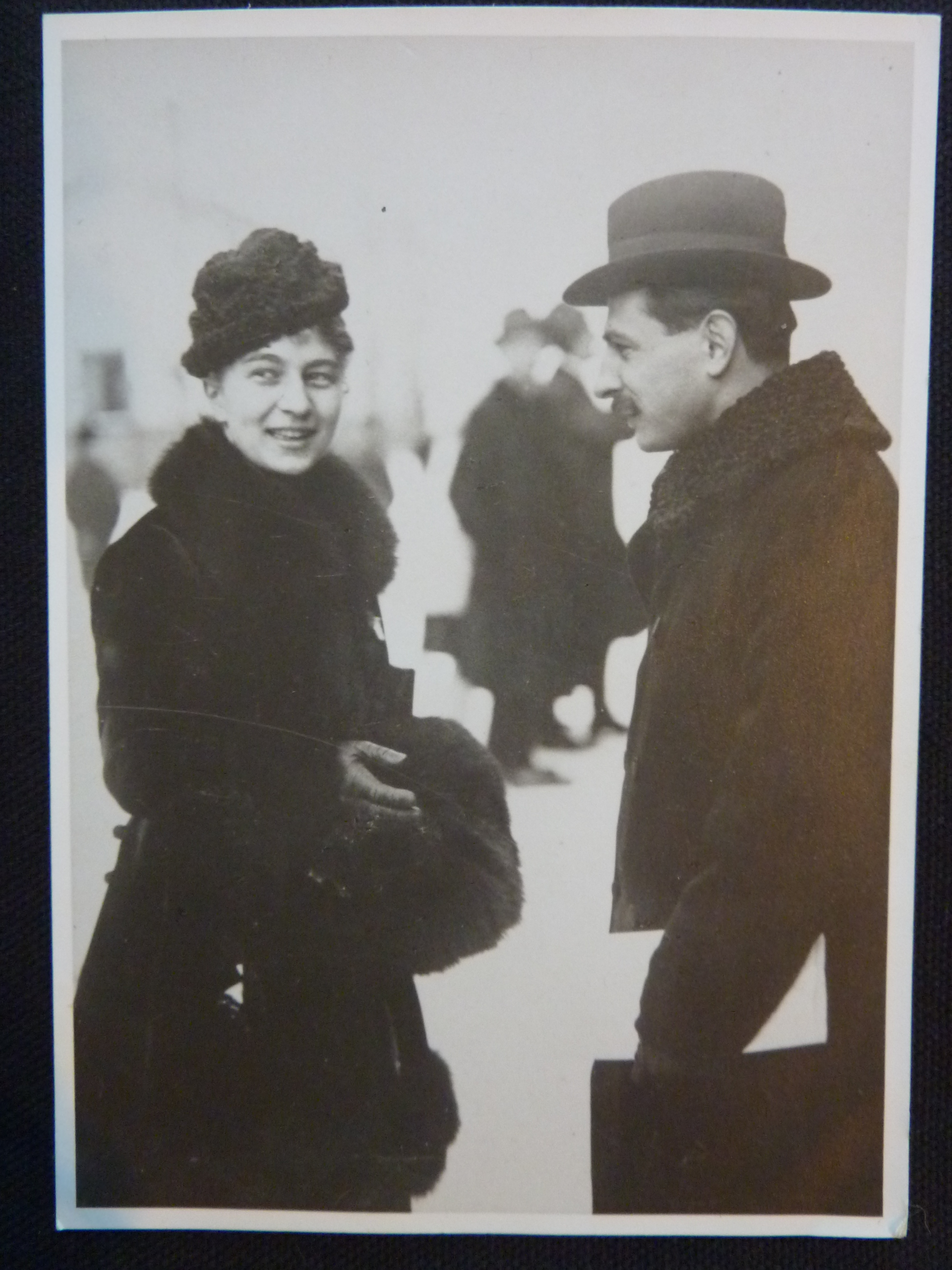

And now, because love is the reason I tell this story for my family, I leave you with my favorite photos of Pavel and Olga Fabry, who did so much good out of love!

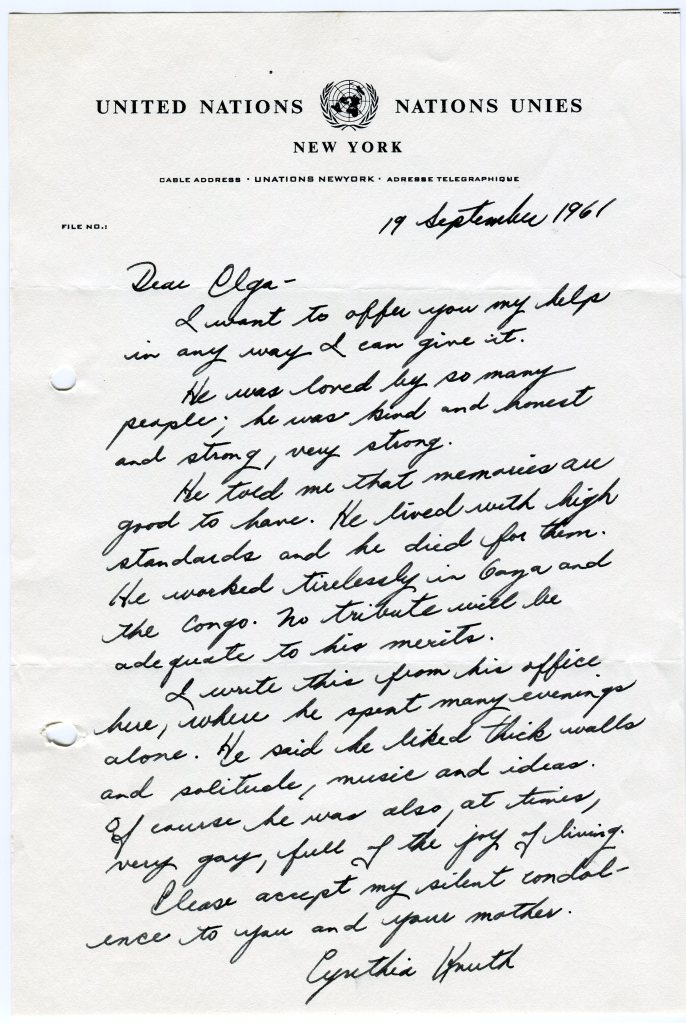

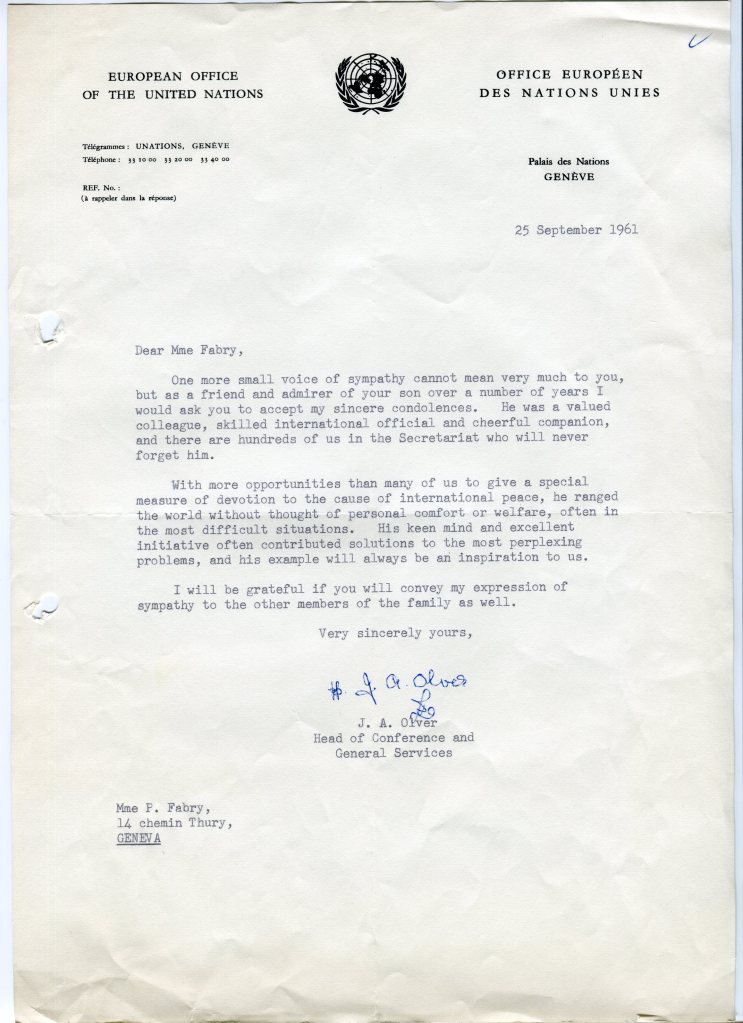

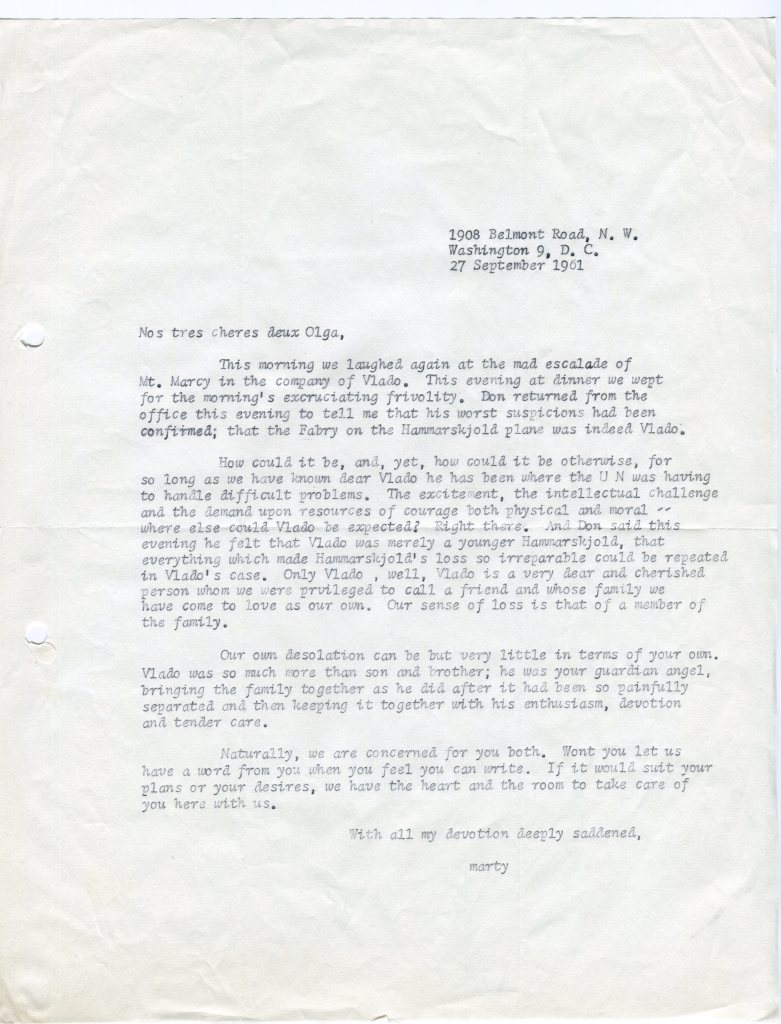

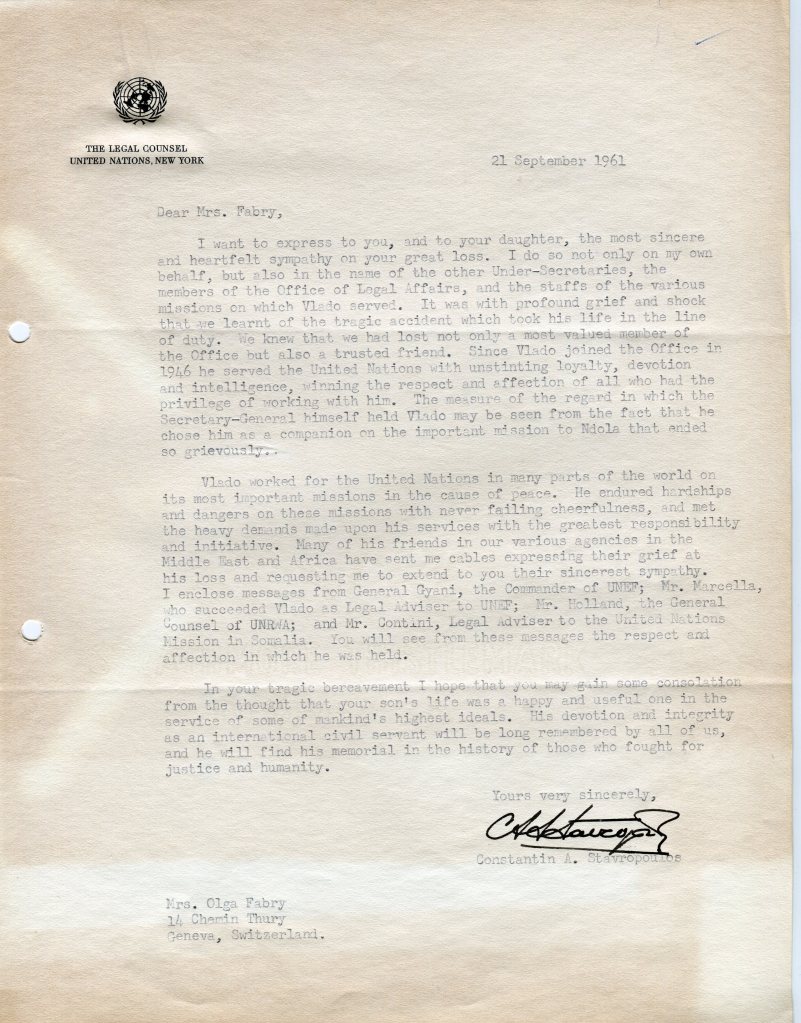

In memory of the 16 who died in Ndola, here is some of the collection from my mother-in-law, Olga Fabry, who carefully saved all the documents and mementos I share here. Vlado was only 40 years old when he died, a man who was very much loved by his family and friends, and my thoughts are with all the relatives around the world who remember their family on this day. The struggle against racism and white supremacy continues for us, let us not forget their example of courage to resist, and to fight for justice.

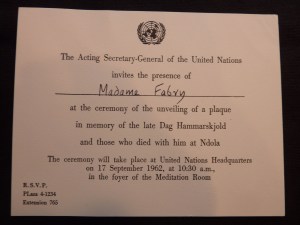

Program from the first wreath laying ceremony at UN Headquarters, one year after the crash, 17 September 1962:

Invitation from Acting Secretary-General, U Thant, to Madame Fabry:

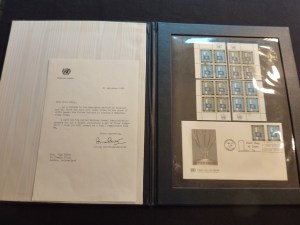

Letter and commemorative UN stamps from U Thant to Olga Fabry:

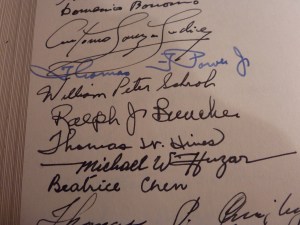

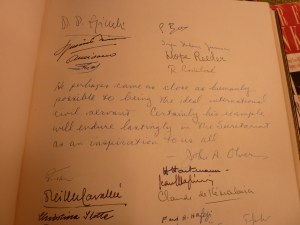

Signatures from UN staff were collected from all over the world to fill this two-volume set of books in memory of Vladimir Fabry:

Signatures from UN Headquarters in New York include Ralph Bunche, and his wife Ruth:

Signatures from Geneva Headquarters and a message from John A. Olver:

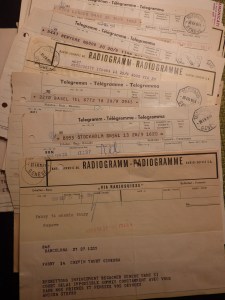

Telegrams from friends in every country:

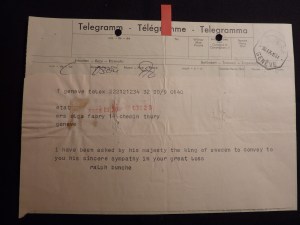

Among them, a message of sympathy from the King of Sweden relayed through Ralph Bunche:

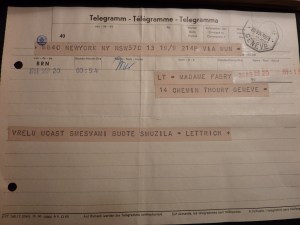

And a cable from Jozef Lettrich:

UN cables express the loss of a dear friend and highly valued colleague:

Newspaper clippings from 1961 and 1962, the first one with a photo of Olga Fabry and her mother at the funeral in Geneva, Switzerland:

The investigation will coming up for review in the General Assembly, and for those who think we should give up and be quiet about it already after all these years, Dag Hammarskjold said it best: “Never, “for the sake of peace and quiet,” deny your own experience or convictions.”

Couldn’t wait to share the treasure I found this summer, film footage of Vlado with his family in Switzerland. It may not be the best home movie ever made, but it gives me a lot of happiness to see these charming people all come to life, and to see Vlado skiing.

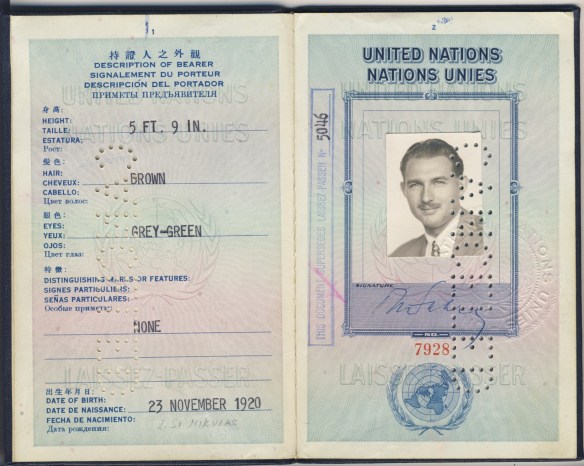

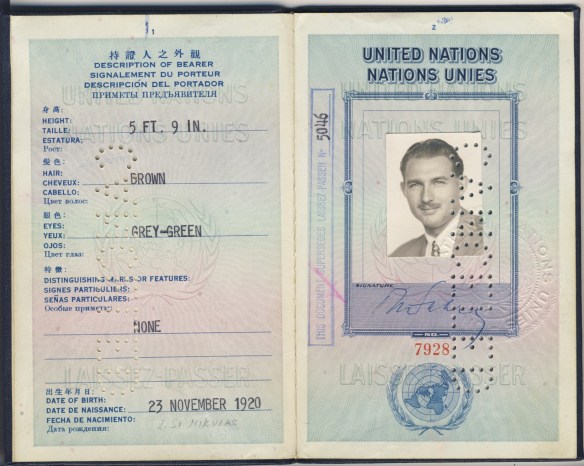

From 1949 to 1951, Vlado was working for the United Nations in Indonesia, during the time of independence from the Dutch. Due to the complications of being a political exile from Czechoslovakia, Vlado had only a temporary passport – until October 1952, when he finally received his UN Laissez-Passer. Here is one alternative ID, a ‘Tourist Introduction Card’ from the Government of India:

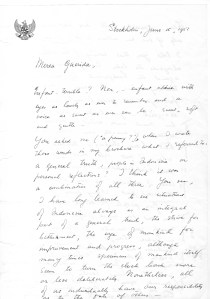

Sumitro Djojohadikusumo (not to be confused with General Sumitro)was the only Indonesian with a doctorate in economics after independence in 1949, and had been Deputy Head of the Indonesian delegation to the UN Security Council, so he and Vlado were colleagues. While going through the 1951 box of papers again, I found two letters – one for Vlado’s sister and one for his mother, with Indonesian letterhead, handwritten and signed by Sumitro. It shouldn’t surprise me that Sumitro came to be friends with Vlado and his family, and that their example of kindness moved him to open his heart to others, but I had no idea how fond he was of Vlado’s sister!

Stockholm, June 15, 1951

Merea Guerida,

Enfant-terrible? Non, – enfant cherie with eyes as lovely as ever to remember and a voice as sweet as ever can be: sweet, soft and gentle –

You asked me (“a penny?”), when I wrote those words in my brochure what I referred to: a general truth, people in Indonesia or personal reflections? I think it was a combination of all three. You see, I have long learned to see situations of Indonesia always as an integral part of a general trend, the strive for betterment, the urge of mankind for improvement and progress, although many times specimens of mankind itself seem to turn the clock back more or less deliberately. Nonetheless, all of us individually have our responsibility as to the fate of others —

Then, general truth has particular significance only if one can attach to it, personal reflections. I told you that evening (la ultima noche) alongside the lake looking towards Geneva, against the background of mountains and twinkling stars, the lesson I learned from you and your parents. I do not exaggerate – your brother I think can tell you how much under control, reserved and reticent I usually am when meeting people – but how strikingly touched I was, when I met with such generous welcome and kindheartedness from all of you. And I compared my own attitude in the recent past, shying away from gatherings and from people (- though many of them were out for quick profits and complaints, maybe you remember I told you.) My time in Geneve taught me that only through kindness and understanding can you make people understand. Needless to say that my time in Geneva is inextricably connected with the shining, lovely personality of Olga Irene. (remember again, I do not exaggerate, wherever you are concerned.) Now, Carisima[sp?], till next time, for I hope you will continue writing me from time to time, for never shall I forget….

Ever Yours,

Sumitro

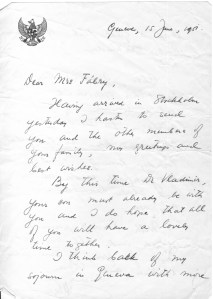

Here is the letter he wrote to Mrs. Fabry, with an apology regarding Vlado’s sister:

Dear Mrs Fabry,

Having arrived in Stockholm yesterday I hasten to send you and the other members of your family, my greetings and best wishes. By this time Dr Vladimir, your son must already be with you and I do hope that all of you will have a lovely time together. I think back of my sojourn in Geneva with more than a great deal of pleasure and gratitude towards you all.

Also, I would like to take this opportunity to extend to you my profound apologies for the fact that Olga came home so late that Monday-evening. I have no justifiable excuse really and should have been wiser at my age — With kindest personal regards and all my best wishes for you, Dr Pavel Fabry, Vladimir and Olga,

Sincerely yours,

Sumitro

I wonder if Sumitro got a scolding at the door from Maminka? He didn’t sound very sorry about coming home late in his letter to Olga!

“Sometimes the key arrives long before the lock. Sometimes a story falls in your lap.”

–Rebecca Solnit “The Faraway Nearby”

Though it is clear that I love the Fabry family very much, what might be difficult to believe is that I was not accepted by my mother-in-law, Olinka, and that I only met her once before she died. As much as I wanted to know her, there just wasn’t enough time, and I was very sad about that. So, you can understand how these papers have been a gift to me, to be able to get to know who Olinka was, to understand why she was difficult and the hell she had been through – I think of her with compassion and forgiveness.

Besides being a great cook(see photo above), one of the qualities I admire most about her was her skill at many languages – she was as gifted as her brother Vlado.

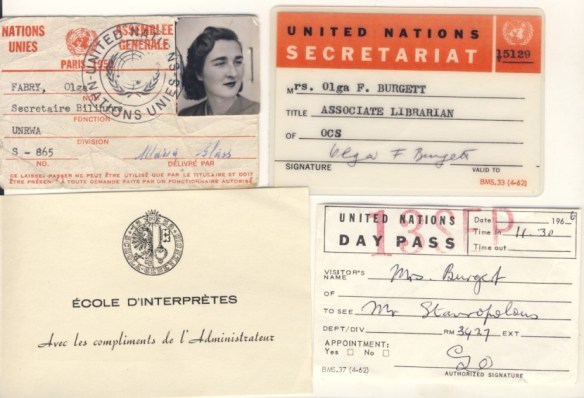

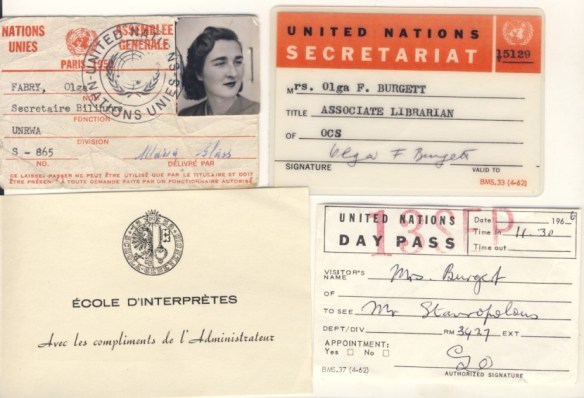

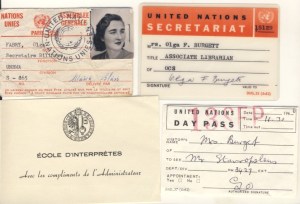

Here are a few pieces of ephemera from Olinka’s career:

It would have been easy for her to translate this document from the Prison de Saint Antione in Geneva(which is now the Palais de Justice), dated 1949, but it is not so easy for me. Who was in the prison? And why? Was it her father, Pavel? I am posting this here in hopes that Slovak readers will want to contribute a translation, if only to ease my curiosity. Please help!

(click image to enlarge)

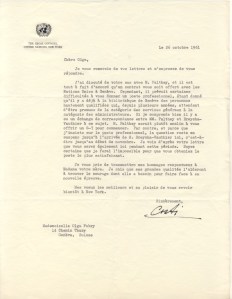

Desperate times call for desperate measures, and here is a letter of great desperation written by Vlado’s sister, Olga Fabry – who was still a stateless political refugee at the time of his death – asking Constantin Stavropoulos to help her obtain a professional position at the U. N. Library in Geneva. With both her father and her brother gone, she suddenly had to financially support her mother and herself, and that meant being bold and asking every important person she knew for help. This letter was translated from French:

Oct. 10, 1961

Cher Costi,

Allow me to thank you again for your presence at Vlado’s funeral and for your lovely speech to the church. Your presence was a great comfort to my mother so painfully struck by the cruel loss of her beloved son.

Maman has been admirable until now, but the much dreaded reaction unfortunately has already started to manifest itself. It’s a bit too much for her and for me, especially since Christmas, when Papa died, we had only Vladko for our support. Vladko was our support, notre soutient, our everything, in this world in which we are already deprived of homeland and family. Now we have also lost Vladko, so tragically, so brutally and it seems the ravine of misery and despair appears to engulf us slowly…. Mother is even more saddened and upset since she was always so opposed to his mission in Congo, especially so soon after the death of my father.

Even in New York in the Spring, you were out, I think, she asked M. Schachter could Vladko return as soon as possible. She has been very worried and unhappy ever since Vladko has been in Congo, as if she had a presentiment… She showed me now the copies of letters she wrote to you and Mr. Schachter when Vladko was sent to Congo; he knew nothing of these letter, but she had felt something, and she wanted to do everything for him to return… alas, he left his life there.

Now we have, in our present so heavy, such desperation to take care of our future.

After talks with the Head of Naturalization in Geneva, I obtained a promise of Swiss naturalization on the condition of having employment at the United Nations in Geneva.

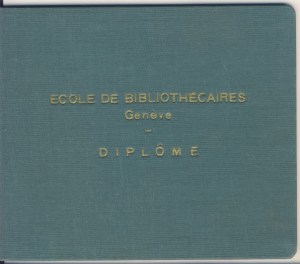

I went to see the director of the Library of the United Nations in Geneva, Dr. Breycha Vauthier, who told me of a professional vacancy in the library. He told me he would like very much that I take this position, because I have already worked in the Library of the United Nations in Geneva, I know the languages and that New York always sends someone who is not proficient, who does not know the languages and of which one wants to get rid of.

As I have already worked temporarily on several occasion in the Library, I have already a good experience and thorough knowledge of the functioning of the U.N. Library in Geneva. I’ve even done my diploma work. In addition, my experience in the United States where I am “Head Librarian”, my development from below can only speak in favor of my professional competence. In New York I hold a professional position and my salary is equivalent to that of P II in the United Nations.